AI music: beyond the buzzword

Are robots taking over? A conversation with artists, experts, and industry insiders about what the tech really means and how it's being used

AI is everywhere right now.

The term’s popularity on Google exploded in November 2022 with the launch of Chat GPT, the AI language model which almost immediately went viral with users sharing their sometimes useful, sometimes hilarious experiences with the technology.

The search interest for AI exploded when Chat GPT hit social media

People jumped to share their results when providing the AI with 'interesting' queries

@breakstuffpod AI cover | AI music: Freddie Mercury sings Hey Jude (The Beatles) By AI-Singer #ai #aimusic #music #musica #artificialintelligence #artificialintelligenceart #aiart #musician #musictok #aicover #aicoversongs #singing #singer #cover #coversong #coversongs #inteligenciaartificial #ia #audio #audios #audiosparatiktok #audioviral #audiosforedits #viralaudio #viralaudios #coverband #freddymercury #freddiemercury #rock #rockmusic #rocknroll #rockandroll #fyp #beatles #thebeatles #paulmccartney #heyjude #ballad #60s #1960s #60smusic #60sfashion #70s #1970s #1970saesthetic #1970sfashion #1960smusic #1960saesthetic #throwback #throwbacksongs #sixties #seventies #aigenerated #aigeneratedmusic #audiooriginal #originalsound #originalmusic #vintage #vintagevibes #vintagestyle #poprock #johnlennon #musicproducer #musicproduction #musicproducers #djs #djremix #remixchallenge #remix #dj #playlist #mixtape #trending #trendingtiktok #trendy #trends #trendviral #mix #love #lovestory #lovesong #romantic #sadsong #emotional #couples #soundtrack

♬ HEY FRED - Break Stuff

Over a million users tried out OpenAI’s then latest model within five days of its launch.

When Google themselves announced at the start of this year they had developed a similar system which could create music instead of text, ‘AI Music’ almost immediately reached peak interest on their search engine - the concept entering many of our minds for the first time.

Fast forward to now, and elder statesmen of pop music are lining up one after another to proclaim the AI doomsday that is facing the music industry, while a select group of others such as David Guetta champion the tech as ‘the future of music’.

Meanwhile AI voice covers are flooding social media, particularly on TikTok, where you can hear Freddie Mercury sing ‘Hey Jude’, or even Barack Obama take on ‘Let it Go’.

There was also much confusion recently when Paul McCartney announced a final Beatles song would be released with the help of artificial intelligence (it was actually used to help isolate the vocals of a John Lennon demo, rather than create anything original).

It seems like AI and its use in music has at once become both sensational and polarising. It is the latest ‘buzzword’ dominating conversation, both inside music but also outside at times.

“There's a reason there are tech buzzwords because once in a while they're real…It's going to change everyone's life. It's going to be like electricity.”

Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky talking recently to Yahoo News

“25 years ago, everyone was talking about the internet or cyber. What does that mean? Nothing. Is it digital? Is it mobile? So when people say AI, they similarly use in that way.” - Cliff Fluet

Cliff generated this picture of himself with the help of AI

Cliff generated this picture of himself with the help of AI

Cliff Fluet has been at the forefront of the vast changes that have happened in the music industry since the internet age. Working originally as an in-house counsel for Warner Music UK in 1997, Cliff was part of some of the first ‘extraordinary’ conversations with companies like Apple, Amazon, and Napster.

Since then, he has been a leading figure in the digital music industry as a leading adviser and lawyer, working with start-ups who are at the cutting edge of music and technology.

Cliff believes AI music has become a catch-all phrase that doesn't reflect the different ways artificial intelligence is used.

“There is a particular strand of AI music, which we call generative music, where people train a model with music and information, and then it produces another sound. Everyone is lumping it in with all sorts of other AI and music. There's AI Lyrics and AI Voices, Spotify playlists work through AI algorithms.

“So when people use those super wide generic phrases like AI Music, you've got to be actually really, really clear what you're talking about.”

The trustee of multiple music charities also questioned how ‘new’ the use of certain forms of AI is, despite its apparent sudden explosion onto the scene, as well as how ‘new’ the issues are it poses the industry.

“Generative AI is not that new. I first started working with a company called JukeDeck in 2013, where you could press a button and it would create music out of thin air.

“The recording industry has always had this very, strange relationship with technology. It seems think it’s from some other galaxy or from some other dimension. The recorded music industry was invented by technology.

“If Bowie was alive, would he be working with technology? Absolutely. This is all arid nonsense. It’s what we call a bowel panic - people saying it’s the death of artists.”

Earlier this year, the government scrapped controversial plans to allow a copyright exception for text and data mining, which would have allowed companies to use copyrighted music catalogues as data to train their AI models.

UK Music Chief Executive, Jamie Njoku-Goodwin said the plans would have ‘paved the way for music laundering and opened up our brilliant creators and rights holders to gross exploitation.’

When used in the correct way however, this exact process can actually help musicians be paid for use of their work.

Cliff said: “The biggest problem that we have in the music industry is getting artists paid in the digital world, it still seems to be beyond what's capable. In a lot of things like metadata and transcription, AI could have a huge impact on the solution, helping people get paid and ensuring proper attribution.”

He believes artists and record labels need to embrace the technology and find ways to licence it, rather than hope they can make it go away.

“The industry isn't smart enough, thoughtful enough, aware enough that it needs to come up with innovative licensing. I think the answer is something along the lines of the Grimes type model.”

(Canadian musician Grimes announced software earlier this year that lets you convert vocals into her voice, which can be released commercially as long as royalties are split 50/50)

“The first song that ever had a popular sample in it was Rapper's Delight, which took samples from Nile Rogers. He could have said no and shut it down, instead he okayed it, but wanted half the money. He ends up with a tonne more money.

“When the music industry doesn't licence, it makes no money…The idea that AI voice cloning is going away is just nonsense. I think it's going to be a big thing.”

While AI voice cloning is still most at home on social media and with home users, a glimpse of a possible future emerged when David Guetta recently released a song with artificially generated Eminem vocals.

The French DJ said he would ‘obviously’ not release the song commercially, but it hasn’t stopped some from trying to make money through the technology in other ways.

There are a number of ‘freemium’ sites that allow users to upload their own tracks which the site then converts, so they don't have to build their own model and manually do this.

Many TikTok accounts that post ‘voice cloning’ videos put links to these sites - such as Voicify, VoiceDub, and previously Uberduck.

These companies often have their own profiles too which share covers made using their software.

Posts like this are extremely popular on the platform

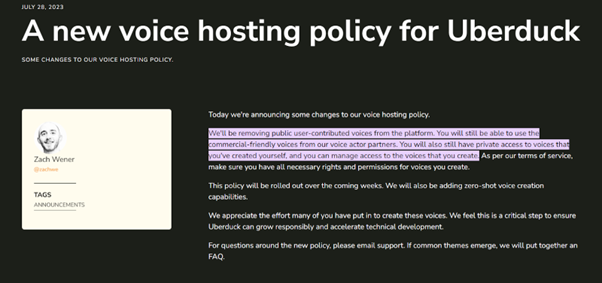

The latter of these has recently removed almost all copyrighted voice models, such as famous musicians or actors, even if they were generated by users themselves.

Uberduck faced copyright claims from voice actors Jim Cummings and Tara Strong, leading them to announce they are focusing on ‘commercial friendly’ voices.

It’s still incredibly easy to generate these kind of covers on other platforms however.

For £8.99 a month, Voicify will let you do 25 voice ‘conversions’ a month - and it is as simple as picking a voice and pasting in a YouTube link.

It’s not entirely clear whether the company uses a licensing model (after declining to comment), but it seems they are trying to distance themselves from any possible infringement.

The Terms of Use state: “It is important to clarify that these models are completely artificial creations…They do not incorporate or utilize any proprietary recordings, performances, or unique voice samples of these public figures.”

Voicify further ‘prohibit’ users from infringing intellectual property rights, and also state they must ‘indemnify’ the company from any claims resulting from its use.

Uberduck's announcement of their changes after the copyright claims

Uberduck's announcement of their changes after the copyright claims

"The novelty effect will wear off...but it's going to start getting embedded in all the technologies that we're using"

Dr Nick Bryan-Kinns also leads international partnerships for the UK Research and Innovation Centre’s leading programme in AI Music.

Dr Nick Bryan-Kinns also leads international partnerships for the UK Research and Innovation Centre’s leading programme in AI Music.

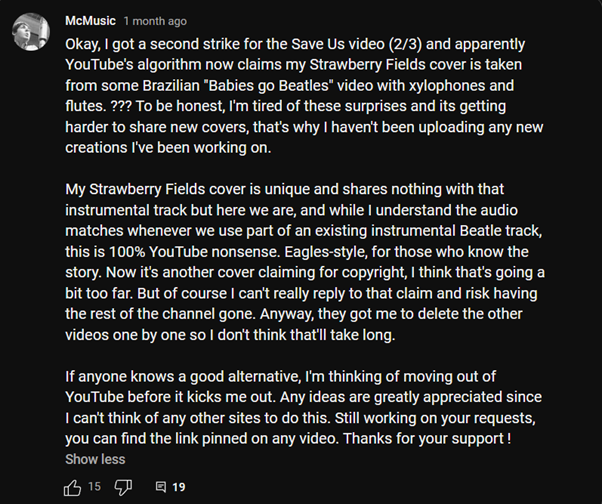

The artist talks about the YouTube copyright strikes on the channel. They did not respond to a request for comment.

The artist talks about the YouTube copyright strikes on the channel. They did not respond to a request for comment.

Nick Bryan-Kinns is Professor of Interactive Design at Queen Mary University of London.

He points out the difficulty with rights, especially as novel issues are encountered with the technology.

“The question is, were they using material that was copyright free to train the model, and if not, then they should be paying some licensing fee to use the material.

“If you say - I can make your voice sound like Freddie Mercury, and I've trained this model using the whole Queen back catalogue, that's clearly violating Fair Use copyright.

“If somebody was a very good mimic however, and went ahead and trained a model themselves that sounded like Freddie Mercury, is that then a problem? Should they be paying any money to his estate? Or is that just their artistic performance as somebody who sounds like Freddie Mercury?”

The reverse can also be applied as well.

A good mimic, with an AI voice model applied on top, can achieve even more impressive results than simply applying it over an existing song or vocal track from a completely different artist.

Some people are already doing this. The ‘McMusic’ YouTube account belongs to a professional singer and musician who uses their skill to create freakishly impressive results based on Paul McCartney.

McMusic's only remaining video, which is a full self-made recreation of a Beatles outtake, with AI used to enhance the vocals.

They offer custom commissions, but have been left with only one video left on the channel after having to delete the rest after receiving multiple ‘strikes’ from YouTube.

Using models based directly on artists can be much easier to shut down, despite the amount of work that still needs to be done by creators such as McMusic.

Lawyer Cliff Fluet explains: “If you build a machine that has been trained on the works of the Beatles, or trained on the voice of Paul McCartney, you are back to your fundamentals. Is there a copy? Are you committed to breach of one of the restricted acts? Probably.

“You're going to use a magic bullet of personality rights, image rights, trademarks, voice training, music training. So if they did want to shut it down they could. These kind of voice clone mash ups, Drake singing the Weekend type stuff, they are all magically disappearing from Spotify.”

The fact that people are using the technology in this way, which researchers such as Prof. Bryan-Kinns have worked on for the last five years, is something he says they did not anticipate.

It utilises a similar form of ‘deep learning’ that language models such as Chat GPT use, except it is trained on sound.

“This one is generating voice, so you will train a deep learning model on a lot of recordings of somebody's voice. And then you match that up to say, the lyrics, or the words that they were saying, as the training input.

“Then you can ask it to generate either new speech from text. So based on what you've taught it, or you can just use it to transpose from one style to another, or one person's voice to another.

“What’s happening now is people are starting to use existing models, so you have a base model of, say, a male person from England, and then you customise it with your own voice. That way you need much less training.”

The researcher feels that although there will be a decline in interest, the AI behind this vocal cloning is going to have a big impact both in music, but in speech and voice technology more widely.

“The sort of novelty effect of training your own voice, singing like somebody else, that'll wear off. But it's going to start getting embedded in all the technologies that we're using…fairly soon in Zoom for instance, you’ll be able to have real time translation of my voice into a different language. It'll be a straightforward thing to do.

“The TikTok mashups seem like a flash in the pan. But it is a different kind of genre that's already emerged due to AI. I think other different styles or genres will start to emerge, and you can't really predict more about that, because it's going to be something that somehow has a feel to it or something that resonates with a certain segment of society - that really makes them want to listen to it more.”

This changing of one voice to another is also known as 'Timbre Transfer", and is not only limited to voices. It can also be used to make instruments sound like other instruments, or voices like instruments.

Musician Yotam Mann has worked with grammy award-winning artists, and is interested in how technology can be used in music. He demonstrates 'Timbre Transfer' happening in real time using an AI model trained on Mozart's symphonies (as far back as 2019)

Dr Collins was recently involved in a study which showed musical experts consistently rated AI generated pieces lower than human composed pieces when they weren't told which was which

Dr Collins was recently involved in a study which showed musical experts consistently rated AI generated pieces lower than human composed pieces when they weren't told which was which

“For Damon Albarn and Blur, there’s probably moments where it sounds very cockney, and so, if you put Kurt Cobain on top of that, it doesn't necessarily change the way certain vowels are used. It still sounds cockney.”

Dr Tom Collins, Assistant Professor in Music Technology at the University of York, tries to imagine how the voice technology could be used to convert accents too, something it can be said to sometimes struggle with at the moment.

“I think it could become part of a creative workflow where there's some middle person who's still there, like a human in the loop at that stage that kind of glues these two things together. Or, you have to redesign the way that the algorithm is working.”

Dr Collins however, uses artificial intelligence in music in quite a different way himself, having represented Britain along with his spouse in the first annual AI Song Contest.

Inspired by Eurovision, the competition aims to promote ‘the possibilities of human-AI co-creativity’, and held its first competition in 2021.

“I made it relatively quickly with my spouse, because I had been working with Imogen Heap on the song, but when lock down came in while we were trying to finish it off, it didn't happen.

“So we had AI generated starting materials, and we had to do it within a matter of days before the deadline. It was around 20 to 30 melodies, baselines, drum beats, and chord sequences that had been generated by a Markov model. The lyrics come from an AI Lyric generator site.

“They provided us with something like 200 previous Eurovision entries in MIDI format - so it was very tied to the competition.”

To break it down, the MIDI data (which is essentially instructions for computer software to know what notes are played, how loudly or quietly and so forth) was used to train an AI model.

This model was then used to generate the 30x 4-bar extracts of different components of the song such as bass or melody, which Dr Collins then picked the best of to incorporate into the song.

It’s easy to think this would just lead to repetition of other Eurovision songs, but when trained with a large dataset, these generations can be new combinations of notes or beats.

Dr Collins gave a simplified explanation of this.

If a model is trained on all the lyrics of the Beatles for instance, when the word ‘Yellow’ is generated, more often than not the word ‘Submarine’ will follow due to the model trying to predict what word should come next.

Occasionally however, the word ‘and’ could be generated, due to appearing after ‘Yellow’ in another Beatles track. When the model then tries to predict the word after ‘and’, there are a range of different potential word choices, and over the course of many generations this can lead to '"new" music in the style of a corpus of existing music.'

See the Pen Markov Chain Lyrics Generator (Magical Mystery) by George Litchfield (@George-Litchfield) on CodePen.

There are different types of Markov model the lecturer explains, and more complex forms of deep learning models operate differently, but he says he uses an assignment related to this explanation, where each student brings a set of Beatles lyrics, to introduce them to the subject.

He feels using generative AI in this sense can help people develop new ideas, rather than being a tool for developing existing ones.

“The exciting thing is when it kind of puts you in places that you wouldn't have got to on your own, I think we've arrived in a place where we can use this technology to access parts of creative space that we couldn't before.

“But if someone's got quite a strong idea of what they want already, and they don't have writer’s block, or a fear of the blank canvas, then they can find it quite difficult to get on with the AI.”

Dr Collins had access to a studio and a larger team for the latest entry he was involved in

‘Getting on’ with AI is even more important when a musician is performing alongside it.

Dr Oded Ben-Tal, a composer and senior lecturer at Kingston University, has been working on a form of ‘musical dialogue’ between performer and AI through live improvisation.

The researcher feels there is a natural fear of new technology

The researcher feels there is a natural fear of new technology

It led to him collaborating with Professor David Dolan, an world-leading expert in more ‘traditional’ forms of improvisation, who was surprised by the composer's ideas about machines.

Dr Ben-Tal said: “He told me that he came into the studio session with the aim of proving that I'm talking nonsense, that this can't be done.

“He was surprised that he heard at least moments of dialogue with the computer, that got him really excited and intrigued, and we both heard something interesting happening and wanted to continue working on it.”

The pair held a concert earlier this year, which was the first ever duo improvisation in the UK between AI and a human in real-time.

A short clip from the performance, which the composer called: 'The Odd Couple'. You can also hear his system take the form of a guitar and other ambient noises in another improvisation with Dr Dolan.

Moment to moment decisions are made by the system, but some controls such as volume mixing are still controlled by Dr Ben-Tal.

Although the system is still ‘on rails’ to some degree, in the sense that someone couldn’t just walk up and play a random instrument to the system and expect a quality result - the composer believes this could definitely be possible in the future.

He also strongly disagrees with the idea that using AI is ‘less creative’ in any way.

“We tend to think that we are the only creative creatures in the whole universe. We're very reluctant to give credit for creativity to anything else. So the moment someone demonstrates a system that can do something which we thought was creative five years ago, we call it a ‘technique’ instead.

“My approach is that creativity is actually a lot of different things. It's not just about staring into the wall, and suddenly having inspiration, it’s about thinking, developing, and working out new things.

“I see no reason why computers cannot be integrated into this creative process, and contribute something they can be made to to be good at.”

“It doesn't really take over anything, it’s like a stepping stone"

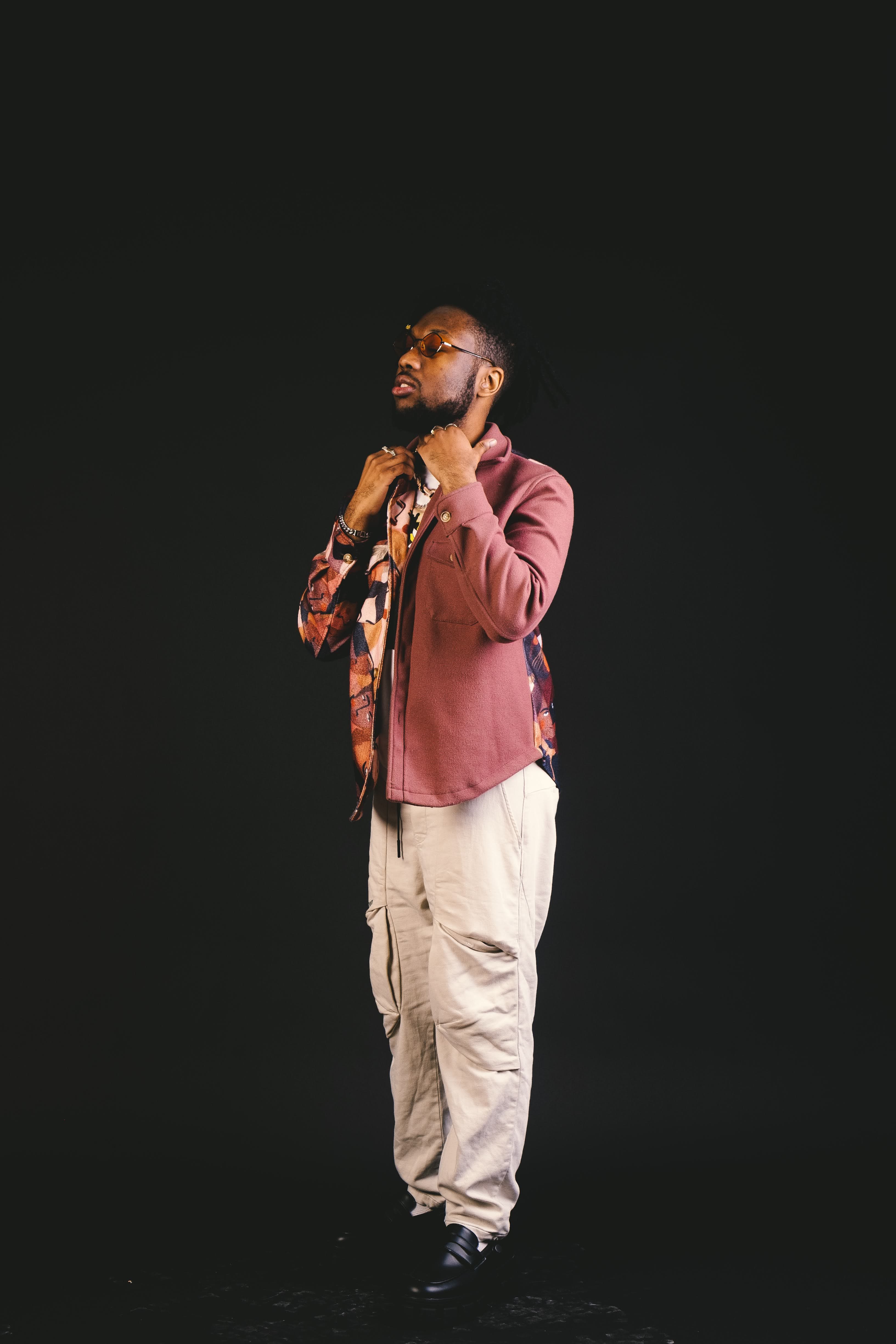

Tee Peters, a jazz rap artist from London, echoes the composer’s thoughts.

“If I use Chat GPT to give me a starting line for my song, they'll say that creativity is over. But you have to remember if I go ahead and look at a random book that's next to me, and say I read the first line and I use that as my inspiration, is that not creativity?

“I think people’s definition is just all wrong. It isn’t just about generating something out of thin air.”

Originally working as a videographer while pursuing music as a hobby, Tee made the switch in 2018 after losing all his equipment when the Lil Pump concert he was filming was hit by a tear gas attack.

“I went home and said I'm just going to do music, because for some reason I didn’t really care about my equipment. I probably would’ve cared more if I lost my microphone. I realised this really wasn’t my calling.”

The 25-year old uses AI for assistance as a creative tool, including when in the production process of a track.

“It doesn't really take over anything, it’s like a stepping stone to some of the things that I'll be doing with music.

“So for example, I'll be making like a demo, and if I'm not in a good position when I record my vocals, so if there’s loads of background noise or I had to sing very quietly and and it wasn't the best recording, without AI, I’d have to mix the demo myself, and have to go through a long process of making a chain of effects and fine tuning them to make my song sound good.

“That would take me a long time. It could be 30 minutes if I don't care, or for some people, it can take them days and weeks. I have other things to do and I'm trying to make a demo - nobody has that time to spend right now.

“So what I would do is open a plugin which uses AI, it asks you for certain things and has a vocal assistant button, and when you play it, it will basically do all of that stuff that I said about in ten seconds.”

A recent survey from charity Youth Music showed that generally as respondent’s age increased, the likelihood of them being willing to use AI creatively either now or in the future decreased.

Tee himself is also the programme manager of Wired4Music, a charity which offers support and opportunities in music for 16-25 year olds in London.

He believes the technology can make music more accessible for those with dyslexia or who aren’t musically trained.

“It can 100% help with accessibility. Some people might struggle with things like writing down music or writing lyrics. If you're a musician, and you're by yourself, you don't have a team to help you.”

The artist from Peckham feels criticism from those outside music is especially unfair.

“It’s definitely ignorance. People who don't even make music or don’t even touch the microphone. It's hard not to be ignorant.

“But even some musicians say it, they have a personal opinion on it and think it's a cheat to make music in a certain way.”

Jon McClure, frontman of Reverend and the Makers, defended the use of AI as a creative tool in a recent Q&A

Alto Key, a UK indie artist who boasts over 1.5m followers and 30m likes on his musical TikTok account similarly uses AI tools in the production process.

He stresses however, that he hopes it continues being a tool rather than being used as a replacement by certain sectors of the music industry, as the technology becomes even more advanced.

“I think we're a long way off from AI being able to predict what people think sound good as it's subjective and forever changing.

“But even if it becomes technically possible, I disagree that AI should replace humans. It's important we protect the livelihoods of creatives. I think the world will become a sadder place if music is all auto-generated and mass produced without human intervention.”

Not everyone thinks this change will ever truly happen however.

Mark Christopher Lee is a veteran of the music industry.

He has been the lead singer and composer of indie band The Pocket Gods since 1998, and set up his own digital label ‘Nub Music’ in 2005.

Mark says he is more concerned with the impact the technology will have outside of music.

“AI in society is more scary than AI in music.

“I worry more about shop workers, and the people who are not so fortunate to have a gift where they can do music. They've got to do a job that could be taken away by machines. That's the scary bit.

“We've always used technology in music, and I see AI as an extension of that. I believe it's not anything to be too afraid about.”

The musician with 10 Guinness World Records, has managed to gain national media attention many times with his campaign for fairer streaming royalties.

Mark produced a 1000 song album with his band in 2022, made up of tracks which were all around the 30-second mark, to protest the amount Spotify pays artists.

The band earns about £0.002 per stream, which is only paid out if a listener plays a track for at least 30 seconds, which is what prompted the size of the tracks on the album.

Mark feels the conversation around AI has paved over other important discussions that are needed about the industry.

“AI is a distraction from the economic reality for artists today in terms of streaming revenue and touring, and the nightmare impact of Brexit on musicians.

“People have always had the fallback in the industry of being able to go on tour to make money that way, but you can’t now. They’re having to cancel tours because it’s just so expensive.

“I worry about the future of artists coming through.”

The Pocket God’s have experimented with AI, having released an ‘AI Version’ of their latest album alongside the ‘human one’, which was created by uploading their tracks into software which creates ‘new’ versions of the music you provide.

Mark feels however that the technology will never be able to replace musicians completely, because it will never be able to connect with people in the same way.

“AI doesn't have a soul. It doesn't have that creative spark that musicians and songwriters have. You're never going to be able to recreate them because their music comes out of a melting pot of who they were, where they were from, the culture, the time.

“The issue is at the moment AI isn’t creating something new and unique. Which I believe is a human thing. Humans have genius, have that creativity.

“I've always said it, they'll never kill off the spirit of rock and roll. The human experience will always live on.”

Mark does touch upon an area where he feels there may be a change caused by generative AI.

“I wonder how much TV production companies will cut costs, by thinking, we're not going to employ a specific composer, or buy licensed music, We're going to go onto an AI thing, put in variables and create music that way. I think that will happen, some composers are concerned about that.”

Dr Robert Laidlow, a composer and researcher at The University of Oxford, also feels this could be a case where technology may be used as a cost cutting measure - so that a human composer is not needed.

“What we haven't really seen before is just how much power some of these big technological corporations might have over consumerist music in the sense that there are certain musical genres where we're just going to say that's fine, we don't need a human to do that. I'm happy with AI generating it. Advert music is surely going to be like this.

“Where's the line for people accepting AI music? Film music? I don't think you're going to get something like Oppenheimer with an AI generated score, but you probably will get some lower budget ones.”

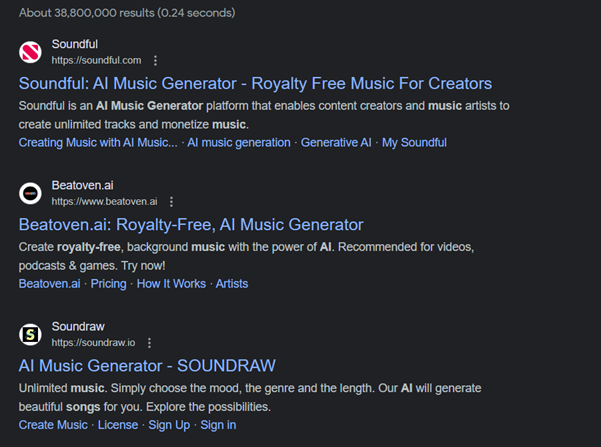

Even a quick Google search reveals there are already many companies offering AI generated music that seemingly fit into the ‘advert’ or ‘stock music’ mould.

But the success of some suggest they shouldn’t all be dismissed as merely tools to accompany low-budget video production.

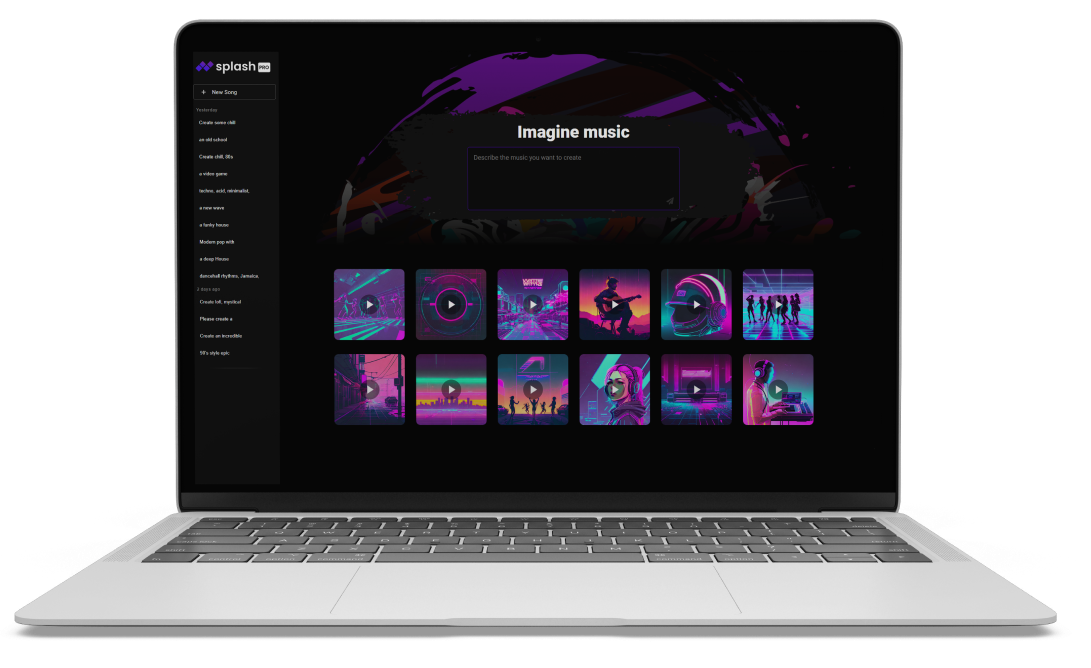

Australian company Splash Music is one of these, and is a platform which allows users to type a prompt to generate music, but also rapping or singing.

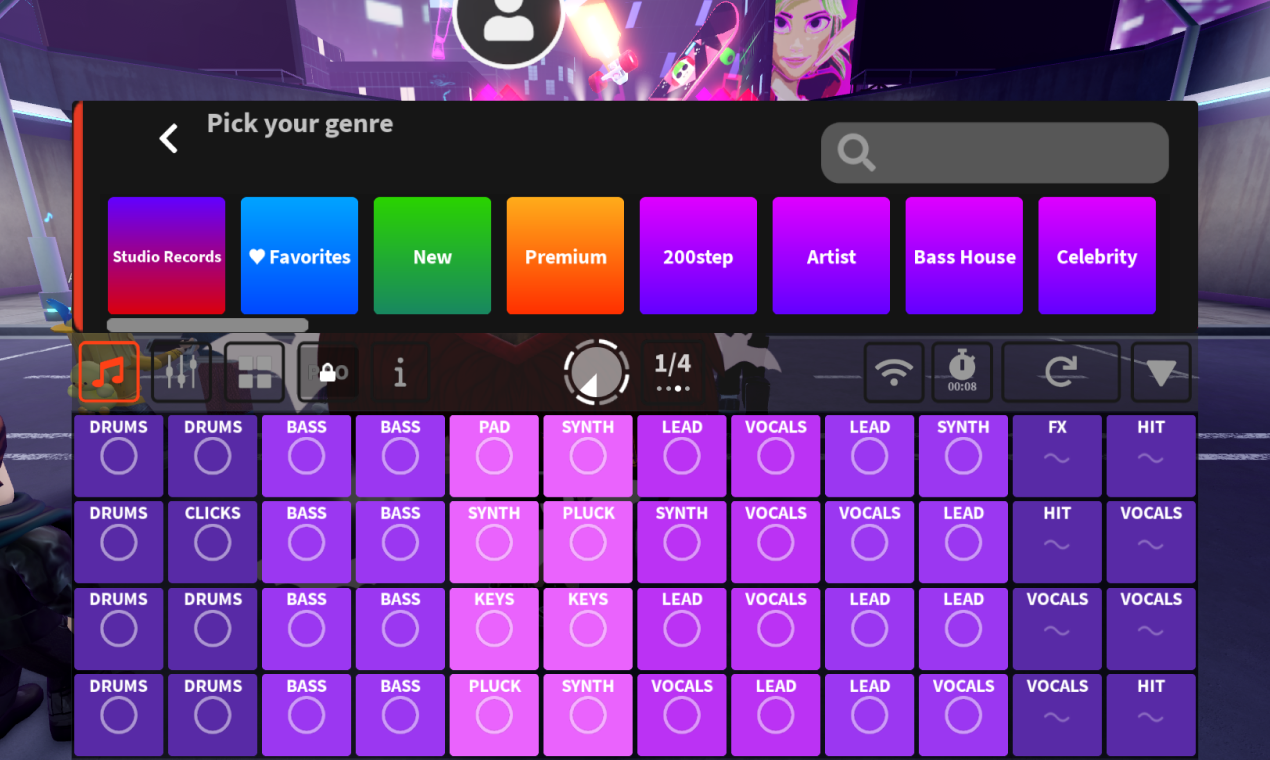

Splash, which was founded in 2017, launched an AI-powered music game within the extremely popular online platform Roblox', which was played over 128 million times within the first year of its launch in 2020, and still gets over 95,000 unique users making and performing music per month.

Michelle Dintner, Chief Strategy Officer, says while the music generation works differently in Splash Pro, she sees the popularity of the game is evidence that younger generations have a different relationship with music.

“There is a demand amongst young people to have a more interactive relationship with music. They are no longer just passive listeners, they want to make the music that they want to hear.”

The model that powers the software is trained by a dedicated music team, and Michelle says the music industry is simply following developments that have already happened in art and video production.

When asked about the concern around AI and it taking the ‘human element’ out of music, she stressed they saw AI music as an addition not a replacement, and stressed the potential for ‘new’ kinds of music instead of the erosion of familiar forms.

“We see AI as being purely additive and overall increasing the size of the music market that benefits everyone including the commercial music industry and traditional artists.

“We hope to see more people making music than ever before, and to see new genres emerge and a new type of artists emerge that may not have been empowered to make music before AI tools existed.

"We’d also like to see established artists using AI to change how they promote their music, grow and interact with their fans in new and exciting ways that were previously not possible.”

"There are certain musical genres where we're just going to say that's fine, we don't need a human to do that"

Dr Laidlow produced a large-scale orchestra piece for the BBC Philharmonic, where each movement utilises a different aspect of AI.

These are only a few examples of the many 'AI Music Generator' sites

These are only a few examples of the many 'AI Music Generator' sites

Splash's AI Music interface within their game in Roblox

Splash's AI Music interface within their game in Roblox

For their computer software, all a user needs to do is type a prompt and pick a style

For their computer software, all a user needs to do is type a prompt and pick a style

The idea of seeing exciting potential or being intrigued in the ‘new’ the use of AI in music could lead to, was also shared by several experts.

Dr Nick Bryan-Kinns for instance, is currently researching what happens to AI generations when we 'let them lose' and don't simply use them as baseline, and how this may change as the technology progresses even further.

Whilst it seems we are in the midst of a technological ‘revolution’, it’s probably worth keeping in mind (if only for peace of mind), that music has always been to some extent evolving in line with technology.

Cliff Fluet breaks into a passionate rant as he hammers home this point.

“The phonograph was invented by Edison. Not Mozart, not Beethoven - Edison.

“AI is a tool, right? It's like electricity. It's really, really useful.

“But if you get hit by it - it’s not fun.”