An Unexpected Partnership:

The funding scheme bringing farmers and climate groups together in the Peak District

Farmers in the Peak District have been working with climate groups to implement sustainable changes thanks to a programme that provides funding to nature-friendly farms.

The Farming in Protected Landscapes (FiPL) programme, which was introduced in 2021 and extended to 2026 in February, invests in projects that support and improve National Landscapes, National Parks and the Broads along themes of climate, nature, people and place.

As of 2025 almost £6m has gone into over 300 projects in the Peak District, with £59m spent across the country.

Andy Farmer, FiPL Engagement Officer at the Peak District National Park Authority, says the success of the programme is down to its flexibility compared to other schemes, such as the Countryside Stewardship (CS) scheme.

CS requires farmers and land managers to sign on for multi-year agreements and complete a specific set of requirements, while FiPL provides a lump sum to cover the cost of a unique project for an individual farm or land holding.

“It’s not about battling against, it’s working with people. We can work without their confines,” he says.

As farmers are reliant on subsidies there has been a high level of uncertainty after the seven-year post-Brexit transition plan was implemented which will gradually eliminate Direct Payments.

A significant change came in March 2025, when the Sustainable Farming Incentive abruptly closed applications without the required six-week notice period.

This makes FiPL and the remaining funding schemes even more important to farmers and climate activists alike.

Andy Farmer, Engagement Officer for FiPL at the Peak District National Park Authority, explains the criteria for receiving funding under the scheme.

Projects funded in the Peak District have included cattle collars that restrict grazing to specified areas, milk vending machines allowing the public easy access to farm-fresh products, and the purchase of a drone to help track changes in the natural environment.

John Mead, Warden at the Eastern Moors Partnership, worked on the drone project.

This is a thermal image of red deer taken from the drone purchased by the Eastern Moors Partnership through FiPL funding. Thermal imaging allows the animals to be detected from tens of hundreds of metres away and improves visibility in low-light. This helps wildlife surveyors to find and track species in any conditions.

While agriculture is a known contributor to climate change, FiPL has brought farmers and climate groups together on projects that both support the natural landscape and encourage economic development within the park.

Beginning in 2022 the Hope Valley Climate Action Group began a hedge planting project funded by FiPL that worked with local farmers to replace fences with hedges.

Hedgerows are as effective at storing carbon as an equivalent area of woodland, despite generally growing much lower.

Natural carbon sinks are important because excess carbon in the atmosphere increases the natural greenhouse effect, which is causing global temperatures to rise.

For farmers, hedgerows shelter livestock from weather and slow water coming off the moors, which reduces flood risks.

David Hughes, Land Group Coordinator at Hope Valley Climate Action, explains that initially many farmers were skeptical of the project, as the Peak District is a deprived area and farming there already comes with many challenges.

While he says some farmers were fully on board with the transition to environmentally-friendly practices, others just “follow the money”.

He says FiPL has given the group a way to incentivise farmers towards sustainable changes.

“We definitely have areas where we disagree with the farmers. They see that they should be producing food, and many don’t see the environmental issues, but they will make changes when the money is there,” he says.

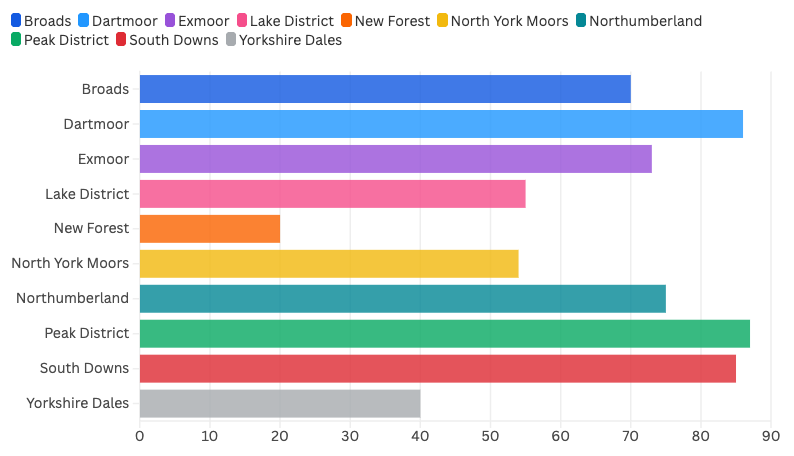

The vast majority of the land in the England’s ten national parks is farmed, making them a global anomaly.

In the Peak District National Park agriculture covers 87% of the landscape and the presence of farmed land alongside important ecological sites presents unique challenges.

Agriculture contributed 12% of UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2022, accounting for 70% of nitrous oxide and 49% of methane emissions, according to the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero.

Methane is around 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere, and nitrous oxide is 300 times more potent.

Livestock and agricultural soil are particularly notable emitters of methane and nitrous oxide respectively, and the farmed land in the Peak District is primarily permanent grass and rough grazing for livestock.

While some farmers have been against climate change mitigation, many have recognised that a warming planet and shifting weather patterns will impact their livelihoods.

The FiPL scheme has given farmers and climate activists a shared goal, which Mr Farmer, FiPL engagement officer, says makes it important to continue.

He says: “Because it has been so successful within the national park, and it’s locally run by people on the ground rather than remotely, and it's so flexible, and you can work with individuals to design an approach, it would be crazy not to keep it going.”

Percentage of farmed land in each of the National Parks in England. Data source: National Parks UK

Percentage of farmed land in each of the National Parks in England. Data source: National Parks UK