Bloodbath

PCOS, period politics, and a pandemic: the story of a collision

*The following article covers issues related to mental health, childbirth, thoughts of suicide, transphobia, and weight gain/loss*

Journalist Kirsty-Louise Card is shooting a vlog. She stares at the camera, her eyes alight with green eyeshadow, astonishment, and relief.

"It's taken so long for anybody to listen to me," she exclaims.

The reason for such vibrant joy?

Ms Card, 23, was about to start a medication that her doctor said she should have been prescribed years back, when she was first diagnosed with an incurable condition.

It is called PCOS.

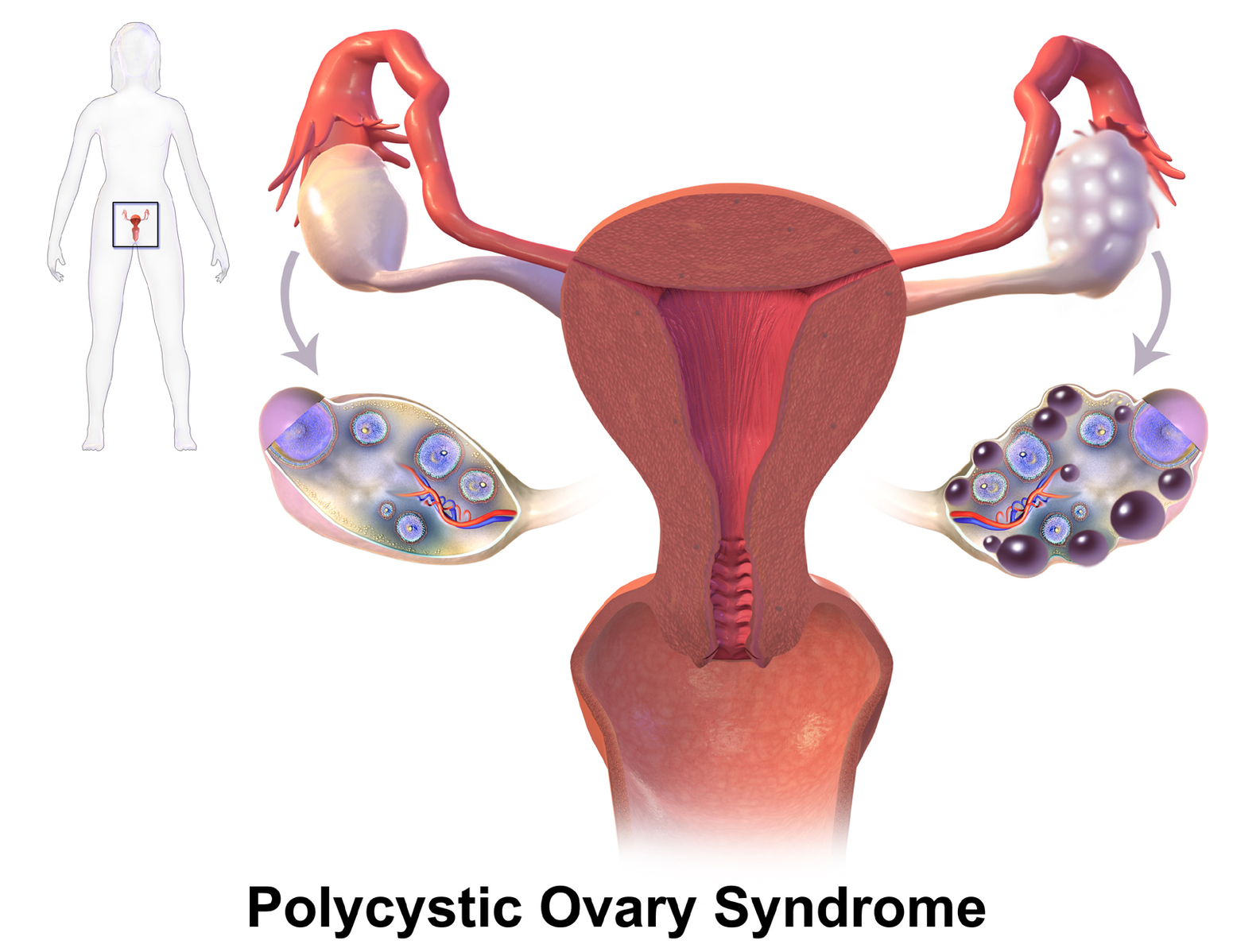

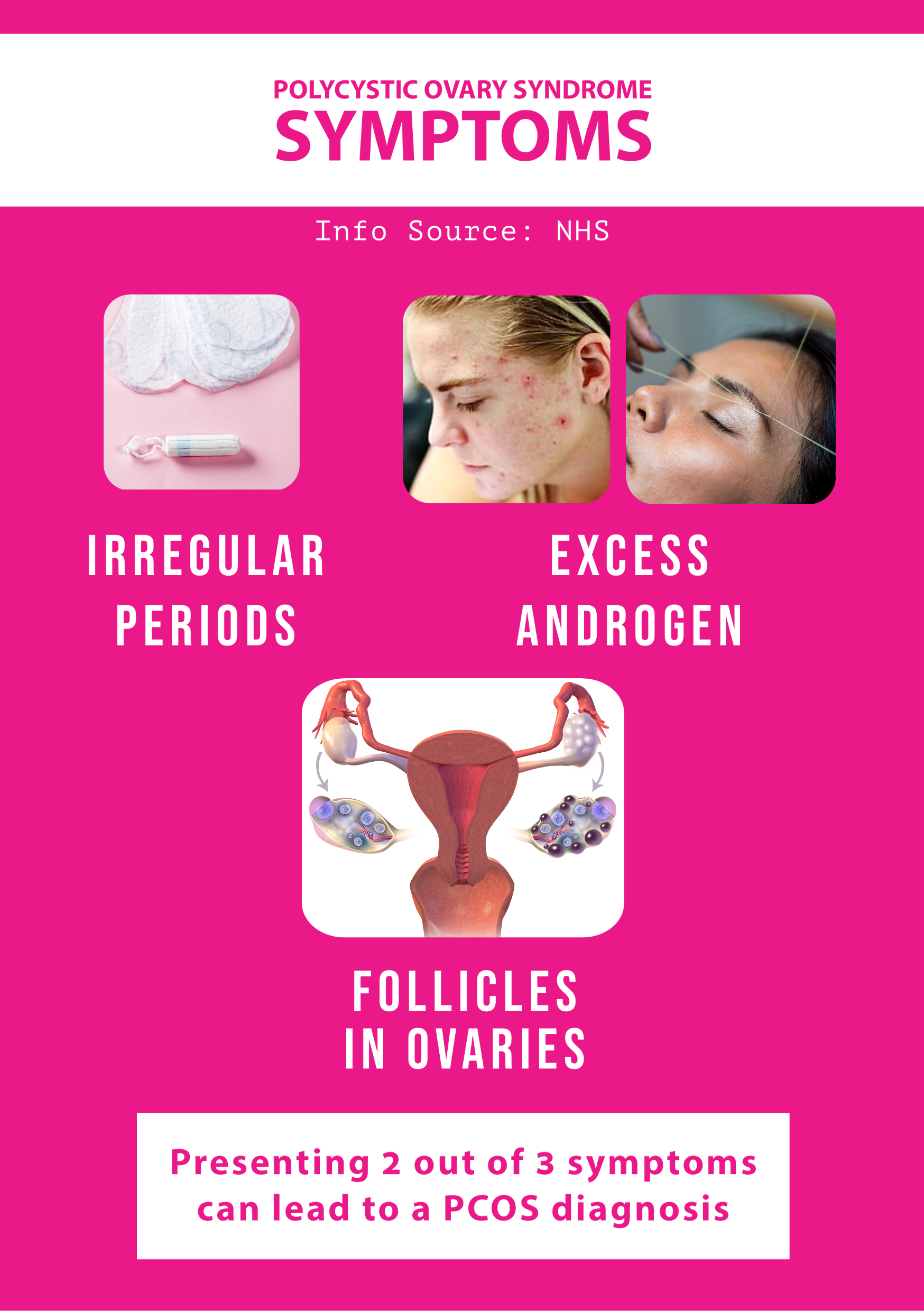

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome affects about one in every 10 UK women, while some estimates put the rate at around one in five. It sounds like a public health crisis: the perfect target for a nationwide health campaign.

But in reality, the condition is under-researched and often goes undiagnosed for years. Though studied by experts as early as 1935, a cure for this endocrine disorder is still unknown and its treatment is full of inconsistencies, often leaving those who have it to fend for themselves in a medical system with a record of ignoring women's pain.

PCOS patients can experience symptoms such as uncontrollable weight gain, facial hair growth, acne, and irregular periods. In later stages, it is associated with depression, diabetes, infertility, and endometrial cancer.

Birmingham resident Ms Card first began showing symptoms at age 14 but her doctor told her she would outgrow them.

She said: "I was having really bad mood swings to the point where I was quite angry or upset all the time. I was having bleeds constantly that didn't make sense, and really bad acne, hair growth, and everything else.

"I was going to the gym, I was trying to eat as best as what I could—and the weight just wasn't coming off. I didn't understand why and it was very upsetting, especially being a teenager. You've got doctors telling you that you're just not pushing yourself hard enough when I was physically exhausted all the time, and nobody was noticing."

After many arguments with doctors, Ms Card was allowed to see a specialist dietician.

At age 17, she finally received her diagnosis.

PCOS comes with painful physical symptoms and mental health challenges. Diagnosis can be delayed by years and treatment methods are still unclear.

How are people making sense of this incurable condition?

With global cases crossing 25 million, the coronavirus pandemic has forced healthcare systems into overdrive, while lockdowns brought normal life to a freezing halt.

What happened to patients with health issues that were being sidelined even before COVID-19?

Globally acclaimed author J.K. Rowling's comments this summer on menstruation triggered furious debate about women, their bodies, and those using the services meant for them.

Who is being erased in a world that is expanding beyond the male-female divide?

"We tend to put emphasis on what we think womanhood is, rather than what it actually is."

Stealing Sex: the impact of PCOS on mental and social well-being

The Thief of Womanhood sounds like a bad summer thriller but is really the title of a 2002 research paper that interviewed 30 women with PCOS to explore how they felt about their condition. Though ancient by medical standards and with a sample that lacked racial diversity, the paper is important for the way its researchers acted almost like journalists; they set aside data and complex medical terms to instead highlight the women's deeply personal comments.

During the study, nine out of 30 women used the word "freak" or versions of it to describe themselves or their PCOS experience. Bodily hair growth felt shameful to these women, while using medicines to induce their periods or needing fertility treatment to conceive a baby was devastating.

The Thief of Womanhood did not mean to say that PCOS took away the interviewees' identity as women, but rather that its effects (absent periods, increase in 'male' hormones, weight gain, fertility problems, excess hair growth, etc.) chipped away at society's image of the "normal" woman and her femininity.

What happened next is easy to guess: the study's volunteers described not only their physical symptoms of PCOS, but spoke in detail about its harsh toll on their mental health and social well-being.

Almost twenty years later, Ms Card would do the same.

"A burden on the state": PCOS during the pandemic

Ms Card's three year struggle for her diagnosis is a classic example of the medical trivialisation patients often face when trying to access support and care for issues related to reproductive health. Symptoms that crush patients may be considered minor by doctors. Contraception pills might be prescribed even before a diagnosis is made, and patients are often shamed into waiting until their condition becomes life-threatening.

In August this year, a mother was given £500,000 as compensation after her Endometriosis went undetected for 17 years. Doctors' dismissal of the Derbyshire woman's symptoms led to her needing surgeries, and becoming infertile.

For women and/or marginalised patients, being told their symptoms are natural, exaggerated, or even imaginary is a common experience when they express worries about their health.

Occupational Health nurse, reading out the health conditions in the form I had to complete like she’s trying to catch me out: “What’s PCOS stand for? ”

— Liesel Łempicka (@EmpickaLiesel) August 22, 2020

“What do you mean by fibromyalgia?” 🧐 Then, in a derisory tone: “So, we’re supposed to feel sorry for you, are we?”

Now, add one coronavirus pandemic.

What do restricted access to health centers, closed businesses, overwhelmed services, exercise restrictions, mass job losses, and months of stress mean for those suffering from health conditions still vying for better research and treatment methods?

Wanda Georgiades, PR manager of CARE Fertility, a clinic that also treats PCOS patients, said: "The pandemic [saw] a total shut down of our services. Patients had to stop medication, postpone treatments, consultations, and our clinics were closed. They are now open again and patients are coming through but the delay does cause anxiety, worry, and IVF is stressful enough."

But during the lockdown, some housebound patients wondered if their emergencies even mattered.

Neelam Heera is the founder of Cysters charity. In five years, the support group has worked to address poor public knowledge about reproductive health, and help sensitise the ethnic community to issues ranging from period poverty to mental health.

Ms Heera explained that menstrual pain has been normalised because culture taught women to adopt a "grin and bear it" attitude regarding their reproductive health. Even before the pandemic, women had a tendency to downplay their symptoms out of fear of wasting the doctor's time or "being a burden on the state."

Ms Heera said: "In the first few weeks of the lockdown, what we saw is a lot of confusion in terms of going to see GPs and doctors. Some of our women that were struggling and in pain felt that if they ring their GPs and doctors, they weren’t going to get referred.

"When you're at home having an endometriosis flare-up or you're bleeding uncontrollably, when you're ringing 111 - as everyone was doing around COVID - they were unable to get through, so they were sort of having to bear with the pain at home. We found that a number of women weren’t getting access to things like their contraceptive pills or any pain-relief that they were taking, because of the [first] lockdown. I think this is slowly getting better but it is still a problem at the moment for a lot of people. I think a lot of women are reluctant in this climate to come forward and say they’ve got these issues."

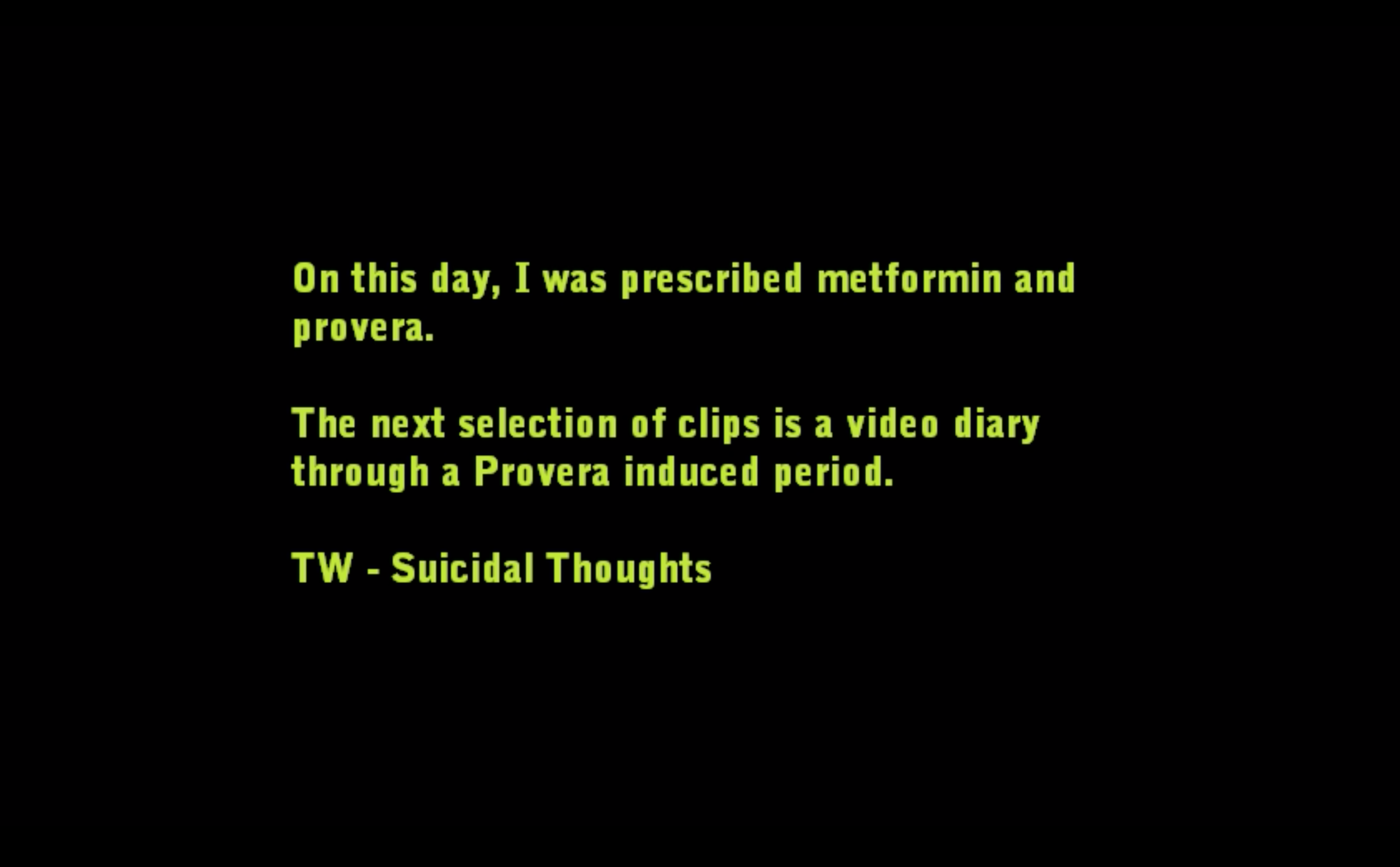

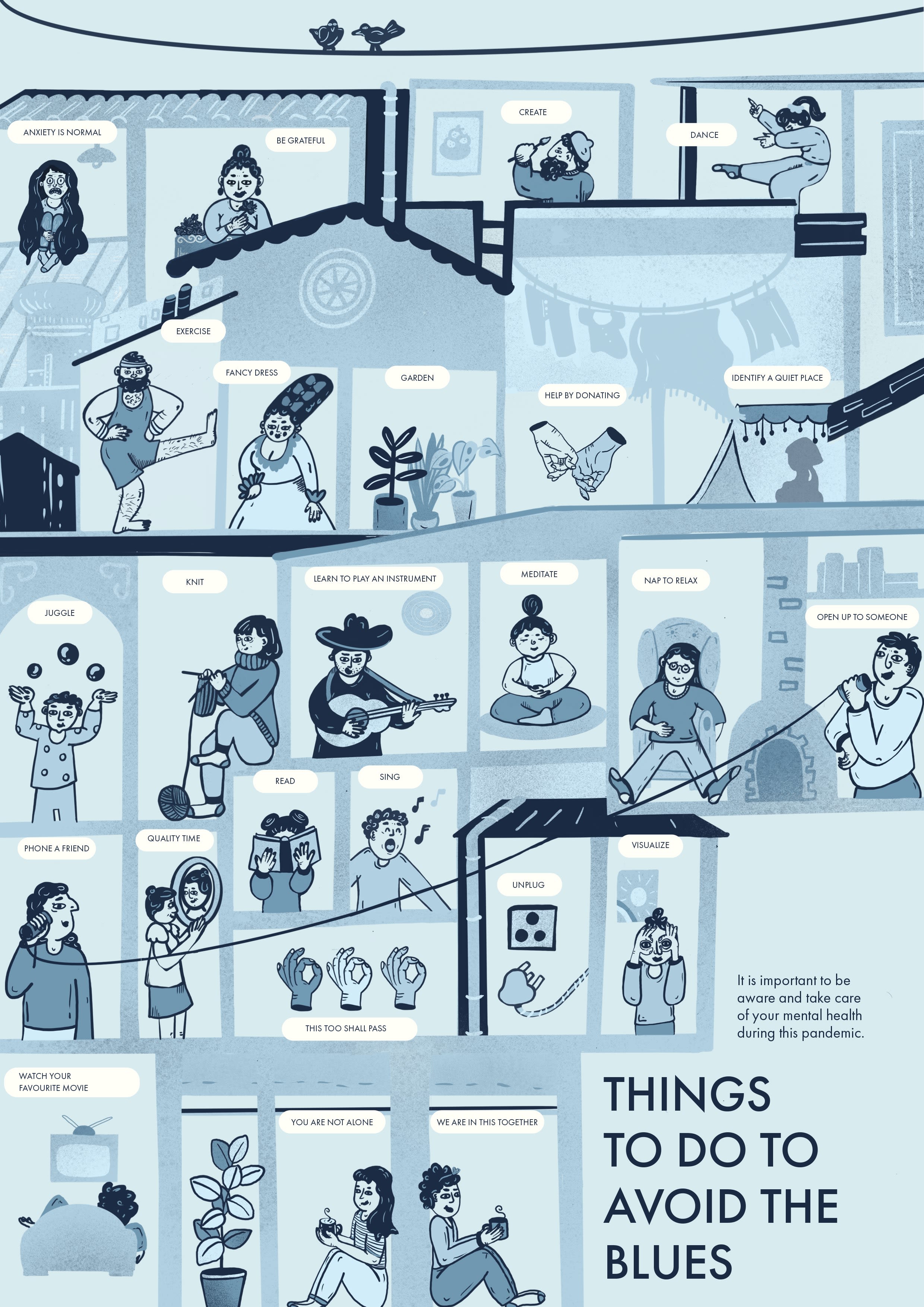

For some who had PCOS, like Ms Card, the lockdown brought about better eating habits and more time for self-care. However, due to the mental health effects of the condition, she experienced mood swings and "horrific" thoughts about dying alone.

A still from a medical video diary by Ms Card [image credit: Kirsty-Louise Card]

A still from a medical video diary by Ms Card [image credit: Kirsty-Louise Card]

Ms Card's strategies for enduring the first lockdown and regulating her mood included staying in touch with friends, doing homework, going for long walks, and eating well.

She said: "When you have quite a severe episode of poor mental health and if you then become very self-hating, you don't want to look after your body and that happened to me over the last year. I'm trying to regain some of the self-love I used to have but obviously easier said than done. I will be able to, eventually. These things just take time."

The Birmingham Live journalist recorded her weight loss journey without censoring the challenges she faced [image credit: Kirsty-Louise Card]

The Birmingham Live journalist recorded her weight loss journey without censoring the challenges she faced [image credit: Kirsty-Louise Card]

Ms Heera also confirmed that PCOS has strong links to mental illness. She added that living in chronic pain while looking normal meant having to balance society's expectations while surviving an "invisible" condition.

She said: "For healthcare professionals, I understand that they’re under a lot of stress, but I think it’s really important they recognise that the women aren’t coming forward unless they really need to."

Cysters founder Neelam Heera explains why communities need to have better conversations about PCOS [photos credit: Neelam Heera]

Cysters founder Neelam Heera explains why communities need to have better conversations about PCOS [photos credit: Neelam Heera]

"Being the family letdown": PCOS and self-worth

Cultures around the world place heavy importance on menstruation and fertility, often defining a woman by her biology and assuming that she will become a mother.

Ms Heera, who comes from a South Asian background, shared the story of another woman from the community who was diagnosed with PCOS around 15 years ago. When the doctor explained that she needed to lose weight and might have fertility issues, the woman's mother began crying. Family conversations about PCOS traumatised the daughter so badly that she decided not to find a partner or have children. She felt "unworthy of being a woman" or a wife to someone.

"We tend to put emphasis on what we think womanhood is, rather than what it actually is," added Ms Heera.

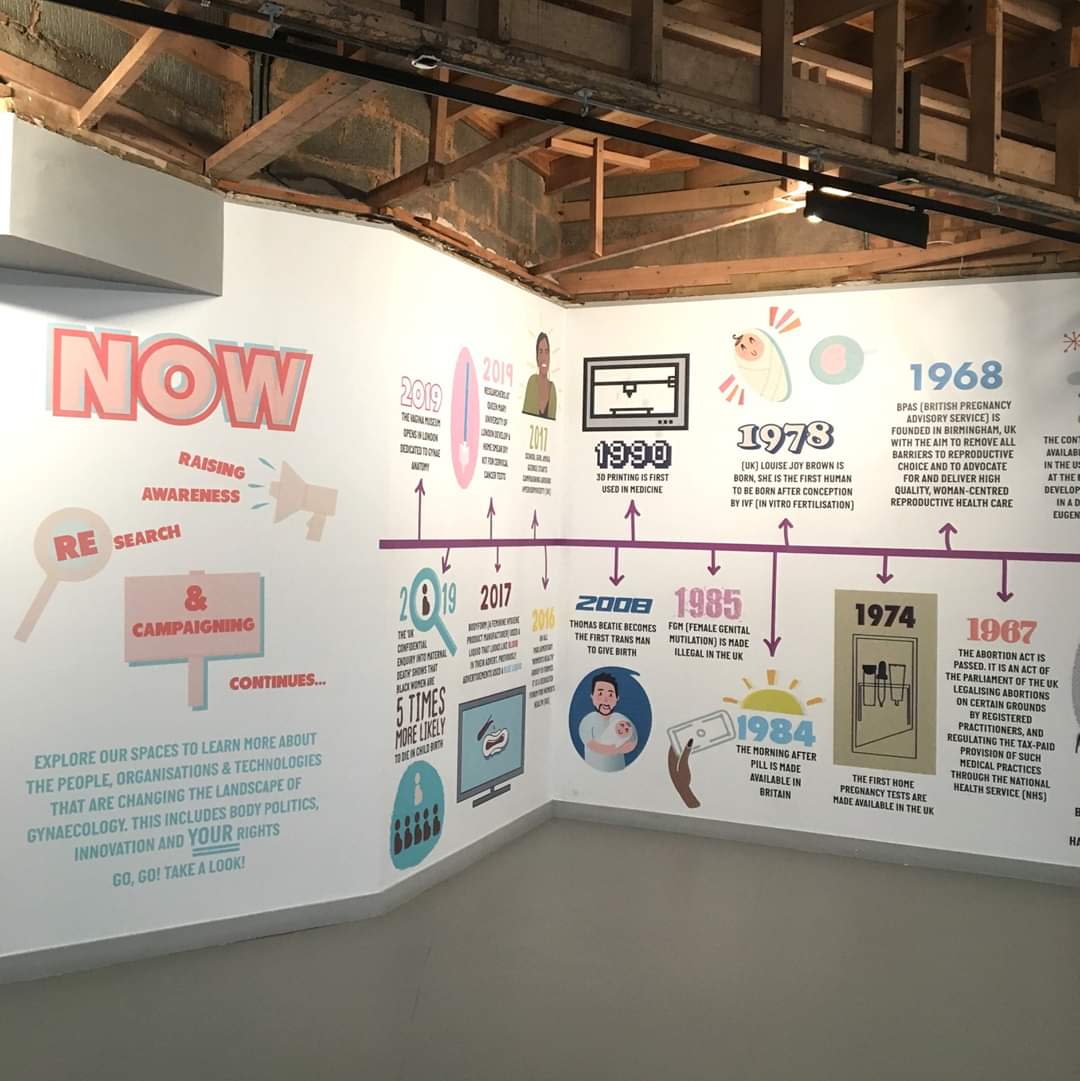

Writing on the Wall of Silence [image credit: Neelam Heera]

Writing on the Wall of Silence [image credit: Neelam Heera]

PCOS is actually an endocrine condition that can result in heart disease and diabetes, but its effects on fertility have caused it to be largely seen as a reproductive disease.

CARE Fertility's Ms Georgiades said there was also a need for better conversations surrounding fertility issues and in vitro fertilisation [IVF].

She said: "Fertility in the media has often been controversial. It was once cloaked in secrecy but that doesn’t help patients move forward. There is of course a need for confidentiality and privacy but we believe that access to information is crucial and we do try to use the press to influence understanding and empathy for what is a very common issue."

Fertility isn't the only barrier; medical fatphobia and the weight stigma attached to PCOS also stop those with the condition from seeking help.

In a period of about three months, Ms Card's weight went from eight and a half stone to 14 stone. Over the next few years her weight both rose and fell several times, but a dietician told her she would probably never reach a healthy weight without surgery. Ms Card was shocked by the comment.

She said: "They shouldn't really say that to anybody who's trying to battle their weight, because it kind of sets them up for failure already. But thankfully I'm a bit more stubborn than that. So I will go for it."

Ms Georgiades explained the NHS applied a weight criteria for patients, and set BMI limits that affected funding.

She said: "We know that weight can be linked to fertility and we take a positive view to help our patients be as healthy as possible before starting treatment. Weight can affect treatment – administration of drugs, anaesthesia, etc. It is also well known that being overweight can affect pregnancy. All of these issues would be picked up with any patient we felt needed help. Lots of our patients are aware they need to lose some weight, and lots do just that."

But activists like Ms Heera and people with PCOS have called for more holistic treatment methods that address the current health needs of the patient, rather than always making a patient's (assumed) pregnancy the centre of discussion.

as a woman who has PCOS, i always feel left out in the conversations because i'm not trying to conceive a family but it still affects me.

— ɐɾnɹq uʍoɹq ǝlʇʇıl (@sirenlecrush) July 21, 2020

On the other hand, Ms Card made it clear that she was mainly fighting her PCOS in order to prevent infertility. Hopeful of having children one day, she spoke about how society's expectations have become part of her own life plan.

What does it feel like to fight PCOS? [vlog excerpts and photo credit: Kirsty-Louise Card]

"Disrupting the Binary": Exploring gender diversity

Standing in a shop's check-out queue while holding a pack of sanitary napkins, Manpreet Singh defies a world that seems determined to see nothing beyond categories of male and female.

Other customers stare at the 26-year-old author and artist; they are unused to the sight of a man openly buying menstrual products.

No one has asked but if they did, Mr Singh would be happy to clarify that the pads are for himself.

By living and sharing his experiences, the 26-year-old hopes to disrupt the gender binary. [image credit: Manpreet Singh]

By living and sharing his experiences, the 26-year-old hopes to disrupt the gender binary. [image credit: Manpreet Singh]

During a phone interview, he said: "I am a transgender man. Depending on the day, I define as either transmasculine or non-binary. It really just depends on me and my gender dysphoria."

Mr Singh began transitioning when he was 20, with a combination of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and surgery. His mandatory pronouns are currently he/him.

Mr Singh has spoken out strongly against the gender binary - the narrow categorisation of male and female that he felt was promoted even in the LGBT community.

Manpreet Singh explains how the gender binary also affects transgender people

By sharing his own experience, Mr Singh said he "makes people question what they have been taught."

He explained: "Every time I out myself, I am risking myself and my life because a lot of people murder trans people at horrendous rates. Even where I'm from, there are a lot of horrible stories about trans women and trans men getting raped and killed. So I disrupt the binary by just talking about my experiences."

A transgender Sikh man born and raised in California, USA, Mr Singh's views on gender were also shaped by his faith and his identity as a Panjabi.

He added that transgender people faced discrimination and ignorance even in professional settings. Once, while doing a pregnancy test, a doctor asked Mr Singh if he had ovaries.

He wondered: "Why is this man here if he doesn't know that there are people with different bodies than him?"

This is not rare; transgender people who go in for medical treatment must often educate their own doctors. At worst, their lives are put in danger by the ignorance or prejudice of healthcare workers around them.

As someone who menstruates, another challenge for Mr Singh has been the absence of facilities in male public toilets, and the discomfort he felt because of the lack of privacy.

He said: "I would love for there to be actual stalls in men's bathrooms all the time. I hate that there's a urinal and a stall, because sometimes the stall is messed up, sometimes it's clogged so I can't even use that bathroom, and I don't like the idea of a urinal because I can't use that. I feel like accessibility is such a huge issue for us."

He added that gender-neutral bathrooms were a "safe space" as he could be certain of finding pads and a trash can there, if needed.

Mr Singh said: "Pads and menstruating is always focused on women, but there are even women who don't bleed, women who don't have a uterus - like trans women - and there's women who've had cancer. I just feel like making it gender-neutral would be making it inclusive to all. So they need to stop saying feminine hygiene products. Let's just say uterus products. It's easy.

"Simple things like that could change the world and make it safer for people like me."

Manpreet Singh shares how he feels about his periods

Everything is binary-

Limited to two options,

Is there really a

Freedom of choice

If we can only choose

Vanilla or Chocolate?

The lines are from Mr Singh's book Singh is Queer, which explored intersections of experience, trauma, and identity.

The Panjabi author and artist's work revolves around intersectionality [image credit: Manpreet Singh]

The Panjabi author and artist's work revolves around intersectionality [image credit: Manpreet Singh]

He said: "I love poetry. I love spoken word. I feel like that is an important way for me to express myself."

Growing up, Mr Singh loved Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling and had read her books by the time he was 12.

However, a few of her tweets this summer forever changed his idea of her.

‘People who menstruate.’ I’m sure there used to be a word for those people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) June 6, 2020

Opinion: Creating a more equal post-COVID-19 world for people who menstruate https://t.co/cVpZxG7gaA

J.K. Rowling's displeasure at the phrase "people who menstruate" rather than "women" expressed a belief that is common in several feminist subgroups: the idea that gender neutral language is erasing women, whose experiences have only recently started coming to the fore.

The author's later tweets and an essay on her website outlined her views on gender in greater detail. Over the following weeks, she was praised for defending women and she was harshly criticised for betraying them. Among her supporters were prominent radical feminist Julie Bindel and Guardian columnist Suzanne Moore. Those who opposed her comments included the period app CLUE and actor Daniel Radcliffe.

Hi @jk_rowling, using non-gendered language is about moving beyond the idea that woman = uterus.

— Clue (@clue) June 7, 2020

Feminists were once mocked for wanting to change sexist language, but it’s now common to say firefighter instead of fireman.

Mr Radcliffe, who played Harry Potter in the film adaptations of Ms Rowling's books, published a statement in support of transgender people and addressed heartbroken fans who could no longer love the series as they once did.

The Body Shop went so far as to offer the author educational reading material. Some supported the company's pro-trans stance but others said the message was hateful, considering Ms Rowling's history as a survivor of domestic abuse.

Hey @jk_rowling here's something we made earlier, we thought you might like one! We've also popped in a vegan bath bomb and a copy of Trans Rights by @paisleycurrah for you to read in the bath! pic.twitter.com/RNbPsSTS88

— The Body Shop (@TheBodyShop) June 10, 2020

Mr Singh said: "To hear her have so much hatred towards my people makes me not love her so much. I feel like anybody who is a bigot doesn't really matter to me because bigots are the reason why my life is in danger every single day. So what J.K. Rowling said is not only dangerous: it is harmful, it is genocide. She's trying to erase people."

Both J.K. Rowling and Manpreet Singh agreed that someone is being erased.

The question is, who?

Most people might struggle to see how one Twitter user saying "women" instead of "people who menstruate" could be compared to genocide.

To understand how this came about, one must go back to the very start of the saga.

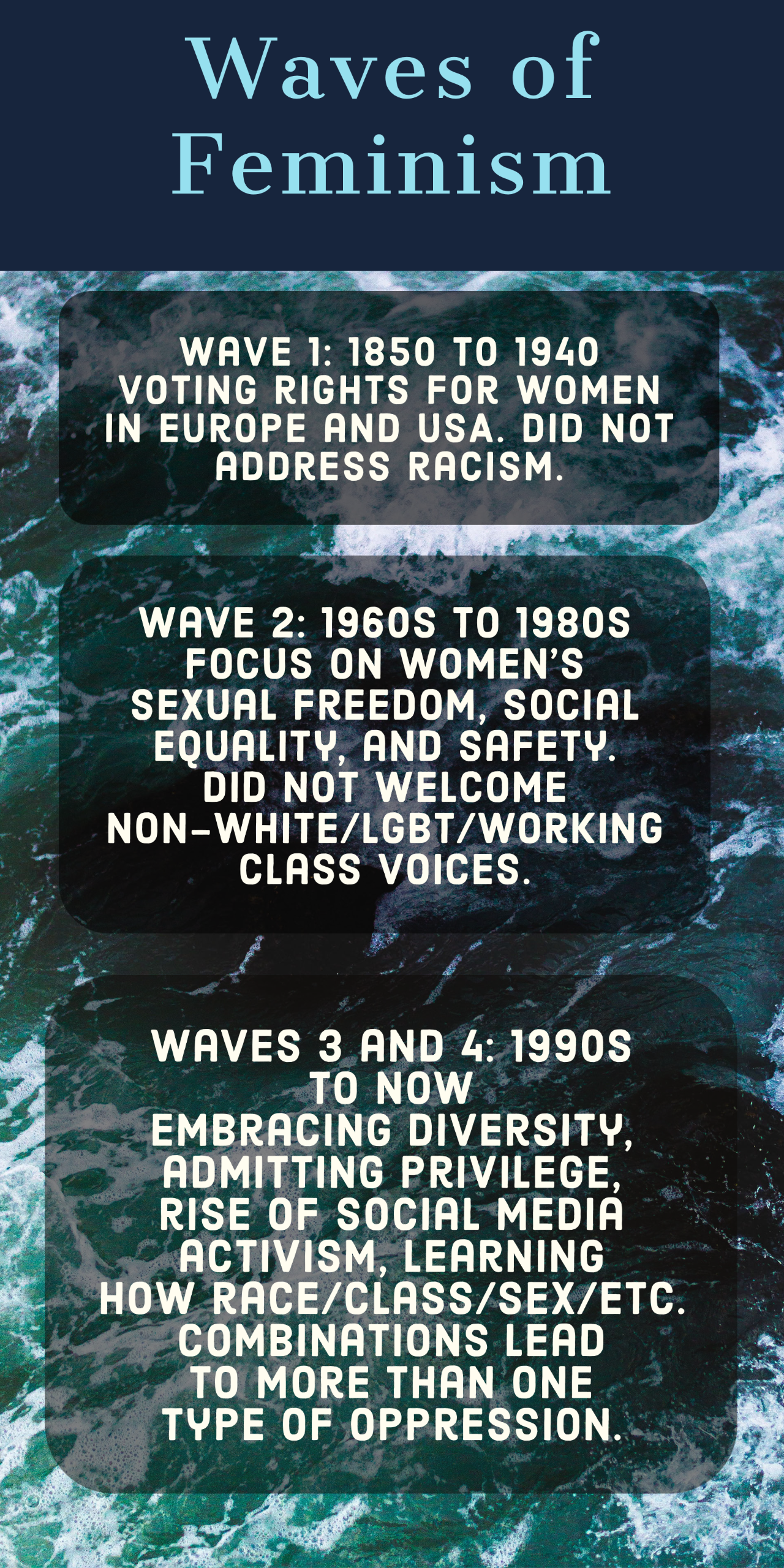

Feminism: a history of disagreement

"We have a hell of a lot more struggles than just our monthly bleed, I think."

Feminism, at its simplest, is defined as the equality of the sexes.

This is the definition most used in recent times, leading to a common view of feminism as an individual philosophy chosen and practiced on a deeply personal level. Actors, singers, and authors are commonly asked whether they identify as feminists, without delving into the nuances of the label or noting how these beliefs translate into real world actions.

One person's feminism may mean cherishing female friendships, while another might believe political activism is a must. Some feminists support pornography; others want it gone. Same with religious head coverings, make-up, bras, hair removal, capitalism, and even female-only changing rooms. The nuances of one's feminism are often lost under the colossal umbrella of a label.

It has been easy to forget that feminism is really a worldwide sociopolitical movement that fought for many different causes throughout the course of its 100+ year history. Differing ideologies are in ample supply and there exist dozens of unique branches such as postcolonial feminism, radical feminism, lesbian feminism, Marxist feminism, etc.

But like all global movements, feminism too came with its share of historical baggage and breakups.

Since the second wave, an ongoing challenge in UK feminism has been accepting transgender people within the movement. These discussions affect millions of lives, with the power to influence government decisions about NHS therapies, public toilet facilities, administrative procedures, and even prison regulation.

Campaigners in the country have called for transgender women to be kept out of spaces designated for cisgender women and children, claiming this is to prevent potential assault, or their re-victimisation after experiencing abuse (mainly from cisgender men).

However, transgender people are considered to be one of the world's most marginalised groups, facing disproportionately high rates of violence, hateful rhetoric, and discrimination due to unwarranted fear. Their presence is often questioned even within what members call the queer community.

From binary to spectrum: growing pains of sex and gender

"Maybe it's just the people around us who make it so hard, and make us hate our bodies, and make us believe that if we do change our bodies, maybe we will be accepted."

As a business, we strive to be inclusive and therefore, we allow customers the choice of which fitting room they feel comfortable to use, in respect of how they identify themselves. This is an approach other retailers and leisure facilities have also adopted. 2/3

— M&S (@marksandspencer) October 31, 2019

In late 2019, radical feminist campaigner Jean Hatchet demanded answers after a friend shopping with her daughter allegedly saw a man in the female changing rooms at Marks and Spencer. The retail outlet stated that shoppers could decide which changing rooms to use, in line with their identity.

The feminists who view transgender women as biological men or male-bodied people may call themselves radical feminists or gender critical feminists, as they believe only biological sex or birth-assigned sex is real. They are sometimes called trans-exclusionary radical feminists [TERFs] by others who feel their feminism cuts out transgender people. Many radical feminists feel the word is an inaccurate slur, as they claim their feminism includes anyone who was born female (even if said people do not wish to be identified as such). Women holding gender critical views found a powerful ally in J.K. Rowling, who shared what single-sex spaces meant to her as a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual assault.

In her essay, Ms Rowling wrote: "A man who intends to have no surgery and take no hormones may now secure himself a Gender Recognition Certificate and be a woman in the sight of the law. Many people aren’t aware of this."

While accurate, the claim belied the complexity of the process: UK government guidelines stated that those applying for a Gender Recognition Certificate need to have lived for 2 years in the acquired gender, and also submit documents proving so.

Trans activists felt that Ms Rowling's alarmist claim echoed the way gay men were (and in many societies, still are) portrayed as pedophiles, leading to homophobia and hate crimes. The statement presented an image of all transgender women as predatory 'men in dresses' - a stereotype erasing their realities and in many cases, long histories of pain.

With the sensationalism removed, the restroom debate largely boils down to this: radical feminists tend to view unisex/gender-neutral facilities as an erasure of women's safe spaces, exposing dominated members of the sex binary (females) to those who carry out the domination (males). Meanwhile, others see gender-neutral spaces as a way of recognising that gender and sex identities have always existed on a fluid spectrum. Intersectional feminists mostly choose to support self-identification rather than defining gender on the basis of one's genitalia.

More recently, the struggle has also come to include the evolution of the English language itself.

A recent article published by CNN was widely mocked online for using the phrase "individuals with a cervix." Labour MP Rose Duffield was criticised for liking a post that expressed gender critical views, and for later claiming that only women had cervixes.

Where periods are concerned, inclusive language is meant to address not just women, but also men who may have uteruses, and those who have menstrual cycles but are transgender, non-binary, and/or intersex. Inclusive language also addresses readers without implying that menstruation is a fundamental requirement of womanhood.

While many radical feminists saw the rise in inclusive language as an erasure of womanhood, others are neutral to the change or may even prefer being part of a growing movement that values correcting historical wrongs (equity) over uniform treatment for all (equality).

Ms Card was open to both gendered and inclusive language, but disagreed with Ms Rowling.

She said: "I am a menstruator, obviously, when I am lucky enough to bleed anyway. I am a cisgender woman, so calling me a woman's fine, too. I don't really get offended by inclusionary language. It’s literally referring to one part of womanhood which, as you know, isn't a thing for every woman.

"I believe that any comments about whether a trans woman is a woman based on whether they have a bleed, or whether they can carry children or not is completely ridiculous. It invalidates women who have fertility problems, and cisgendered women like me," she added.

Mr Singh believed that gender critical feminists were trying to create the concept of an outsider.

He said: "J.K. Rowling enforces that by saying people who menstruate are only women. So does she include trans women in that? I want to ask her what she really means, because trans women are women. So if I had the opportunity to speak to her I would say that you need to do some more reading because trans people have been here for over 4,000 years."

Several women's health organisations recently reviewed their policies or changed their vocabulary in order to better reflect gender diversity.

Last year, Cysters rebranded itself by changing its old name, adding a unisex slogan, and switching to gender-neutral language to support those with reproductive issues who may not identify as women. Ms Heera explained that Cysters was actually named after her own ovarian cyst, and that she didn't agree with Ms Rowling's comments "in the slightest."

She said: "We had people within Cysters who identified as non-binary and felt that because of the [previous] name, it wasn't a safe space for them. The reason I created Cysters was because, as a South Asian woman, I felt there was no place for me. I know how that felt, so I'm not going to be part of making someone else feel that way."

The decision was not an easy one. Backlash quickly followed and Ms Heera faced hate from internet trolls. One commentor said that she had "Thanos-ed half of the UK's population" with the name change, referencing a comic book villain who erased life with a snap of his fingers. Strangers sent emails, saying that they hoped the charity would shut down.

Ms Heera said: "At the time it was horrible, I really struggled. It made me question if what I was doing was the right thing, in all honesty. It was coming in thick and fast. But it was completely the right decision. Out of all of them we did have a few messages from people who identified as non-binary or trans and they felt included. So for all those hundreds of people saying that they weren't [included], who didn't need Cysters in the first place, to have one person speak out and say it was good for them was worth it."

Cysters was not the only group to make this move. In an emailed statement, Freedom4Girls (F4G) described itself as an "inclusive charity working to support women, girls and all people who menstruate."

F4G declined to comment on Ms Rowling's tweet but added that its "transperson inclusion policy" was in the process of being drafted.

Verity UK, a PCOS charity, did not respond to requests for comment but used gendered language throughout its website and referred to PCOS as a "female hormone condition."

Meanwhile, Ms Georgiades said: "We do believe that family is for everyone at CARE. We treat singles, LGBTQ, same-sex male and female couples, and will try our very best to use language that is appropriate."

Predicting a post-pandemic world

What will reproductive healthcare look like in the post-COVID world? The rise of telemedicine, the growing gulf between patients and experts, people suffering in silence and shame behind the digital divide - are these inevitable changes? Perhaps not, thanks to the people sharing their resources to create a more interconnected future.

Cysters has used social media to educate its community, helping members get more out of their limited time with overworked doctors or specialists.

Ms Heera said: "We’ve just started doing Instagram Lives and we’re going to be doing it with medical professionals to answer some of these questions for which these women would be ringing 111, or trying to speak to a healthcare professional generally. So if we can get these questions answered for them in a space outside of a medical professional’s, that might help the NHS in the current climate that we’re in.

"I think it’s both on the patient and healthcare professionals to support the patient."

Ms Heera (far left) leading a Cysters event before the pandemic [image credit: Neelam Heera]

Ms Heera (far left) leading a Cysters event before the pandemic [image credit: Neelam Heera]

Across the world in California, Mr Singh quit a transphobic workplace just before the pandemic and has been using the time to work on his writing and music. Technology helped him promote his first book, sensitise his audience to the experiences of gender non-conforming people, and take part in trans-Atlantic collaborations: earlier this year, he published an article with Cysters about his experience as a man who menstruates.

In the UK, CARE Fertility's clinics opened after the first lockdown eased, with a changed protocol to address the ongoing infection risk.

Ms Georgiades said: "If you are worried about your fertility, get help sooner rather than later. See your GP if you are trying for a baby and it's taking too long – ask for advice. There should be equal space given to discuss fertility and how life can impact [it]."

Meanwhile, Ms Card has used journalism, vlogging, and writing for the Cysters community in order to share the reality of living with a chronic health condition. She revealed her weight-loss journey and documented the side effects of her medicines for a "complete, uncensored version" of her PCOS experience.

She said: "When I was doing it before, a lot of women would get in touch with me and ask me for advice. Other women with PCOS would cheer me on and it made me feel better having a community there that I was helping at the time.

"I've got to really learn to love my body again, even though sometimes it feels like it's broken. But I know I can do it. I've had success over this before and I can do it again."

Image credit:

Author: BruceBlaus | Cropped from original image

Author: BruceBlaus | Cropped from original image