Can creativity help us out of a dark place?

Creative arts have been around for centuries but now organisations are starting to use them as a way to battle mental health disorders and trauma. Why?

Sheffield Flourish’s building is not immediately noticeable. The sizable brick building is hidden away from the noise of the main street, located in an alleyway with no shops or restaurants to draw people’s attention. The prominent sign decorating the building is not the one you’d expect to find; it is still holding the title of its previous purpose of use: ‘Sadacca: day care centre for the elderly’. Its current identity is acknowledged only by the inconspicuous poster glued on the door underneath.

Sheffield Flourish

It is a testament to the popularity of its purpose; an organization’s building is as distinguishable as its occupier’s reputation and creative arts have yet to be calcified as a popular method of healing. What distinguishes it today though is the lively music pouring from inside.

Entering on a Friday afternoon you will find a group of people very much resembling a band in practise. A mixture of ages and backgrounds, every single person is standing behind an instrument, forming a circle that generates only music and laughter. Watching them go through Rolling on the River as if they have been doing it for years the last thing that would come to mind is that the reason behind the music is mental illness. And yet, it’s true. This is a room of people still battling with their demons and, in a way, music is a big part of why they’re still here.

At the moment, according to World Health Organization, one in four people suffer from a mental disorder. Creative arts, having been widely associated with inner expression, can be a handy tool when trying to coax someone out of a dark and isolated time. The work being done in amateur art workshops has sometimes proven to give better results than a GP appointment; instead of asking the struggling person to confide in an unfamiliar face, they are given a more indirect and creative way to communicate- by, well, creating.

Art psychotherapist Matthew Clark described painting as a way that allows, ‘by means of the tone and medium’, feelings to be captured and scrutinised.

“The effect is” he said, “that the originally chaotic or frightening impression [of the situation] is replaced by a picture which serves as a conduit for the psychological exploration of the experience.”

By materialising their thoughts, the person is able to take a step back and really look at the situation from a different perspective. Similarly, with music they get the chance to step out of the chaos in their mind and focus on something else.

Benu Adam, the manager of the charity Arts, Mental Health and Wellbeing said that in the case of her organization, the focus is at “the process and not the result”.

“We try to bring people together in a creative environment because I do believe creativity gets people out of themselves in a very natural way”

In her workshops, art is used as a medium through which the participants learn how to let go of the idea of control. By doing abstract art or marbling, for example, where control is limited, they effectively learn how to handle not having control over the outcome of a situation- a concept that people with mental health disorders struggle with.

“You’re enjoying the process and, by the end of it, you’ve created this beautiful piece and it’s almost incidental because that’s not the aim.” says Ms Adam, “Doing something without the fear of being judged, without the fear of doing it wrong- we’re finding that’s the key with a lot of learners coming in with low confidence.”.

(Shot by Tom Tallieu Stephan)

"Creativity gets people out of themselves in a very natural way"

Paul Henderson, a member of the Open Door Music group, suffered a manic episode in his 40s that led to a bipolar disorder diagnosis, a suicide attempt and a three-year stint at Worthwood Hospital.

His tale could easily have ended there, lying in a hospital bed, but music sessions organized at the hospital re-generated his passion for the craft and eventually brought him to Sheffield Flourish. He now credits the organization for bringing him out of isolation and helping him regain his self-confidence.

“It’s funny” he said to me after a jam session of Time of My Life, “because people will turn up here and collaborate in a way that they wouldn’t even ask their neighbour ‘oh can you give me a hand to trim this hedge?’.

The evidence is also ample.

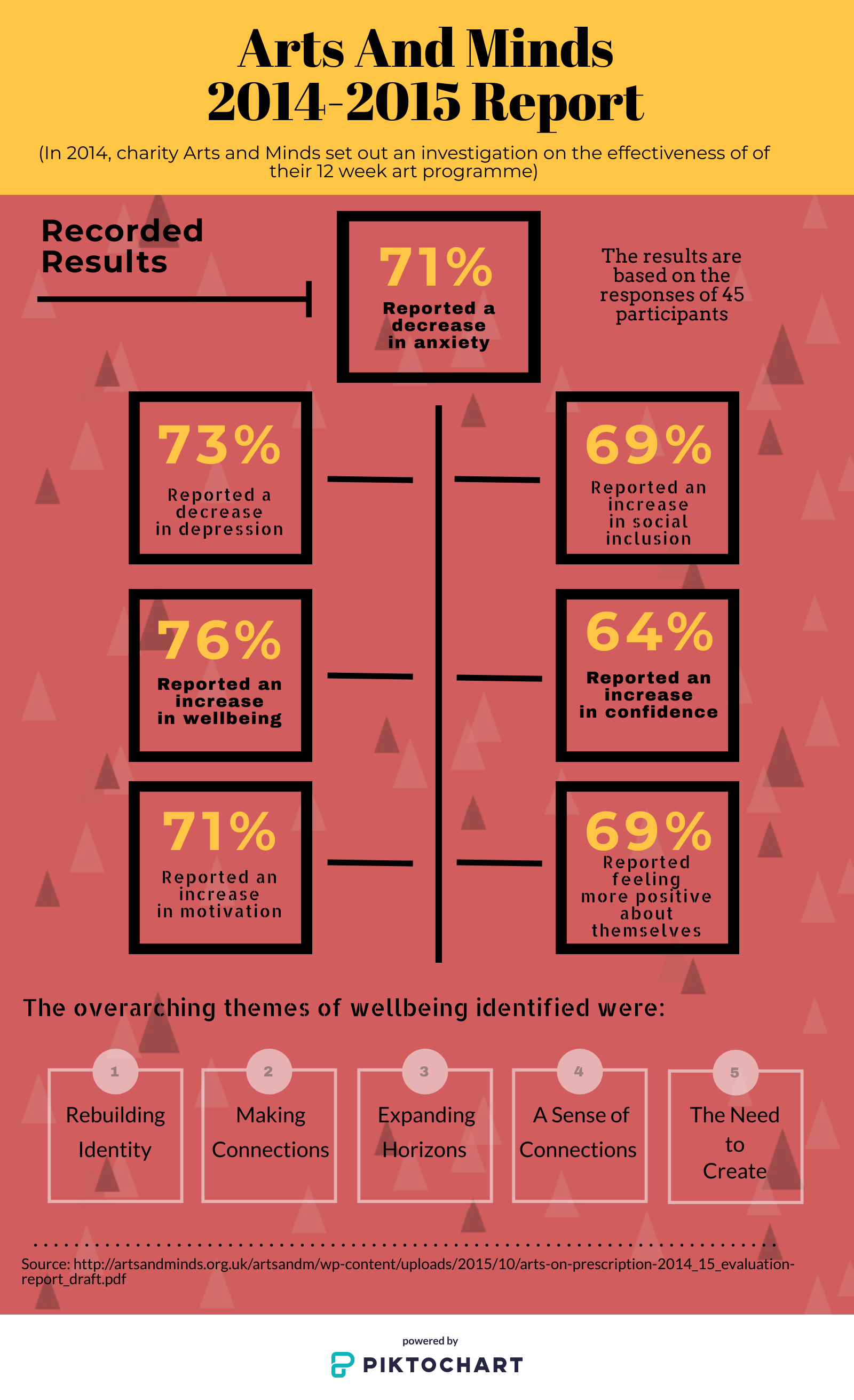

According to a research conducted by the charity Arts and Minds, art on prescription, whether self-prescribed or by a doctor, showed a 37% decrease in GP consultation and a 27% drop in hospital admissions. Similarly, an evaluation of their own art programme found that over 70% of participants reported an increase in well-being and a decrease in depression and anxiety levels by the end of it.

This shows that healing does not always come in the form of pills; something as mundane as picking up a paintbrush or strumming a few notes with others can summon back feelings of happiness and self-confidence.

The organization also uncovered that art, as a recovery method, equated to a saving of £216 per patient. On its own, the number does not amount to much, but during a time where the effects of the NHS crisis are felt across the UK, this number is a sweet melody to some ears.

Ultimately, though, creative arts are linked to one of humanity’s handiest tools; imagination. Armed with this, our ancestors brought us crucial scientific creations, cultural evolution, communication, and, of course, art. Like a muscle, it requires exercise to remain durable, but can be a great ally for anyone living with a mental illness.

Mr. Henderson spoke of creativity as a saving grace, little appreciated for the gifts it offers. “If we exercise our imagination by writing poetry, music, or doing any art, then when that problem hits us instead of going ‘oh my god it is a catastrophe’, which is how people with poor mental health often think, we’re like ‘oh dear, there’s a problem. I wonder how that could be different’.”

For centuries, art was viewed as a means of entertainment or an example of status; if you played an instrument you were an intellectual, if your living room walls were decorated with paintings you were an aristocrat with taste. However, the many people touched by art can attest to the fact that sometimes help does not confide between the walls of a squeaky clean hospital ward, but between colours and materials and sounds.