Catfishing and romance

fraud: the psychology

behind devastating,

dating scams explained

"First of all they burgle your wallet, and then they burgle your heart."

Someone you have met online asks you for a loan of £10,000. Do you give it to them? Of course not. You don’t know them. But what if they promise to pay you back? What if they manipulate you into thinking they are someone you can trust? Someone you could love? What then?

In the UK, over £21 million was lost to scammers using fake dating profiles in 2020, with an average of £7000 lost per victim.

According to the Bureau’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), 18,000 victims reported losses of over $362m in 2018 in the USA.

But the question remains the same: how do fraudsters continue to get away with it?

Although catfishing is not a new crime, people continue to be targeted via online dating apps and social media accounts, but a lack of societal understanding about how damaging these crimes can be means victims are reluctant to report their experiences.

The simplest way to define a ‘catfish’ is a person who deceives and manipulates someone else for their own personal gain. This can be done through romantic, platonic and even professional relationships.

From an outside perspective, it can be difficult to comprehend how people fall victim to catfishing and romance fraud, but delving deeper into the psychology behind these crimes can give an insight into why certain people are more susceptible to being catfished than others.

“As long as something seems right, you’re not going to question it.”

Dr Elisabeth Carter, Associate Professor of Criminology

When describing the psychological damage victims are exposed to, Dr Elisabeth Carter, Associate Professor of Criminology and Forensic Linguist at Kingston University, says: “Quite often the focus is on the financial loss or any other kind of loss, but the psychological damage is huge because what fraudsters are doing in order to try and catfish or to defraud people of money is preying on the trust and judgement of their victims.”

She argues that shame is wrongly associated with this type of crime because a victim’s trust is manipulated which then leads them to make poor choices of judgement: “Especially with romance fraud, it's psychological grooming as well.

“So you're making what you think are good decisions, but because your reality has been twisted so much, you don't realise that what you're being asked to do is not right, and it's obvious to everyone else but it's not obvious to you.”

According to the FBI 2019 Internet Crime Report, confidence or romance scams were the second most reported crime, with nearly 20,000 victims coming forward to say they had been scammed.

However, it is still suspected that many cases were left unreported, meaning it is a growing problem that is yet to be solved.

Becky Holmes, 43, is writing a book about the psychology behind catfishing and romance fraud. She explains how people are reluctant to report this type of crime because they are embarrassed and aren’t taken seriously.

She says: “That’s one of the things that really, really needs to change because the more that people are made to feel stupid, the less they're going to report it and the more that people will continue to get away with it."

Becky Holmes, 43 Photo credit: Becky Holmes

Becky Holmes, 43 Photo credit: Becky Holmes

The release of the Netflix documentary, The Tinder Swindler, has led many people to question the legitimacy of people they meet online.

‘Simon Leviev’, whose real name is Shimon Heyada Hayut, swindled an estimated $10 million from victims across the globe whilst adopting a false persona both online and in person.

He was sentenced to 15 months for his crimes, but served only five before being released.

It seemed after this programme was aired, former victims of catfishing and romance fraud felt inspired to share their stories to raise awareness of the crime.

“I was violently sick, I could have committed suicide, just gone out in my car and rolled it over the bridge. I couldn’t eat, it was a horrible feeling.”

Sunita Brittain, 51, from Doncaster was swindled out of her life savings by a man she met online who she thought was “the love of her life”.

They met online via Facebook's dating site and the perpetrator of the crime “Michael Anderson”, 51, claimed he was the director of a multi-global engineering company.

They exchanged thousands of messages, with him referring to her as his "queen" and telling her he loved her before having met her in person.

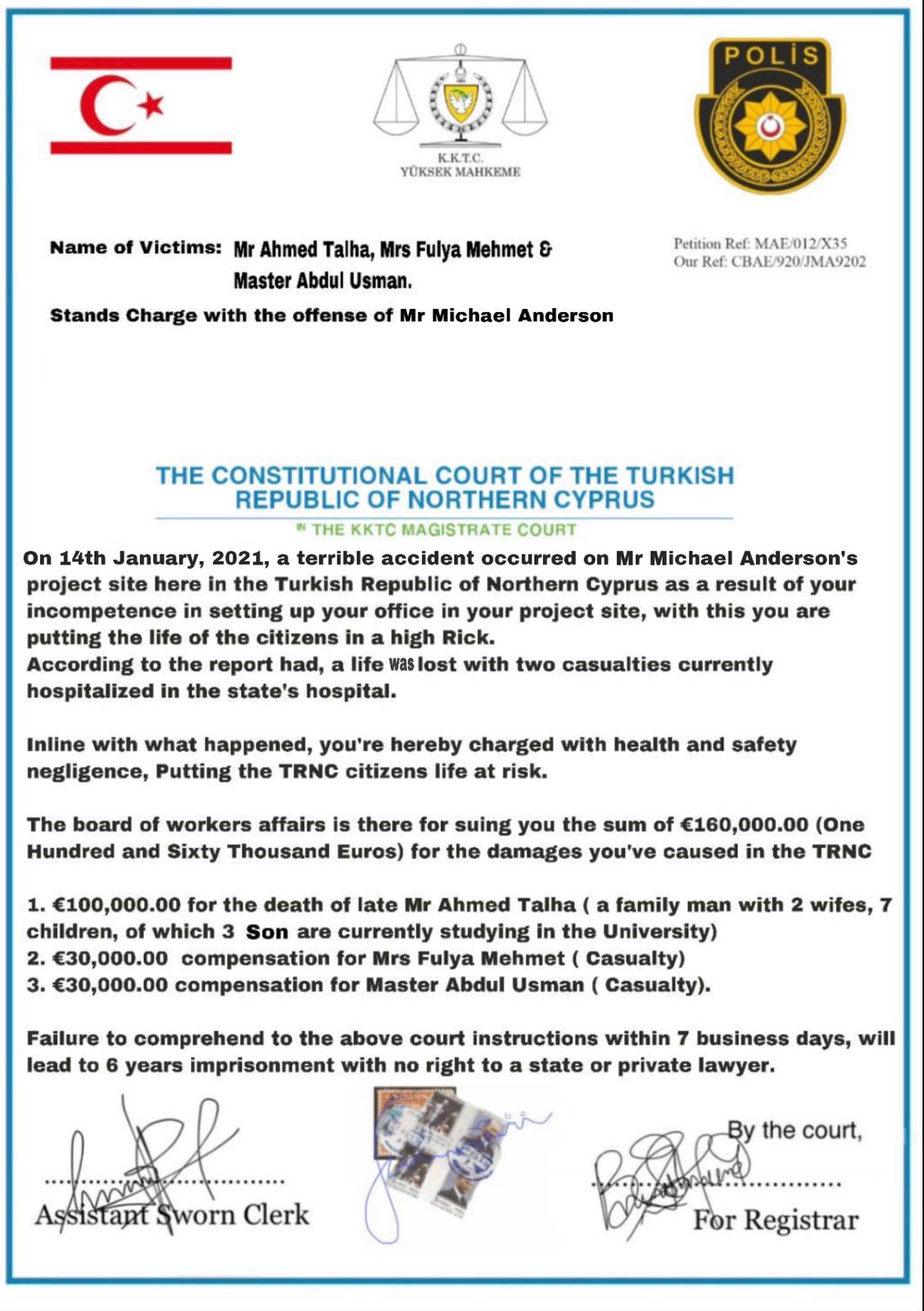

After speaking for about a month, he claimed he was “in a crisis abroad” and needed her to send him money.

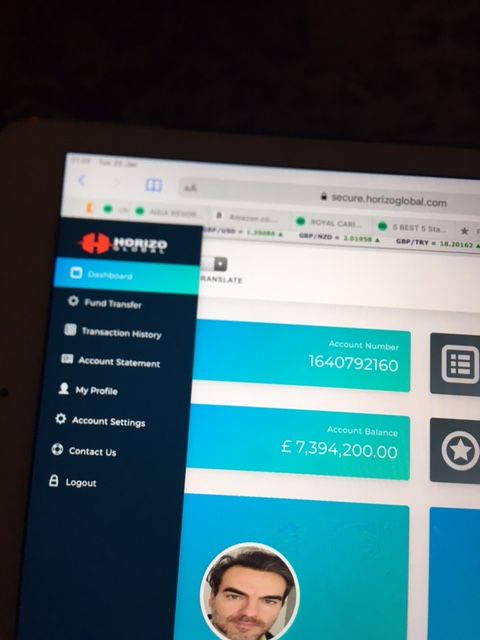

He set up a fake offshore bank account and after telling Sunita, “You are my queen. I don’t like to ask and it’s entirely up to you, but I promise I will pay you back", she felt as though she had to help him and transferred him her life savings of £9,000.

After speaking with her friend, Sunita realised the whole story was a lie and she had been scammed.

Speaking about her experience, Sunita says: “When you’re divorced, you cling onto someone. I had just come out of a 25-year marriage, I was in a very vulnerable situation.

“It’s not a lot of money to some people but to me it was my whole life savings. I felt horrible, ashamed and embarrassed.

“People don’t understand that when you’re in a very vulnerable situation, you act in a completely different way to how you would in any other normal situation.”

A picture of the fake bank account "Michael" set up, which showed his supposed funds of over £7 million. Photo credit: Sunita Brittain

A picture of the fake bank account "Michael" set up, which showed his supposed funds of over £7 million. Photo credit: Sunita Brittain

The report "Michael" sent Sunita, convincing her a crisis had happened abroad and he had been sued. Photo credit: Sunita Brittain

The report "Michael" sent Sunita, convincing her a crisis had happened abroad and he had been sued. Photo credit: Sunita Brittain

Paul Carrick Brunson, an expert in interpersonal relationships and personal development, believes self-worth plays an important role in catfishing.

When speaking about the victims of catfishing, Paul says: “Everyone on this planet wants to know that they matter.

"In particular, they want to know that they matter to someone else, because what he's done (Simon Leviev) is, especially in the first month, he makes you feel as if you matter and for a lot of these people, they all had the same thing in common. They wanted to know they mattered.”

If a person has a high level of self-worth and strong emotional intelligence, they are less likely to fall victim to romance fraud and catfishing.