Drill, Death & Dishonour

Is music the reason the kids are dying?

2020 Bl@ckbox Hardest U18s Cypher

2020 Bl@ckbox Hardest U18s Cypher

Drill. The sub-genre that allegedly carries a license to kill.

As knife crime rates across the country rise, the call for accountability intensifies. The prime suspect being drill music; the new genre of hip-hop that supposedly encourages the youth to pick up knives.

But can music be blamed for a whole epidemic of crime?

Or maybe drill is the generational punk and rock that’s turning the youth bad.

Over the last few years, as drill has risen, so has its level of scrutiny.

Replacing grime, a UK renowned garage style of rap music, drill emerged with a new style of beat and a whole new approach of lyricism. Originating in Chicago, the new trap style anarchic music was quickly embraced and endorsed in London, specifically South in 2012, before proliferating in the rest of the country.

But perhaps something makes drill more deadly than grime and other prominent UK genres.

It could be the nihilistic and braggadocio nature of the lyrics, or the enticing 808s and dark melodies. Or maybe it's the supposed ability to coerce the youth into crime.

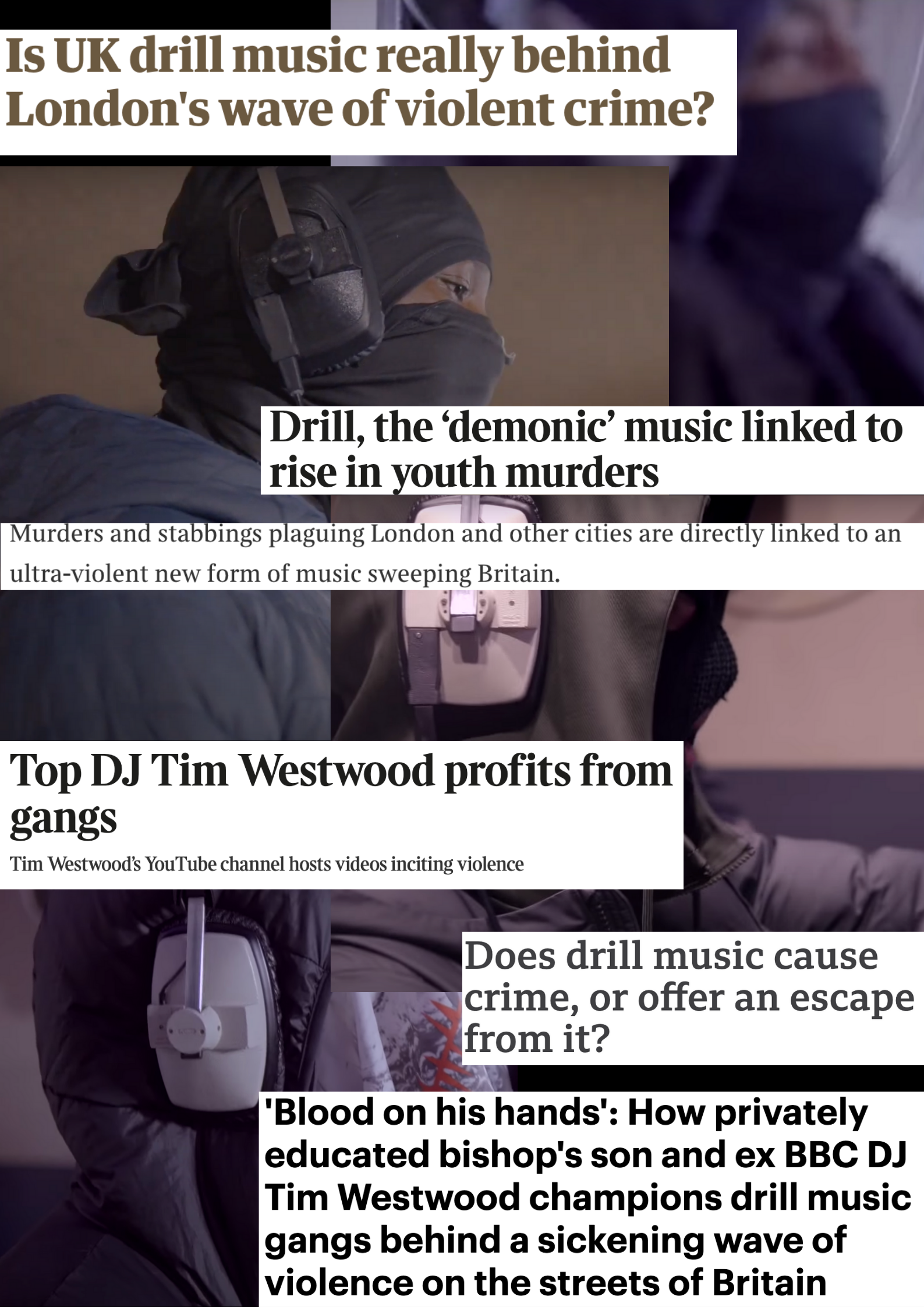

Attempts to criminalise drill have been aided by persuasive media coverage. ‘Top DJ Tim Westwood profits from gangs’, ‘Drill, the ‘demonic’ music linked to rise in youth murders’, headlined The Times. One of the 2018 articles claimed, “Murders and stabbings plaguing London and other cities are directly linked to an ultra-violent new form of music sweeping Britain.”

It's surprising that such a subjective opinion can be published by a mainstream media platform. How can society form their own understanding when headlines are blasting the same opinion, derived from street illiteracy?

Street illiteracy is a term coined by Jonathon Ilan, in The British Journal of Criminology, referring to the way British authorities misread drill and consequently react counterproductively to control crime.

Jonathan Ilan is a Senior Lecturer of Criminology at the University of Kent. With his main research interests being street culture, ethnography, youth crime and youth culture, Dr Ilan focuses on understanding and explore the variance of cultural norms in modern day society. His book ‘Understanding Street Culture: Poverty, Crime, Youth and Cool' explores the fear-fascination relationship society has with the urban poor, as well as the forms of expressivity associated with the marginalised.

Ilan believes the authorities' attempt to censor drill music is “based on a thin, ‘street-illiterate’ understanding of the genre that ultimately rests on stereotypes of young black men as violent ‘gang’ members”.

Donya Lamrhari works within the Disrupting Exploitation team at The Children's Society. She said: “With roots in disadvantaged inner-city London, drill appeals to young people who grow up in deprived areas. It is a form of expression for otherwise voiceless communities.”

In many cases, drill artists belong to the demographic: young, male, black and underprivileged, in which their music can be used to tell their story.

When growing up around non affluent surroundings, opportunities are curtailed. In addition to this, the unnecessary school exclusions black boys face, in which their white counterparts are dealt with differently, leaves young boys in a place where they are vulnerable to gang grooming.

Emily Beever is the Senior Development Officer at No Knives Better Lives, Youth Link Scotland. “The drivers of violence are really complicated. Not everyone that picks up a knife and goes on to use it has the same underlying reasons.” She said, “There’s poverty, deprivation and trauma, but there's also a lot more factors that may play a short-term role which carry longer undercurrents like, gang violence, fear or bullying.”

Therefore, the transition from this difficult lifestyle into music can not only help the individual but inspire those around them and create a fellowship for listeners.

Ilan stresses the importance of highlighting that engaging in music is more a step away from violence and ‘the roads’ than an attempt to incite and entice others into it.

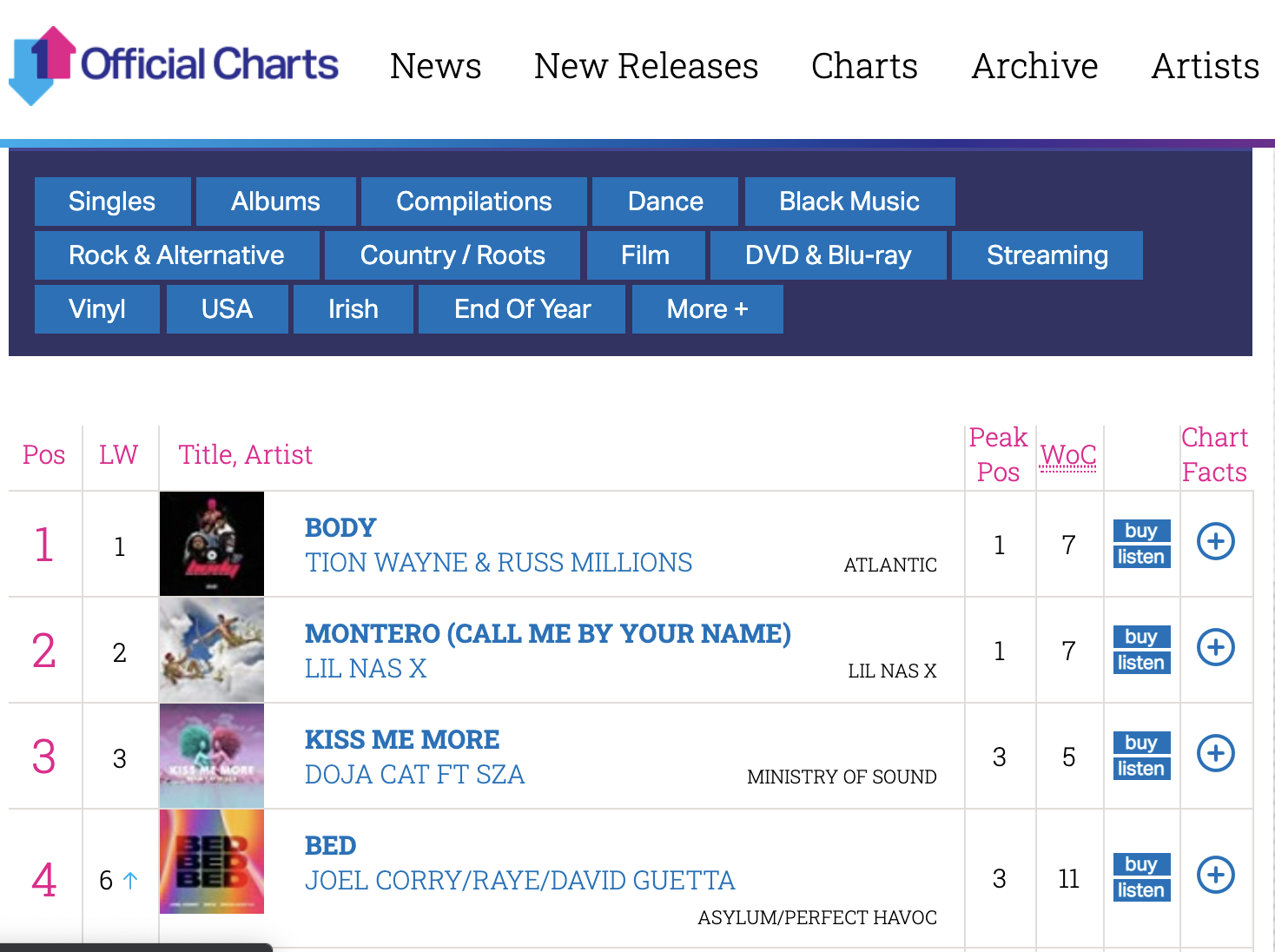

In April this year, drill rappers Russ Millions and Tion Wayne topped the UK charts with their song, Body. The first drill song to reach number one.

A viral TikTok trend and an exciting remix helped push the track through the charts to maintain number one for over two weeks.

However, not everyone was as happy to see the artists’ success.

"Soundtrack to murder: For the first time, a gangland 'drill' track is at Number One - spreading a message of hatred and violent revenge being echoed in playgrounds across the country. So why IS the BBC promoting it?"

“The young gangs of London increasingly enjoy a twisted kind of fame, and their millions of fans fastidiously follow their rivalries, chart the postcode territories, know the colours sported by each gang, and even know the estates in which the gangs operate."

“In London’s poorest areas, young boys see this form of music as a thrilling call to arms."

“It would be easy to deplore drill artists as reprehensibles who should all be behind bars. But many drill artists insist that the music has allowed them to escape gang culture"

“One thing seems all too clear; as its popularity grows, its malevolent influence will continue to spread.”

However, in response to the article, Sian Boyle, the author and Deputy Investigations Editor at the daily mail, said:

“My views on the situation, which are not necessarily the views of the newspaper, are that drill serves a place in music and banning it would be a form of censorship and against freedom of speech.

“The government should look at the socio-economic causes of knife and gun crime especially amongst impoverished inner-city black youths including funding cuts, inequality, racism, lack of role models and lack of social mobility and opportunities, before trying to ban a form of music.

“As a way to prevent any direct violence being caused by this music, platforms including YouTube should dub out lyrics which directly incite violence or gloat about death victories.

“There should also be warning labels at the beginning of songs to deter impressionable children from aspiring to the lifestyle. This would prevent incitement of violence but still allow creative freedom.”

Across the UK, as youth violence rises there is a heightened need to find the cause. Artists are being scrutinised by authorities for lyrics that might ‘incite’ or ‘glamorise’ violence, as their lyrics are held under a magnifying glass.

Loski, a UK drill legend, is renowned for building the scene to what it is today. Part of the popular group Harlem Spartans (HS), he made the genre his own with the release of Hazards (8 million views), DJ Khaled (7.5 millions views) and Teddy Bruckshot (4.5 million views) towards the beginning of his drill era in 2016 to 17.

In an interview with Zeze Mills for Trend Central, Loski claimed drill is a ‘facade’, suggesting artists are performing to what the fans want to see rather than their true reality.

Being in and out of jail had a huge impact on the young artist’s music career, as well as others in the Kennington based gang: MizOrMac, Blanco, OnDrills, JoJo, Trapfit and more.

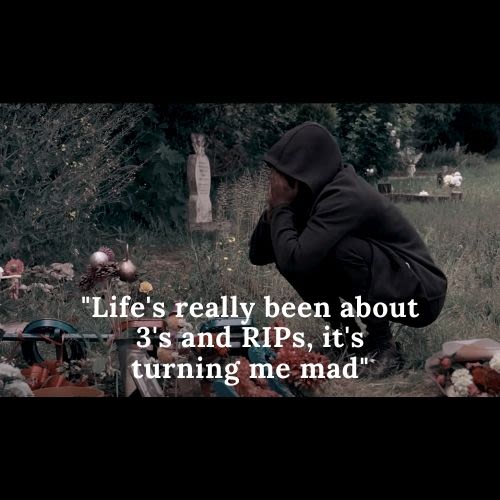

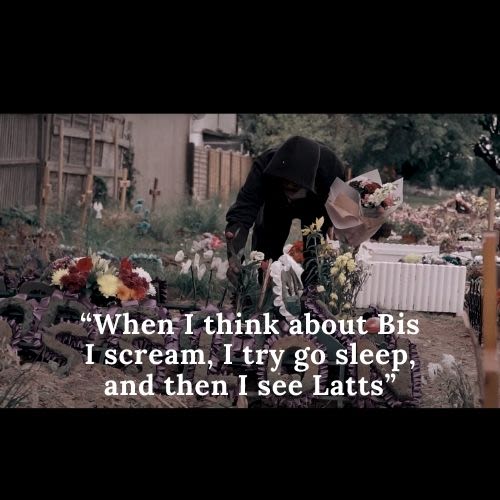

Upon MizOrMac’s release from prison, he went straight back into music. Wasting no time, on the 7th June 2020 he released ‘Return Of The Mac’, in which he refers to the loss of former friends and HS members Bis and Latts (SA).

Only 22 years old, the young rapper speaks about the effect of losing his friends whilst in prison and how it changed him as a person.

“Instead of street-illiterately adopting a hostile stance to drill, the authorities could listen deeply to it” Ilan said. “Should they do so, they would discover that the music sits within a wider ecology where there are varied attitudes to crime and violence—and where reflections on the pain of life and futility of criminality feature alongside the more numerous and obvious references to violence.”

To understand drill culture, it’s important to look much deeper than the surface, or rather the first few recommended videos on YouTube.

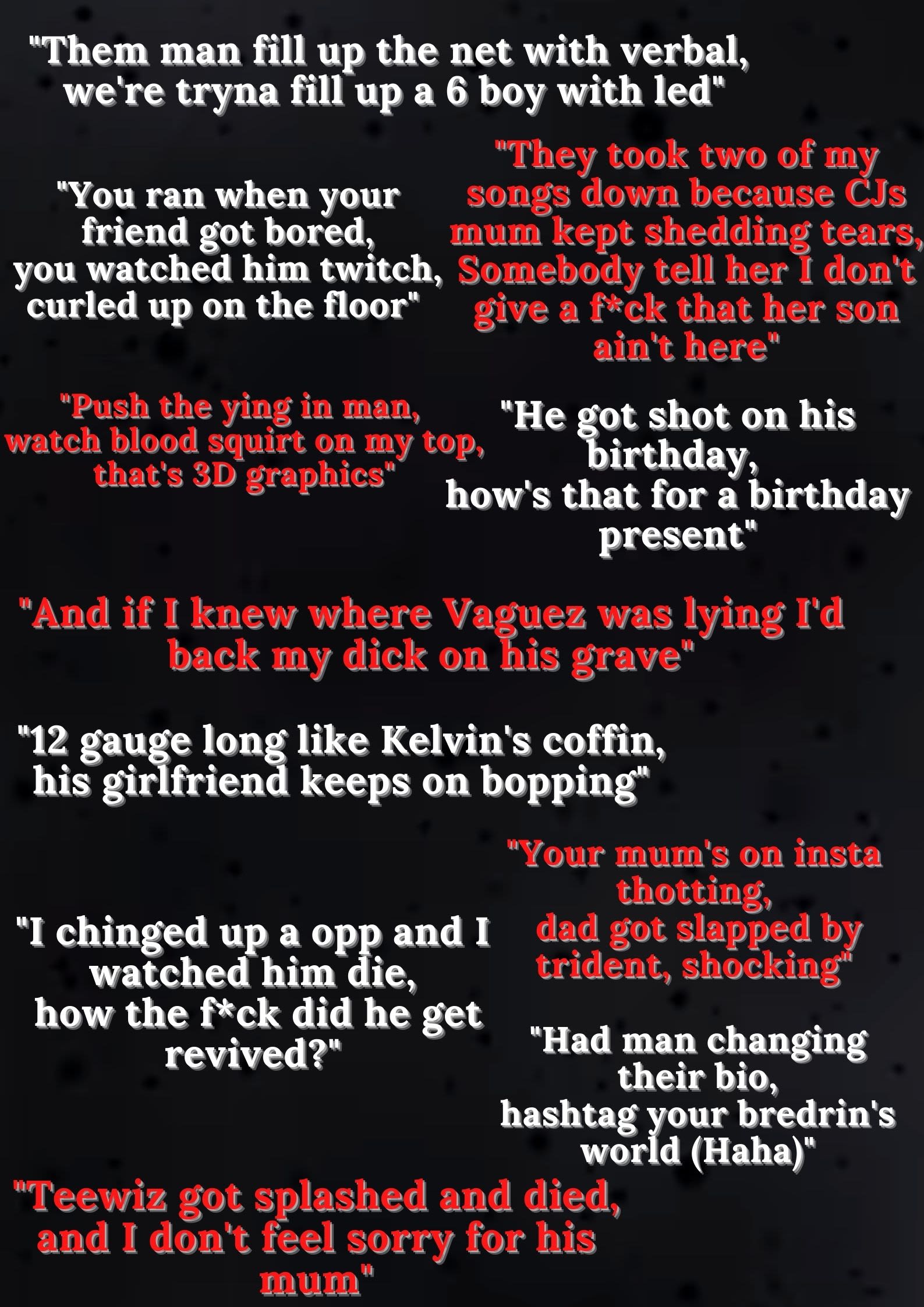

After seeing and hearing some of the shocking and largely disrespectful lyrics plastered over social media, it’s not hard to understand why the genre has earned the reputation it has.

However, this doesn’t mean that when you slap on some drill chart topping, Headie One, you’ll be driven to commit a fatal attack.

Charis Kubrin, an American criminologist and Professor of Criminology, Law and Society at the University of California explained lyrics, in ‘Gangstas, Thugs, and Hustlas: Identity and the Code of the Street in Rap Music’, as ‘discursive actions or artefacts that construct an interpretative environment where violence is appropriate and acceptable.’ However, she concludes ‘music does not cause violence.’

MizOrMac - Return Of The Mac

MizOrMac - Return Of The Mac

MizOrMac - Return Of The Mac

MizOrMac - Return Of The Mac

MizOrMac - Return Of The Mac

MizOrMac - Return Of The Mac

Drill music is heavily criticized in the media for the way it is dominated by violent lyrics and taunting mannerisms. Ra’Siah, a 22-year-old Sheffield rapper, watched as drill took over his city, dominating studios as the primal sound. Just like a trend he saw fellow artists become ‘driller’s, fine-tuning wordplay and flows to adhere to the new popular sound, even if it had no relation to their reality.

The extent some artists go to reach the ‘shock factor’ Ra'Siah described as ‘sickening’. “It’s like they’ll say the worst thing they can think of and pretend that's what they're on.”

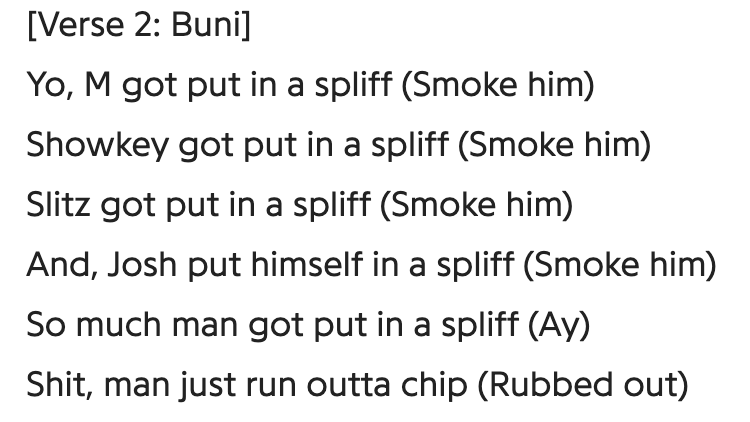

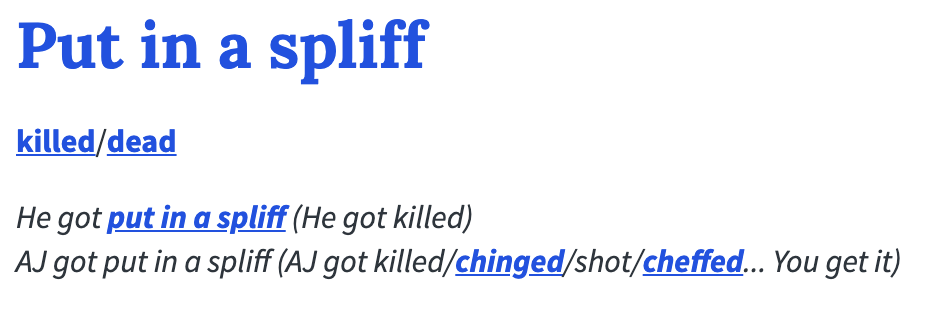

For example, as seen in the previous video, the tragic loss of 16-year-old Showkey, as well as his associates Slitz and MDot. In 2020, Russ Millions released 'Out of Order', featuring Buni, in which Buni relentlessly mocks all three of the young boys’ deaths, using the ‘put in a spliff’ metaphor.

Ra'Siah - Sheffield Artist

Ra'Siah - Sheffield Artist

Out of Order - Russ Millions (feat. Buni, Turner & E1) - Genius

Out of Order - Russ Millions (feat. Buni, Turner & E1) - Genius

Urban Dictionary definition

Urban Dictionary definition

Shocking drill lyrics

Shocking drill lyrics

Desensitization in the streets

An anonymous interviewee has recently been not guilty for a murder, following a case in which an 18-year-old died from a severe knife wound.

“I don’t know if it’s from drill or just how life is now but, on the roads, you’re desensitized to it. You’ve got to be.” he said. “I’ve been shot at, stabbed, been jail, and I’m still here, this shit ain’t a joke though.”

“I feel bad for his family, but not for him.”

“I like how the music is because it talks about what I’m living. Most these people wouldn’t know about this life if it wasn’t for music. Music doesn’t make people do these things, it’s just something some of us can relate to and it sounds good so other people listen too.

“Anyone who thinks music creates violence is stupid. There was violence way before drill existed and it’ll be the same when a new wave genre takes over. Them politicians are just looking to blame anything that's not themselves.

“They really think if they silence us the violence will stop? Like they think these guys can only communicate through YouTube, when you delete their videos, they’re just gonna be like ‘aight we’ll allow it then."

The use of slang is often perceived by authorities as code that rival gangs use to communicate and taunt each other online. The Metropolitan police use the unit, Trident, to monitor music on YouTube. Anything they believe incites violence they will ask to be removed. But in a genre characterised by violence it's difficult to decipher what is classed as inciting.

“The real violent guys aren’t sending on YouTube; they're firing in real life. Feds know where to look but they’d rather look in the wrong place."

Rio Rainz - Bl@ckbox

Rio Rainz - Bl@ckbox

So, if drill is the weapon that is stealing so many lives, why hasn't it been taken off the streets?

A spokeswoman for the Metropolitan police force’s major crime unit, Rebecca Byng, described Criminal Behaviour Orders (CBOs) as a vital device to “steer young people away from violence”. She said: “We are not targeting music artists but addressing violent offenders”.

Introduced in 2014, CBOs are ultimately used to monitor convicted criminals in attempts to prevent future criminal activity.

So how are these ‘violent offenders’ being addressed?

In January 2019, popular drill duo Skengdo & AM made history by receiving the first ever prison sentence for performing a song. The pair were given a nine-month sentence, suspended for two years, for performing their song Attempted 1.0 at a London concert.

Jonathan Ilan refers to Skengdo & AMs punishment as ‘uncomfortably jarring in a society that largely assumes freedom of speech and artistic expression.’

Prior to this, London rap group, 1011, received a CBO which actively censors all of the music they can perform and release.

In 2015 drill pioneer Digga D, and associates TY, Sav’O, Horrid1 and Mskum formed 1011, named after their West London postcodes. The group grew a large audience in 2016 with their popular releases: Play for The Pagans, No Hook and Kill Confirmed, all of which have since been removed from YouTube and re-uploaded by fans.

A year later in November 2017, amidst their growing popularity, 1011 were arrested following a search which found them in possession of machetes, baseball bats, masks, balaclavas, and gloves.

Before their guilty plea they had told police they were using the weapons as props for a music video rather than what police believed to be an attack on rival gang, 12world.

In addition to their sentencing, 1011 received a CBO. CBOs were introduced in 2014, ultimately to keep an eye on convicted criminals in attempts to prevent future criminal activity. 1011s case was the first time a CBO had been used to censor music.

The gang were told they must obtain permission from the MET before releasing any music, they were not allowed to mention London postcodes or reference any real-life incidents or people. A breach of this could send them back to jail. Four of their previous videos were also removed from YouTube after reaching a collective of over 10 million views.

Following the issuance of the CBO, campaign group 'Index on Censorship' condemned the order. Chief executive, Jodie Ginsberg said: “Banning a kind of music is not the way to handle ideas or opinions that are distasteful or disturbing”, stating there should not be a “precedent in which certain forms of art which include violent images or ideas are banned.”

She said: “We need to tackle actual violence, not ideas and opinions.”

In 2018 1011 started a petition to stop police from banning their videos from YouTube.

Tweet from AM before the sentencing

Tweet from AM before the sentencing

Detective Superintendent Mike West said the number of videos that 'incite violence' has been increasing since 2015.

“The gangs try to outrival each other with the filming and content – what looks like a music video can actually contain explicit language with gangs threatening each other,” he said. “There are gestures of violence, with hand signals suggesting they are firing weapons and graphic descriptions of what they would do to each other.”

He insisted only videos that 'raise the risk of violence' are flagged.

A spokesperson for YouTube said: “We have a dedicated process for the police to flag videos directly to our teams because we often need specialist context from law enforcement to identify real life threats.

“Along with others in the UK, we share the deep concern about this issue and do not want our platform used to incite violence.”

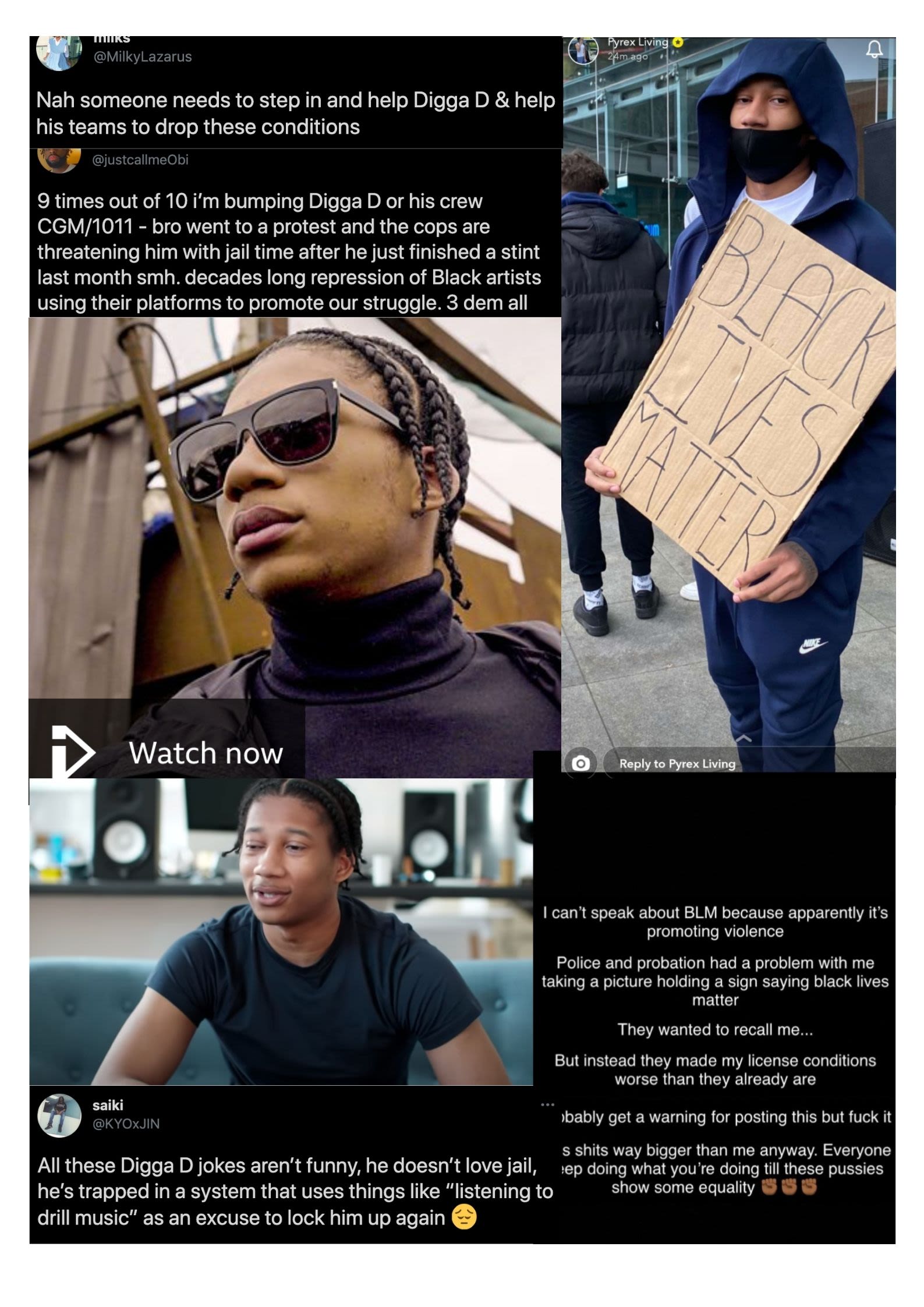

Only 20 years old, Digga D has been to jail five times and says he is constantly on edge about returning due to the intensified restrictions of CBO.

The young rapper not only has a GPS tracker attached to his ankle, but he is also made to check in with probation every three hours. Upon every music release, Digga and his lawyer, Cecilia Goodwin, must rigorously check through his lyrics line by line to ensure there is no risk of breach which could send him back to jail.

Memes and tweets circulated suggesting he ‘loves jail’, making a joke of the rapper's frequent recalls and understandably frustrating the artist.

Tweets about Digga D being recalled to jail

Tweets about Digga D being recalled to jail

After the release of BBC’s Defending Digga D, people began to understand the gravity of his situation.

“The documentary put drill on the map to a wider audience” Cecilia said, “People who didn't know anything about the world that he lives in and comes from now have an insight. It opened up a lot of eyes, ears, and doors.”

Digga also explained via snapchat that he had been threatened to be recalled after taking a picture at a BLM protest. “I can’t speak about BLM because apparently it’s promoting violence” he said. “They wanted to recall me… But instead, they made my licence conditions worse than they already are. Probably get a warning for posting this but fuck it.”

BBC Defending Digga D documentary

BBC Defending Digga D documentary

Digga D tweets

Digga D tweets

“Marginalizing the excluded further, video removals and restrictions on performance are shown to be counterproductive from a crime-reduction perspective.”

The attempt to ban or censor drill is perceived as feeding into the pre-existing systemic racism in which authorities are so oppressive, they can’t bare to see artists succeed by legitimate means.

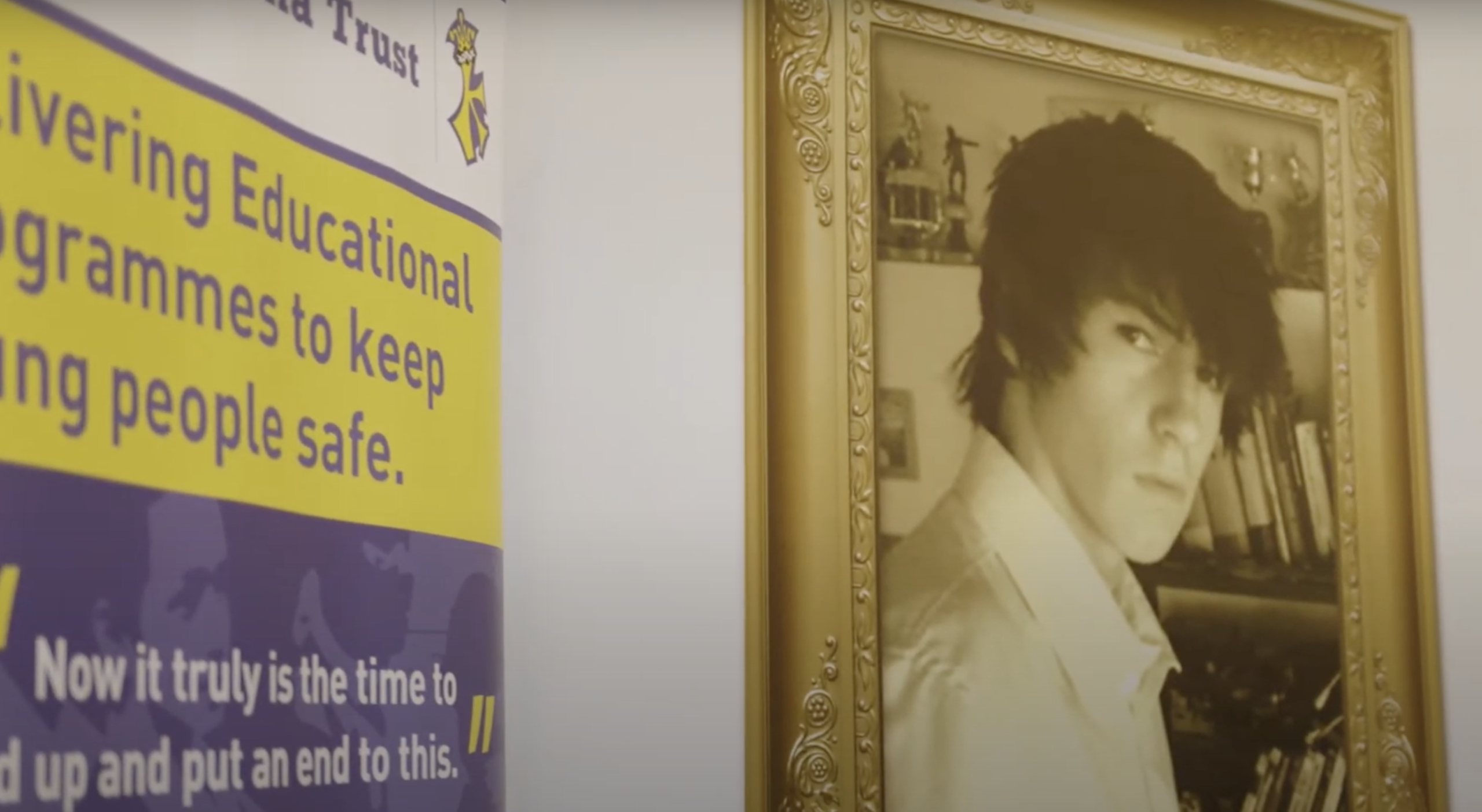

The Ben Kinsella Trust

The Ben Kinsella Trust

In 2008 the Ben Kinsella Trust was set up following the tragic, unprovoked murder of 16-year-old Ben Kinsella. Prior to his murder, Ben had been a campaigner for youth violence. He had written to the prime minister at the time challenging the government on what they were doing to tackle youth violence. He believed the world was unsafe for teenagers and not enough was being done at a high level.

The Trust was set up to campaign for justice and action for those affected by knife crime and to educate young people about the dangers of carrying knives.

Patrick Green, CEO of the Trust, said: “Art is art and violence is violence. We need to respect music for what it is as a social commentary. There is a difference between a social commentary and drawing people into violence.

“When I was growing up punk music was demonised. Youth culture reflects the time, it's a social commentary and we’ve got to accept it as that. There’s always been violence in music.

“While we’re all agonising about drill music, it’ll fade away like grime did in the next few years to be replaced by something else. However, there is a line between art and using music to exploit people or antagonise. It can be a difficult line to find in art, but it is one that we’ve got to recognise.”

Based in Islington, Barking and Nottingham, the Trust offers lesson plans and workshops to educate young people on the dangers of knife crime and encourage them to stay safe.

“We’ve created an exhibition which is a series of rooms built on the lived experience of people who have been affected by knife crime. The young people travel through the rooms we’ve created and make a series of choices which lead them in different directions.

“It’s based on not just the victim's journey but the offender's journey as well. It helps you unpack what one single decision might lead to and the number of people that might be involved that you might not have associated.

“Youth crime is a multi-layered problem. You start with the fact we have an unequal society with wealth distributed disproportionately. We have inequality, deprivation, poverty, and racism. We don’t have enough resources targeting young people, particularly around mental health. And then you layer that on with gangs who are very good at exploiting vulnerable young people."

“We recognised very early on that despite all our efforts and anybody's efforts in tackling knife crime, no one single person or one single organisation can solve this very complex issue.

"Collaboration is the only way forward.”

I contacted the Metropolitan for a statement on what they are currently doing to reduce knife and violent crime in the UK. I was told they did not have time to answer.