Getting to grips with gaming addiction

Ever find yourself chasing high scores way past your bedtime? It's about time we look into why it's sometimes hard to put down the controller.

Anthony could see it coming. It was pitch black and his eyes felt heavy. He opened all the windows and turned up the radio - the empty roads were filled with the deafening blast of heavy metal. His throat hurt from screaming at himself in a desperate attempt to stay awake. He knew he had to find somewhere to pull over within the winding, country roads.

It wasn't enough.

As Anthony slept, the van hurtled past the bend into the opposing lane of traffic, then powered straight through a row of bollards. The front of the vehicle folded in half like a piece of paper as it smashed into an embankment. Anthony's relaxed legs popped out from underneath the dashboard - saving them from being completely crushed.

It wasn't until he woke up hours later, as paramedics deployed a crane to pull him from the wreckage, that he realised what had happened. As he waited in the hospital, somehow miraculously unscathed, he knew what he needed to do. He needed to stop playing World of Warcraft.

"I played it for about a year and had to go cold turkey. Far too many hours were being absorbed by it. My business was suffering. My life in general was non-existent.

"I even had what I called a WoW beard. It was this huge uni-bomber style beard which was from sitting there playing hours and hours of Warcraft instead of going out socialising."

It's stories like Anthony's that pushed the World Health Organization in September last year to classify gaming addiction as a genuine, mental health condition.

"Gaming disorder is defined as a pattern of gaming behaviour characterised by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences."

Whilst this definition does match Anthony's behaviour, what it doesn't do is answer the question of why people are getting addicted to games in the first place.

For 40-year-old Anthony, his addiction has always been about the social aspects of gaming, and he still experiences that today - 14 years after his accident.

Of course, the video game market is full of hundreds of different titles - from the infamously popular dance moves of Fortnite's online battle royale, to the italian antics of Nintendo's platforming plumber duo Super Mario Bros, and even cowboy adventures in Rockstar's immersive Red Dead Redemption - so it's unclear exactly why certain people get "addicted" to specific titles.

We sat down with Greg Westerman-Hughes, a PhD researcher from the University of Lincoln looking at the psychological basis behind video game addiction, to find out why people play and which titles make it the most difficult to turn off the power.

Are video games designed to be addictive?

So according to Greg, video games themselves are not to blame, as the addiction stems from the needs and wants of individual gamers.

What isn't clear is how video games play into those needs, and whether that is something considered during development.

According to independent developer Ben Sutcliffe, from Sheffield's NoSkyVisible, making video games is all about putting the love and care into designing something that people can't wait to play.

"Generally, all the people I speak to just want to make excellent games. They want to make awesome experiences for people. They want to be creative. It isn't about the money, it really isn't."

Looking into loot boxes

Loot boxes are the latest in gaming controversies. They contain in-game items like armours and weapons, and can be earned by simply playing the game or spending real-world money.

The contents of a loot box are completely random, so players buying them have no idea whether they'll get the item they really want (like a powerful gun capable of easily defeating other players) or something completely useless to them (for instance, equipment for a character they never play as).

They feature in different video games across the market, including Star Wars Battlefront 2, Injustice 2, Overwatch, Apex Legends and Fortnite.

The loot box industry is predicted to be worth $50 billion by 2022, according to Juniper Research. They have been banned in several countries worldwide, such as Belgium and the Netherlands, due to their similarities with gambling.

A report published by the UK's gambling commission concluded that there isn't a link between loot boxes and gambling, although their data does show that 31% of children aged between 11-16 have opened one.

As a software engineer from Sky Betting and Gaming, and a video game developer hobbyist, Will White sits at the crossroads between gaming and gambling. His own opinion is that there is definitely a link between the two:

"I do see loot boxes as a style of gambling because you have a goal you might want. It will be a card, a skin, a rare weapon...

"You put the money in, you don't know whether you're going to get it, and it's essentially the thrill of the pull of the lever as to whether you get what you want.

"I personally think the distinction between that, given that you'll always get something back but it might not be what you want, and the distinction between gambling where you might not get anything back at all, is broadly meaningless because it's the action that people become addicted to."

We surveyed 20 gamers anonymously to get their opinions on loot boxes. Despite the huge amount of revenue they allegedly generate for the video game industry, 70% of respondents said they didn't buy any loot boxes at all.

Will isn't the only expert who believes there just might be a link between loot boxes and gambling.

Dr David Zendle, a computer science lecturer from York St John University, is one of the world's leading experts in loot boxes. He has been discussing their relationship with gaming disorder at the Government's newly established Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee.

We sat down with Dr Zendle to ask him about the potential links he's found between "problem gamblers" and loot box spending whilst completing his research, as well as what he believes might be next step towards regulating these practises for safer gaming.

Gaming addiction conversations should stay grounded

Let's not let the conversations get out of control and focus on what's important

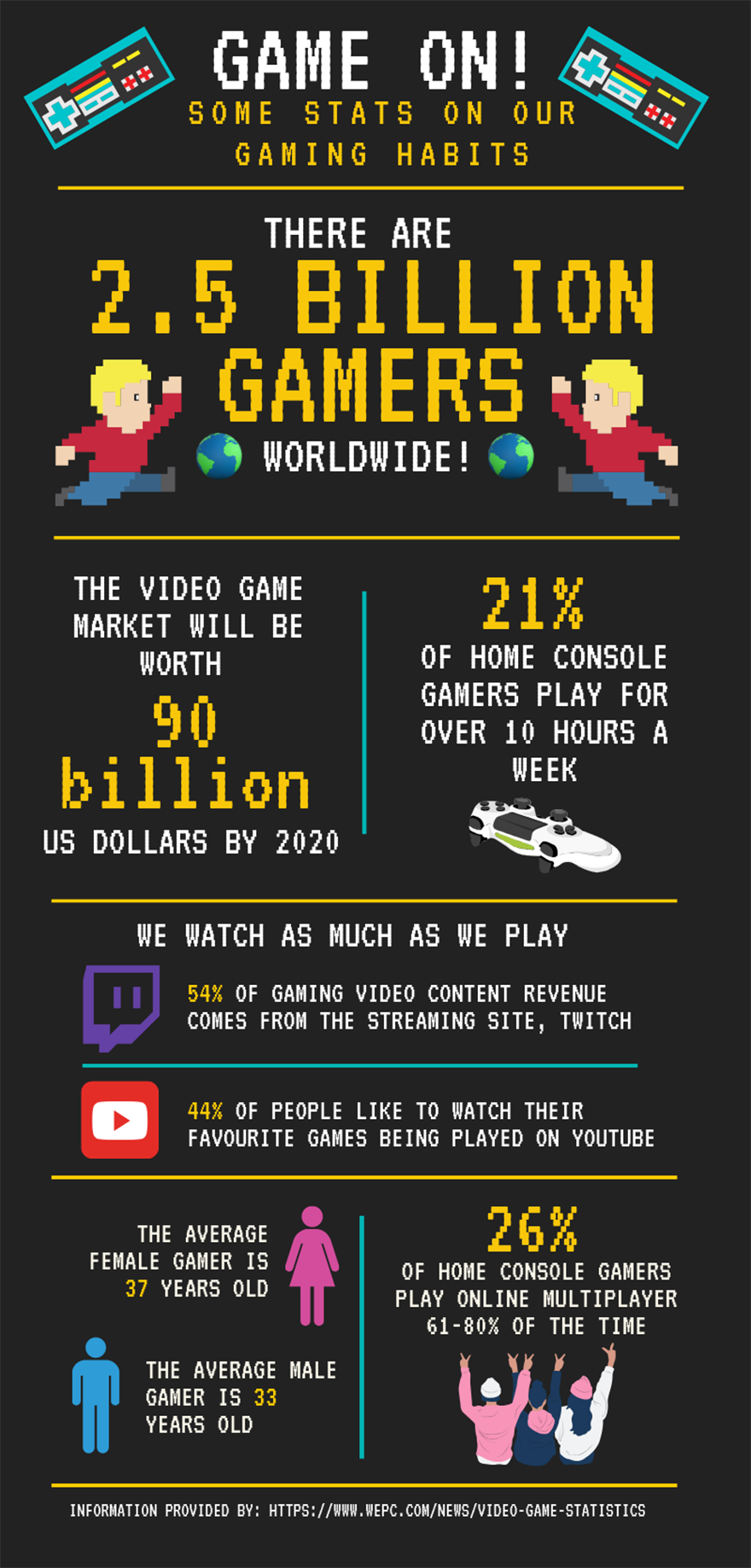

Whilst we definitely do need to discuss gaming addiction and the issue it presents for the industry, it's also important to remember that literally billions of people play games on a daily basis without harm.

Cases of video game addiction affect the minority, not the majority. In fact, there are lots of benefits and uses video games provide the world.

PhD researcher, Greg Westerman-Hughes, said that: "There are games that do socialisation, they teach and encourage certain individuals to learn different things in academia, they are called games for learning. Works very well for kids, works very well for individuals who struggle to read.

"Virtual reality is one of the big things that is being pushed now, and used as a means of training and getting people used to things. It's been used in therapy and treatment sessions for phobias and social anxiety."

"Games are art in my opinion, and art is a creative expression. Nobody should be limited at all."

What does need to be encouraged when it comes to the discussion of video game addiction, according to Dr Zendle, is getting developers to communicate with academics to learn more about this issue - as right now this isn't happening:

"Developers in general are very reticent (withdrawn) when talking to academia, because academia has come from a position of attacking games development.

"For many, many decades video game academics have basically been saying to industry your products are going to make children go out and shoot one another, and now we have a solid literature on that and it looks like those effects just don't happen. It isn't a thing."

With increased inquiries into video game addiction there is a risk of further regulation of the gaming industry, without the input of game-makers themselves.

Dr Zendle said: "The only way that really good regulation occurs is when everyone is informed by everyone else - so when academics are talking to industry to understand their practices best, and when industry is talking to academia to understand what features of what they're building might be doing to people.

"If that kind of conversation doesn't happen, I can't see any optimal regulation occurring - one that takes into account both the needs of academics and regulators, and the needs of developers when it comes to building their products.

"It'll be destructive to everyone if some kind of dialogue doesn't happen soon."

(Special thanks to Bensound.com for providing royalty-free music in some of the videos within this feature.)