How can we stop disadvantaged children falling further behind their peers after Covid?

Children from lower-socio-economic backgrounds, SEN children and girls are among the worst affected groups

Children from lower socio-economic backgrounds, those with special educational needs (SEN), and more surprisingly, girls, have been most adversely affected by the pandemic in their schooling, according to recent findings.

Some Y7s are starting secondary school with a reading age as low as six. After years of lockdowns and restrictions on socialising, combined with an ongoing cost-of-living crisis, we are only just beginning to see the educational and social impact this has had on young pupils. Even though literacy rates are starting to return to pre-pandemic levels, the ‘disadvantage gap’ in children's academic and social development has widened.

David* spoke about how his nine-year-old son, who has autism spectrum disorder, was affected by lockdown.

“He was just beginning to open up to other individuals. Within the constraints of the classroom, he was starting to get it. Then everything shut down.”

Teachers, particularly those working in deprived areas, have seen first hand how low income families are finding it difficult to support their children academically. Deputy Head of a Sheffield Primary School, Jennie Camps, said: “Parents are struggling to even buy books. Some families don’t have paper and pens.”

But how has it got to this stage, and what can be done about it?

“I had so much less time for my son when he needed me most”

The Digital Divide

The pandemic meant that teachers had to quickly adapt to online learning, but the inequalities in internet access, as well as the level of attention parents could give to their children's learning, has put some children at a disadvantage.

Deputy Head Mrs Camps says: “The government gave some laptops and other devices out, but there was a bit of a delay in getting them. We tried our best to address that by lending out all the laptops that we had in school, but it was definitely tricky.”

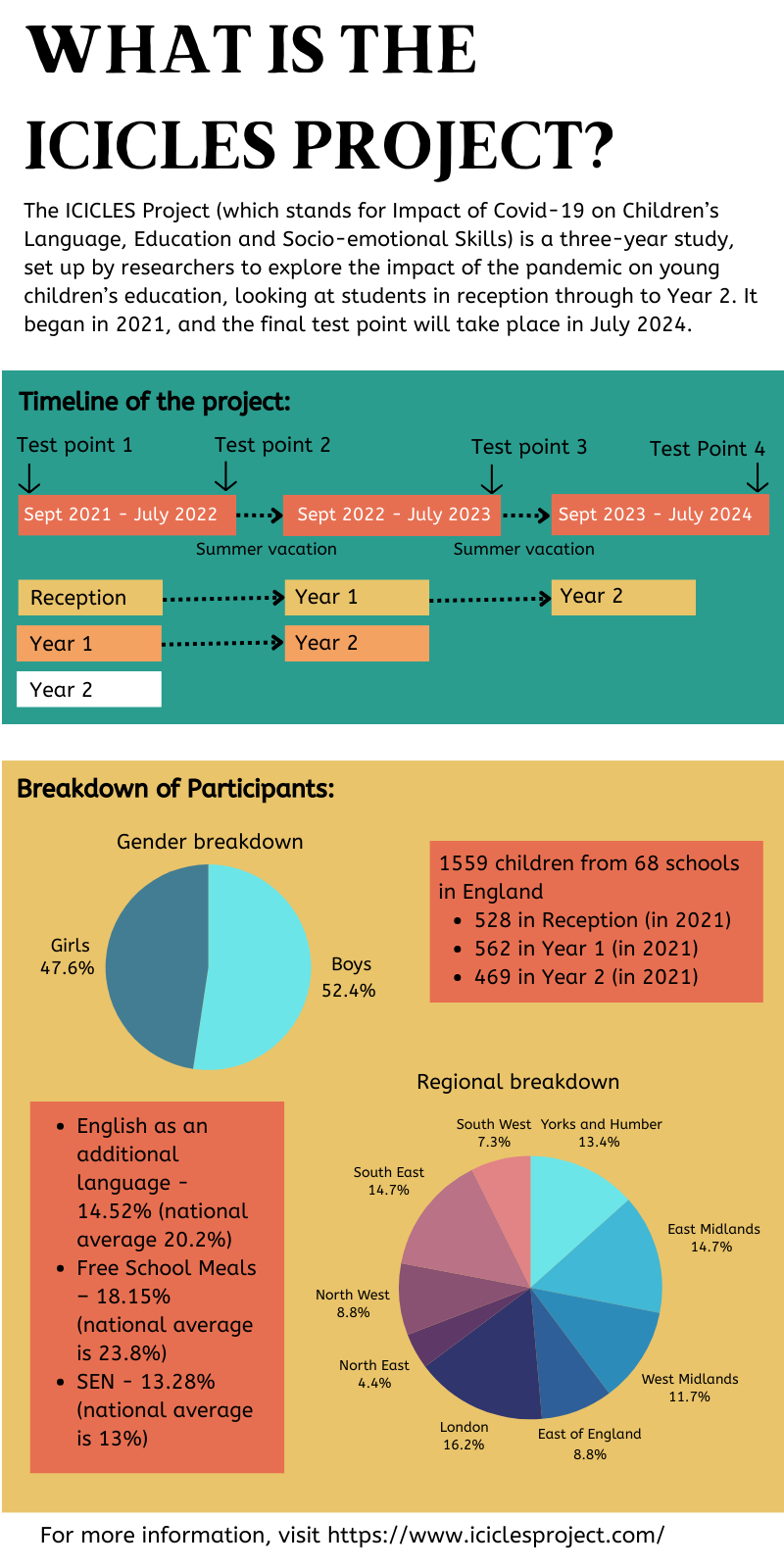

Prof Claudine Bowyer-Crane is a Professor of Education at the University of Sheffield and Principal Investigator of the ongoing ICICLES Project, which was set up to explore the long-term impact of the pandemic on children’s literacy, social, emotional and educational development over the course of three years.

“The digital divide meant that some children didn't have access to the tools that they needed to engage with learning at home, and so some children effectively missed more schooling than others. Perhaps they didn't have a laptop or there was only one laptop between several children,” she says.

“Some families could access specialist help like tutors, or put some specialist support in place, but not all children have that luxury, and so the inequality persists.”

Many parents also struggled with having to balance working remotely and home-educating their children. While his wife works as a hospital paediatrician, David* is a university reader, and had to spend a lot of time adapting his course content to online teaching, meaning he had less time to supervise his autistic son.

“I had so much less time for my son when he needed me most,” he said. “I felt guilty about this. He was often left to his own ends, and became quite addicted to video stimuli.”

Before the pandemic, David’s* son spent time reading and doing outdoor activities, but his dependence on his devices, which emerged during lockdown, made him less interested in reading, and less willing to leave the house.

SEN children have “greater levels of need”

Deputy Head Mrs Camps believes that the lack of socialisation during the pandemic had a greater impact on SEN children.

“More children are coming in with greater levels of need, and we think that that's probably because of the impact of having to wear masks, not being able to see people's facial expressions or having a wide range of people talking to them,” she says.

Dani Boden is Assistant Special Needs and Disability Coordinator at The Park Community School, a secondary school in Barnstaple, Devon. She believes that the pandemic prevented more children from being diagnosed, as well as getting educational health care plans (EHCPs), before starting secondary school.

“We’re finding that lots more children are coming up without these plans, which in secondary school is really challenging.” she says.

“It's much harder to get a picture of a child when they're spread between 10-15 teachers, whereas the primary school it's one base, one classroom, one teacher.”

Mrs Camps adds: “A lot of children really do start to struggle when they hit Year Five and Six, when the curriculum starts getting much more demanding towards secondary school. When it gets to Year 5 and 6 and a child starts having issues, we need to get it assessed quickly, so that we can send them off to secondary school with that diagnosis.”

Dani Boden discusses the pressures on teachers and the difficulties children face in the aftermath of the pandemic

Dani Boden discusses the pressures on teachers and the difficulties children face in the aftermath of the pandemic

"We need to move away from the ‘catch-up’ narrative and think more about meeting children where they are"

Girls are worse off than boys

In some cases, the pandemic has actually reversed common patterns within children’s education. Despite the longstanding trend of girls outperforming boys during primary school, so far the findings of the ICICLES project suggest that girls have been more adversely affected by the pandemic than boys.

Prof Bowyer-Crane, who is leading the project, says she is unsure of why this is the case.

“It may be something to do with girls relying more on the structure in the routine of school and maybe boys were better able to adapt to the situation. We will need to do a lot more analysis.”

Despite this, Ms Boden says that this research is less surprising from an SEN perspective, but it is unclear whether this has worsened after the pandemic.

“We see a clear gap. Boys are so much quicker to be diagnosed than girls. All the stereotypes around ADHD are based on boys, when in girls it presents very differently. Girls are very good at masking – they may go home and have meltdowns, but we don't see it at school. It can also be misdiagnosed or completely go under the radar.

“That has been a long-standing thing in terms of special educational needs, so I don't know how much that will have changed post pandemic.”

How should we support children?

Many schools, including Mrs Camps' school, have arranged for speech therapists to come and support children, while some local councils, including Devon County Council, have started to employ Education Key Workers to go into children’s homes to support them in eventually returning to school.

Ms Boden says: “I think if I was a child, I’d find [returning to school] really hard, and then obviously if you've got children with additional needs on top of that and it makes it even more challenging again. I can imagine it was quite an abstract concept for younger children.”

According to David*, “it was like the first day of school all over again” when his son returned to school after lockdown. Despite his social skills taking a “big hit” after the pandemic, his son has made more progress and has a steady group of friends, some of whom are also neurodivergent.

Prof Bowyer-Crane is critical of the push to make children ‘catch-up’ with lost learning.

“I think we need to move away from the ‘catch-up’ narrative and think more about meeting children where they are, and helping them to develop at a reasonable pace that suits them.

“Those children have gone through an unprecedented experience, so how realistic is it to ask teachers to bring those children to a level commensurate with pre-pandemic learning when they've had such a shock to the system?

Deputy Head Mrs Camps says: “There’s no acknowledgement really that this was massive for everybody, but it's vital that you do talk about that and you acknowledge that it has had an impact. You can't do the work you need to do to support children who have suffered, and are suffering, when you don't talk about it."

*David’s identity has been made anonymous.