Locked out and left to grieve

Meet the families who feel they are the forgotten victims of the pandemic, punished for the crime of love.

“Our children are grieving for parents they have lost, though they have not died,” a mother tells me, while five women nod in sympathetic agreement.

Though the group’s children vary in age from newborns to 20-year-olds, they say they have all been distressed by the loss their families have endured for the last 12 months, and for many of them, there is still no light at the end of the tunnel.

“Is Daddy going to die?” one mother’s daughter asks when she wakes up frightened in the night. Unable to see her dad, the young child worries she will never see her father again, explains her concerned mum, Vix.

Another of the women, Adele, finds her toddler similarly struggles to understand a family member is not permanently lost to them.

She said: “Yesterday he saw a photo of my partner on my phone and asked where he has gone, but then answered the question and said, 'he is gone'.

“I had to tell him he always comes back.”

With the loss of her husband, Adele also grieves for her seven-week-old son, who has never met his father.

Like Adele, whose partner was arrested when she was 12 weeks pregnant, each of these families have a loved one in prison.

While the nature of imprisonment involves a division, these women say the government’s management of prisons during the pandemic has further torn families apart.

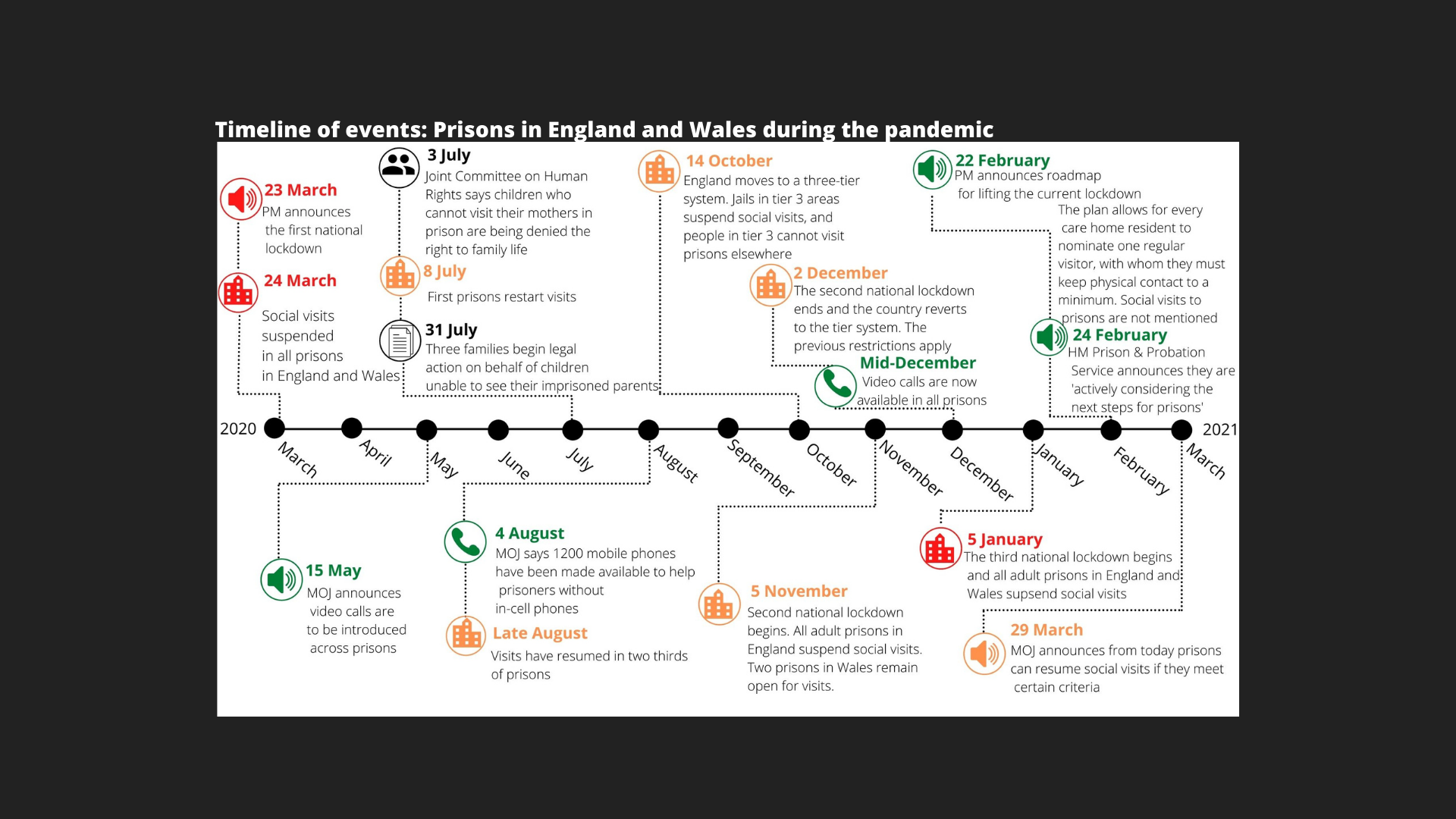

Where before social visits enabled loved ones to stay connected, the current suspension of visits in 70 per cent of prisons in England and Wales has denied families their previous regular contact.

The restrictions follow months of closures in 2020, which has prevented thousands of children from seeing their imprisoned parents for over a year, according to new research from the University of Oxford.

Dr Shona Minson, who claimed the study was the most difficult she has ever completed, found children’s mental health has deteriorated as a result, with many experiencing depression, eating disorders, and self-harm.

Families say they are struggling because they have not only been locked out from loved ones but locked out of their lives.

“My job as a mum is to protect my children; I’d lay down my life for my children. It absolutely breaks me inside that I can’t protect them from this,” says mum-of-three, Michelle.

She believes social visits are fundamental in ensuring families maintain strong relationships: “When someone goes to prison you are grieving for that loss in the house, the person that is no longer there, but there is the hope that you can go and see them for a couple hours.”

For her family, they also offered the only means of visual communication. So when visits were suspended in March 2020, her children did not see their father for five months.

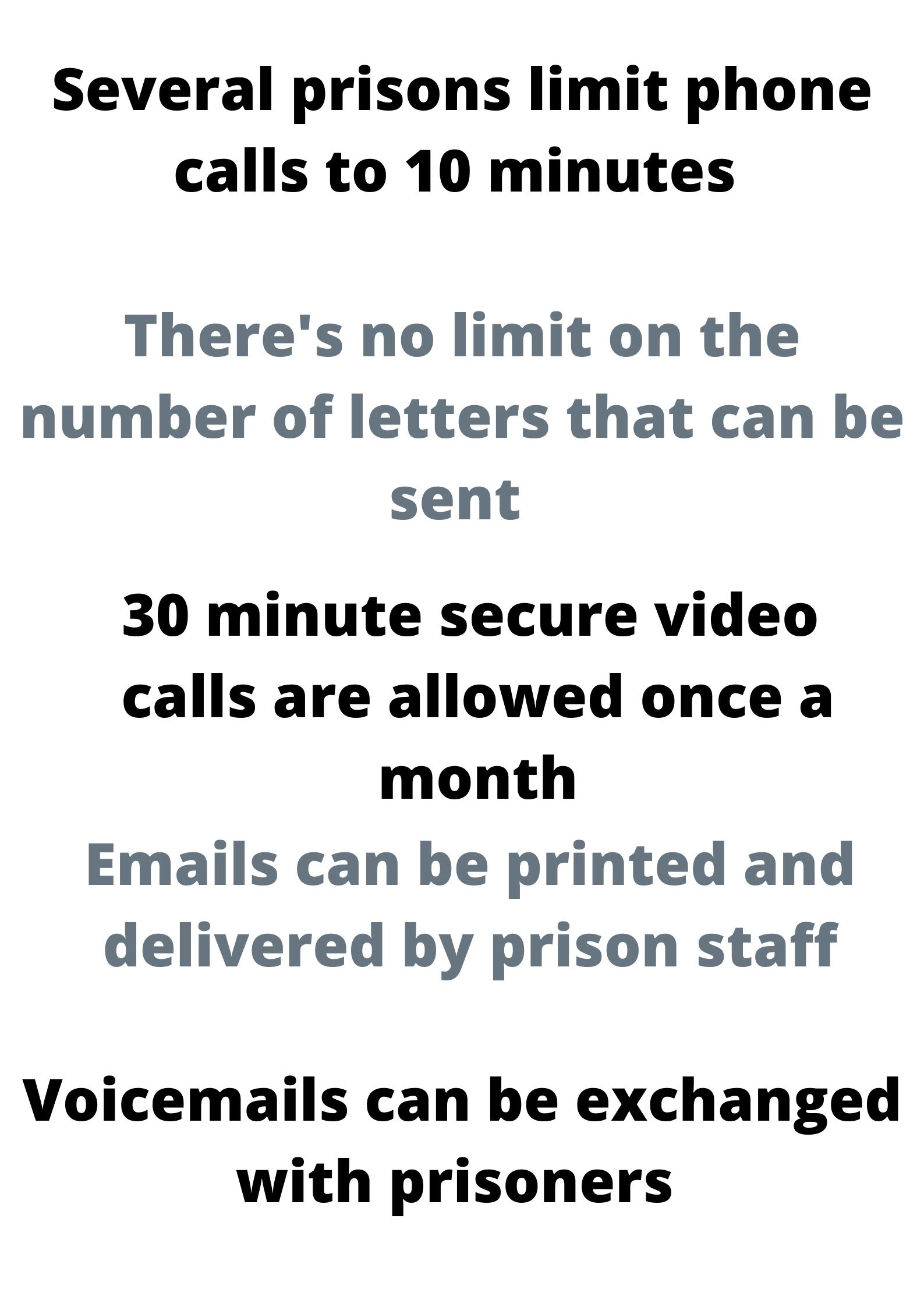

Purple Visits, the video calling system the government began rolling out across prisons during the first national lockdown, did not become available in all prisons until mid-December, nine months after visits were first suspended.

Even now Purple Visits are accessible, they offer little benefit to families with young children, according to Michelle, because the security system is often set to cut the connection when it detects movement in the families’ homes.

For her family, the time-limited calls are frequently interrupted, since her youngest son struggles to stay still.

“My four-year-old doesn’t have any meaningful contact with his dad,” she adds. “The relationship he’s got with his dad at the moment is non-existent.”

On 29 March the MoJ enabled prisons to begin resuming visits on an individual basis, when each prison reaches a low enough threshold on a specific framework.

The group of mothers told me they would prefer a provisional date for resuming visits, like the Prime Minister set out for reopening the country, because under the current plan most families have been left with uncertainty.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice said: “There is no question our response has saved lives and helped protect the NHS, with infections and deaths in prisons significantly lower than predicted at the start of the pandemic."

As of March, there have been 93 deaths of prisoners from coronavirus. Public Health England modelling in March 2020 suggested there could be 2,300 deaths.

The MoJ also said they have worked on improvements to the video calling system, which will be rolled out across prisons.

While these improvements are welcomed by families, many remain desperate to know when visits will resume.

“My newborn is missing out on vital attachment and bonding time. If the visits were on, he’d be able to smell his dad and he’d be able to put a face to the voice he hears on the phone,” Adele says.

Click and zoom to view prisons (green markers = open for visits / red markers = closed for visits)

The new guidelines also limit the number of visitors to one adult and two children or two adults and one child.

Michelle, whose husband’s prison imposed the same conditions when visits resumed last summer, says parents will be left with an impossible choice.

“It was heartbreaking for me because I had to leave one behind,” she explains.

Her oldest son, 17, volunteered to give up his place. “He had to take that choice on his shoulders to not go and see his dad for the benefit of his little brothers, and he shouldn’t have ever had to make that choice.”

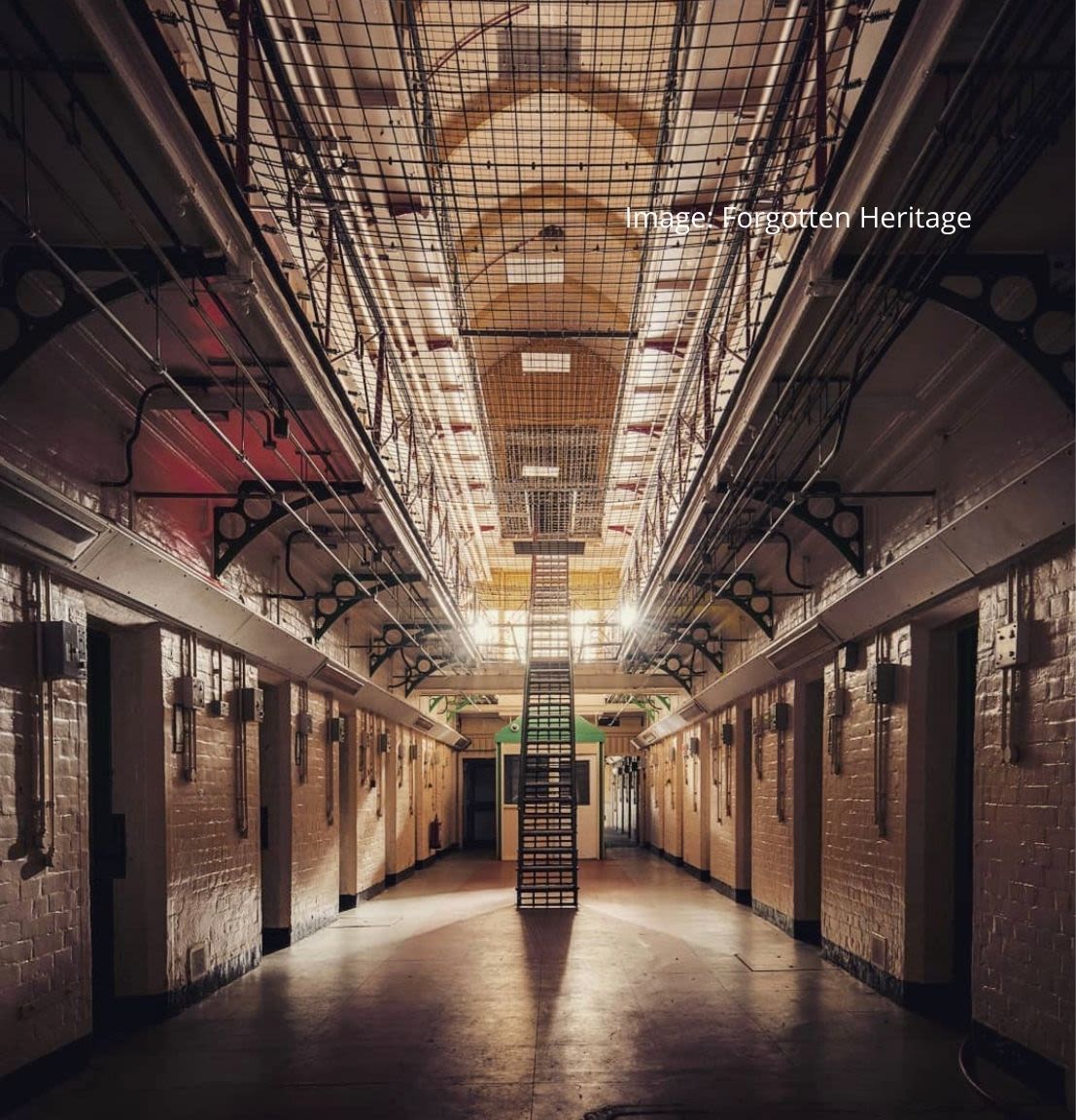

Like with visits at the end of last year, prisons will require visitors to social distance, and many are using screens and booths in visiting halls.

We have been operating visits for just over 2 weeks in closed conditions. To assist us in keeping the establishment COVID safe we have designed booths in the main visits hall. We do not have a date for these being in operation, but we are hoping for the beginning of August. pic.twitter.com/Dx1DTDK6UC

— HMP Humber (@HMP_Humber) July 24, 2020

Adele is unsure if she will allow her toddler to visit regularly because of the distress the measures previously caused him. “He couldn’t understand why he couldn’t get to my partner. He found the door to get you through and obviously it was locked, and he was shouting, ‘let him out, let him out’."

Vix says she won’t take her children while they can’t hug their loved one, labelling the situation inhumane.

Ultimately, the mothers wish more attention would be paid to their children’s distress, which they feel has gone largely ignored.

One mum, in her final words to me, said: “It’s hard for us trying to be a voice for these children when the world just turns a back on them.

“Our children are the forgotten children of the pandemic.”