Making Wimbledon Happen

Behind the scenes of the world famous All England Lawn Tennis Club

Novak Djokovic and Simona Halep took the headlines from Wimbledon 2019, finishing in style as victors in the Championships’, but the true stars of the show could be those behind the scenes. While this year's tournament was a fortnight packed with action and drama, as well as tears, cheers and jeers to the athletes on court, many casual viewers at home will be clueless to the work that goes on at Wimbledon to earn its rightful name as the world’s most famous tennis club.

While spectators were basking in the south-west London sunshine with a punnet of strawberries and cream in one hand and a glass of Pimm’s in the other, Lewis Steele took a look behind the scenes to see how the All England Lawn Tennis Club functions in preparation, during and post-Championship fortnight…

I compare it to what I tell my kids about Christmas. Santa Claus works all year round making the toys and watching whether the kids are behaving, then has his big day just once a year. Here [at Wimbledon], we work all year round to make the tournament special, and it is all worth it for those two weeks in July.”

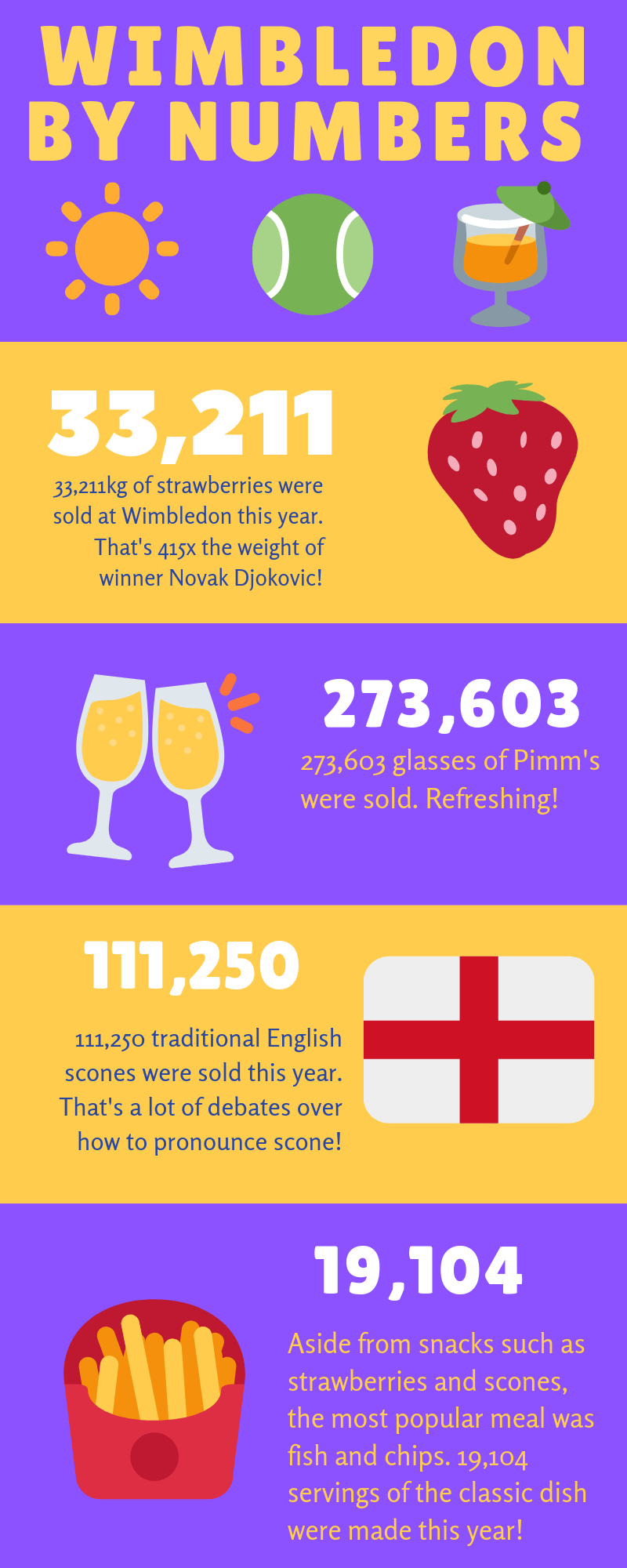

Neil Stubley has worked for the All England Lawn Tennis Club for more than two decades after first joining as a groundsman in 1995. He compares his nerves in preparation for the Championships’ to that of a Grand Slam tennis star, but he wouldn’t have it any other way. As Head of Courts and Horticulture, his primary role is to ensure the hallowed turf around the grass courts is kept in pristine and perfect condition ahead of the tournament in July. While the Championships may only last two weeks, the courts are needed again for members just two days after it finishes, so the work never stops for Stubley and his team.

Speaking to me in the calm before the storm, ten days before the tournament begins, Stubley described the process of preparing for the Championships.

“We work around the clock all year round, and renovation begins not long after the Championships,” Stubley explained.

“From the start of April the grass is taken down a millimetre a week from 13mm to 8mm, ready for when the courts open in mid-May for members.

“The nerves kick in about a month before. I used to let the anxiety bother me, but now I use it to my advantage. If I didn’t worry about things, our standards would drop.”

Days after Novak Djokovic claimed his fourth Wimbledon title in the 2018 final, Stubley and his team were in preparation for this year's Championships. There isn’t a period of rest after the tournament, the team are straight into the hard graft ahead of the next year.

Seeded, fed, covered and now getting a little drink. Less than 48 hours for a complete renovation including steaming. Amazing work from the team #Renovations #TeamWork pic.twitter.com/7NfIVhS26Y

— Wimbledon Groundsman (@AELTCGroundsman) August 23, 2019

The court is stripped (or shaved, which is apparently the correct word in horticulture terminology) and then relaid with seven tons of topsoil and 54 million seeds of perennial rye scientifically manufactured and developed for maximum resistance to drought as well as wear and tear. The grass is then spoon-fed nutrients and encouraged to grow using artificial sodium lights. And while they may use cutting edge technology for some aspects, it is an old-school electric mower that is used to cut the grass, to prevent any possibility of an oil spillage.

In the weeks before the tournament, Stubley uses a soil impact machine known as a Clegg hammer, which tells him the exact hardness of the court, as well as the moisture content every 50mm.

Stubley said: “It sounds a lot doesn’t it? That’s just for one court. There are 40 courts in total, including the practice ones. Just because they are practice courts, it doesn’t mean they require less time or effort than Centre or Number One Court.

“You can’t have a player warm up on a surface completely different to what they will play on.

“It’s stressful and I’m not saying groundsmen in other sports have it easy, but tennis is different in that you have fourteen days of play on the same court. In a football or cricket World Cup, there’s different stadiums and pitches, or in golf the Masters only lasts a weekend, with tennis it’s all go for two weeks.

“My lawn at home is a mess,” Stubley joked. “I go home and the last thing I want to do is cultivate the perfect lawn. It’s like a chef – the last thing they want to do after a long shift on a hot day is make dinner. I’ve got a dog and a couple of kids, so yes my lawn is worn like the baseline on Centre will be after the tournament.”

Since speaking to Stubley before the Championships, the Centre Court pitch has been stipped and treated. Take a look at the sliding image reveal below and see for yourself the work they have done in a six week window... impressive?

[Photos of Centre Court below courtesy of Neil Stubley]

Stubley is crucial to the operation of recovering, preparing and maintaining the courts, but he couldn’t do it without his right-hand man or most infamous staff member at the All England Lawn Tennis Club: Rufus the Harris Hawk.

While the sky is the limit for many young stars at Wimbledon, including Coco Gauff who was the underdog of 2019, Rufus flies higher than most at Wimbledon, with a vital job to do. Pigeons often eat seeds that aid the courts, or fly on during play to distract the players. Rufus’ job is to stop the pigeons.

Only the two World Wars have stopped Wimbledon in the past, so it would be outrageous for a pigeon to stop play - Rufus makes sure that is not the case.

Rufus has patrolled the skies over the grounds for over ten years now, and has a number of clients other than Wimbledon, including Westminster Abbey, Northampton Saints (rugby) and Fulham FC.

His working day starts at around 4.30am, well before play begins, with the simple task of scaring pigeons away. It may sound like a pointless job, but it is vital. Imagine the scene: Roger Federer serving for a match, only to be put off by a flock of pigeons. Rufus is key for the players, and also for the maintenance of the turf.

Imogen Davis, Rufus’ handler, said: “The pigeons know Rufus protects the skies around here. His diet is similar to a player, high in protein! He’s met some of the players, Nadal and Federer have said hello to him.

“He’s been here for over ten years and his main job is to keep the pigeons off court, they often come in and eat the grass seeds. There are a lot of places in the stands of the bigger courts to nest and roost, so Rufus is here to remind them that this is his territory.”

Davis is part of a small family business – Avian Environmental Consultants - that has been at Wimbledon since 1999. He isn’t heavy, but with a wingspan of more than a metre, Rufus can rule over the territory around the stadium, acting as a deterrent for all birds.

In 2012, Rufus was stolen from a car parked on a private drive in Wimbledon, but was handed in to the RSPCA three days later.

We can confirm the news is true RUFUS HAS BEEN FOUND safe and well & reunited with family!! Thank you so much for your support #FindRufus

— Rufus The Hawk (@RufusTheHawk) July 1, 2012

“It’s a lovely job,” adds Davis. “I was born into a family that had hawks so it comes as second nature to me. I always presumed every family had hawks flying around their garden. I love the job though and hope to continue for many years.”

Harris hawks live for around 25 years so Wimbledon will be safe of fouling pigeons for now, but Davis and her team have younger birds which she describes as “apprentices” ready to takeover when Rufus retires.

Rufus keeps the air clear of pigeons, while Neil Stubley keeps the turf in tiptop quality, meaning the players have perfect conditions to flourish.

But Wimbledon doesn’t stop with what happens on court…

[Photo credit: Wimbledon Images]

As well as the immaculate grass, Wimbledon earns praise for the gardens around the courts. While the other Grand Slams – Australia, France and the US – may have advertising hoardings reaping financial gain, Wimbledon is popular for its elegant and divine gardens.

Head gardener Martyn Falconer is in charge of maintaining the gardens and making them look presentable to the fans that come to the Championships.

The garden setting of Wimbledon makes the championship unique. Falconer, who oversaw his 19th tournament this year, said: “For a tournament played on traditional grass, the gardens are what make it special or different to any other.

“People come here to watch the world’s finest tennis players but if you can’t get a ticket on the bigger courts, some just sit around and admire the gardens. My job is to make them presentable.

“I’m proud of the gardens. It’s nice to see people stopping to look at them.”

This year saw the unveiling of two ‘Living Walls’ on the side of No.1 Court, which was renovated for the 2019 Championships. Falconer oversaw the project which involved 15 different plants and took inspiration from physics imagery to reflect the ‘movement’ of a wave pattern to relate momentum with speed, such as a tennis ball being hit.

Working with Chichester-based company Biotechture for 14 months, 245m² of wall were designed to fit with The Championships’ tennis in an English garden feel.

14,344 plants were used in the wall – each was grown in West Sussex at Biotecture’s plant nursery. The plant colours were selected to reflect the Wimbledon brand with purples, mauves, whites and greens.

Initial planning for the Living Wall started in 2014 and Biotecture planted a Wimbledon Trial Wall at their plant nursery in 2017. The on-site installation of the Living Wall framework started in February 2019, with the installation of pre-grown plants in April 2019.

Falconer adds: “The sea of colour is timed to flower at its best during July for the tournament, but the grounds are open year-round for public tours and for members, so it keeps me busy.

“The secret to creating a good garden is realising there is always something to do. We start for the next tournament the moment the previous one ends. We have to look for new ways to keep it interesting. I often visit Chelsea and Hampton Court flower shows to get a feel for what people like and don’t like.”

Falconer is a seasoned gardener with years of experience and has a Masters qualification in horticulture – he wrote a 10,000-word dissertation on the topic: ‘The Perception of Tennis in an English Garden.’

Looking at his gardens, he has gone above and beyond to apply the theory to the hands-on nature of his job at Wimbledon. Falconer said: “I may not be good at tennis but I bet you I’d beat Rafa Nadal at a gardening match!”

It’s not just the gardens that have been overhauled in 2019, with No.1 Court - the second largest court behind Centre Court - getting a large renovation ahead of this year’s Championships.

Originally opened in 1924 to seat 2,500, the No.1 Court was last renovated in 1997, when it was upgraded to fit 11,432 with an array of new facilities. In 2013, the All England Club launched a ‘Wimbledon Master Plan’, setting out the vision for the future of the club, including a major revamp of No.1 Court.

Sir Robert McAlpine was the lead contractor, who commenced a three-year complex build.

No.1 Court now has an increased capacity of 12,345, with a retractable roof and 15 refurbished hospitality suites.

A total of 89,222 design and construction documents were produced during the life of the project; 333 truckloads of earth were removed from site (with 98% of waste being delivered from landfill for re-use); more than 40 miles of scaffolding tubes were connected; it required an average of 80,000 man hours per month to complete.

Sheffield-based company SCX were at the heart of the construction, especially of the roof, which requires 164 drives and 44 motors to move it. 7500m2 of fabric was procured for the roof assembly, enough to cover 38 tennis courts. The fabric cover weighs four tonnes.

The roof takes between 8-10 minutes to fully retract or deploy, and is 75m wide and 90m long when deployed.

Hospitality at Wimbledon

[Photo credit: Wimbledon Images]

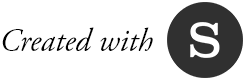

Elsewhere in the grounds, hospitality is key. Marquees go up, food kiosks - serving whatever you can imagine - are erected, and an army of yellow-jacketed workers patrol the grounds to ensure cleanliness. Approximately 2,500 staff members deliver over 140 food and drink outlets that will cater for all needs (and budgets, given the fine dining in the Royal Box prices!)

Anthony Davies is Head of Food and Drink at the All England Club. He joined in 2014 in a role to devise a strategy that matched the organisation to ensure that visitors get the best of their experience at Wimbledon. Having previously worked for elite level hotels and restaurants, Davies knows how to make a big event function well.

He said: “The camaraderie is great, and there’s not much better than seeing all customers smiling and happy with the event.

“We like to think of the Championships as tennis in an English garden, so we want a picnic feel to it. Back in Victorian times there was just a two week period for strawberry season, it just so happened to coincide with the two week period when Wimbledon was.

“Not everyone who walks through the gates is lucky enough to go on the bigger courts, but it’s still a bucket list sort of day to sit on Henman Hill and take in the atmosphere. That’s why we have to make it extra special, and I think we do!”

While most of the outlets are grab-and-go style eateries, there are also many fine dining options, and don’t forget the chefs don’t just cater for the 39,000 spectators who flood in per day, they have to fulfil the dietary requirements of the athletes.

For the players, there is no set menu, the chefs make whatever the player desires. If a player wants pasta with honey, that is what they get. That is the strangest request Executive Chef Gary Parsons has dealt with, but he won’t reveal which player ordered it.

He said: “It’s not like working in a pub where you have an order come down and you know it’ll be a few burgers, fish and chips or whatever, these are athletes at the end of the day and each players diet is different.

“Pasta pre-match for their carbs and energy, potentially stir fry after, maybe sushi. In the first week, we serve nearly one thousand meals to players.”

What’s for pudding, you may ask. The answer, according to Parsons, is strawberries. The symbol of Wimbledon that is near the top of many bucket lists worldwide: ‘have strawberries and cream at Wimbledon’. Whether it’s with cream, just sugar or with melted chocolate, strawberries are a staple of the Wimbledon diet for spectators, players and staff.

The strawberries come from a farm in Kent, picked at 4am each morning. They are then swept to SW19 in refrigerated vans where 50 caterers take them. The price of the strawberries - £2.50 - has remained the same since 2010.

Marion Regan, who owns Hugh Lowe Farms in Kent with her husband Jon, loves being the heart and soul of the hospitality side of Wimbledon.

She said: “Within a day of the strawberries being picked, they will have been taken to Wimbledon in a truck and hopefully enjoyed by the people.

“It’s a long day for our strawberry pickers but they all enjoy it. We have a lot of workers come over from Eastern European countries. They are so hardworking.”

Obviously the question of Brexit is one Regan has tackled before. She said: “I hope when we do finally leave there will still be a way to allow these people to come over and do their seasonal labour.”

🏆 Best #Wimbledon mixed double? Our pick is still strawberries & cream. 🍓 #EatTheExperience pic.twitter.com/mjdBQ1Telh

— StubHub (@StubHub) July 10, 2019

This years Championships saw the introduction of a vegan version of the strawberries and cream.

Dawn Carr, director of vegan corporate projects at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals Foundation (PETA), had a key role in persuading Wimbledon to make the change.

She said: “PETA first urged Wimbledon to offer strawberries and vegan cream in 2017, and we’re delighted to make a racquet about the new cruelty-free treat.”

Another staple of Wimbledon is Pimm’s, which sets punters back an expensive £8.50. Pints of beer, in comparison, were £5.80 on average.

One spectator, Jamie Gordon, from Stoke, said: “Pimm’s is expensive but I’m happy to pay a little more to get in the Wimbledon spirit.”

Another in attendance, Olivia Woolnough, from Nottingham, said: “I’ve been Wimbledon a few times and the food and drink are one of the best bits. I’ve been lucky enough to see some good tennis but all the options make it possible to have a great day out where the tennis is an added bonus!”

Now it is time to test your knowledge and see how much you have learnt so far about the weird and wonderful world of Wimbledon...

Five curios of Wimbledon

A list of the strangest unknown tales of SW19

We’ve learned about the maintenance of the grounds and how the All England Lawn Tennis Club looks in pristine condition all year round, but there is plenty more still to learn about the Championships.

Did you know for example, there is a hairdressing salon, travel agency and theatre booking office inside the grounds? Or what about a select group of 210 men and women who greet the spectators, manage queues (that can boast up to 10,000 people queuing) and provide a feel-good factor to the guests?

All of that and more here, as we have a look inside and pick the five greatest curiosities of the greatest tennis show on earth.

Wimbledon has a maze of underground tunnels

While spectators are out in the summer sunshine watching tennis, eating strawberries and drinking Pimm’s, workers - over 1,800 of them - pass through underground tunnels that connect every corner of the site. In operation since 1997, these tunnels provide the veins of Wimbledon, circulating the lifeblood of the championships - the workers. This means they don’t have to fight through the crowds of excited people to get from A to B, allowing an easy route around the site.

There are two main tunnels. The royal route runs from Centre Court to No. 1 Court, alongside a buggy drive. There are many underground subterranean rooms that are connected by these tunnels, from drug-testing rooms to standard dressing areas.

It isn’t just staff that use the tunnels, with players using them also. Busy at the best of times, the tunnels ensure the utmost safety, players have been known to suffer a bump or two - Rafael Nadal suffered a comical bang to the head when jumping on the spot ahead of a match in 2017.

‘The List’ of proposed improvements

Wimbledon always looks for ways to improve. While major decisions such as the renovation of No.1 Court ahead of 2019’s Championships will get mass media attention, little decisions follow a similar democratic process. The All England Club maintains what it calls ‘The List’ - an exhaustive and comprehensive tally of everything staff members suggest they can do better.

With over 1,000 things added to the list in a process that starts immediately after the tournament has finished, you may think some of the items get hastily ignored. This is not the case, as every item on the list gets discussed and addressed before the next Championships.

Mitzi Ingram-Evans, Championships Operation Manager at Wimbledon, has a key role in the functioning of the Championships.

She said: “The List is a bit of fun sometimes but also it can have huge impacts on Wimbledon. The renovation of the No1 Court this year was suggested because of it, but they can be as small as changing the font on a signage post.

“We like it because every proposal gets equal weight when we read through them all. It doesn’t matter if you’ve worked here for 50 years or it is your first Championships. It means we can get better year on year in a democratic way.”

There’s a special room under Centre Court to store over 50,000 balls

Around two lorry-loads (over 50k) of balls arrive in total from Slazenger, who have supplied Wimbledon since 1902. They are then stored in two rooms beneath Centre Court at a constant temperature of 20C. Before play each day, 20 tins of balls are delivered to each court. Six new balls are introduced every nine games, after the first seven games, and the stock is replenished each match.

In a control room, the ball handlers monitor the matches from a computer screen, watching out for matches that might require extra balls. During John Isner and Nicolas Mahut’s 11-hour, 183-game thriller in 2010, over 40 cans of balls were used. Luckily that won’t happen again, with the tie-break rule now kicking in at 12-12 in the final set - a rule new for this year.

Used balls are sold on to fans and if they aren’t up to standard, they may be given to other organisations. People do steal balls to take home as memorabilia, with Wimbledon turning a blind eye to this, so if you’re lucky enough to catch a ball, don’t be shy.

There’s a hut of stringers on site

Working around the clock in days that often start at 6am and finish after 11pm, the stringers have one of the most important jobs on site. Think of this role as the equivalent as the team that check the tyres at Formula 1 races, the tension of racquets can be the deciding factor between a win or a loss.

Jeremy Holt pulls the strings from a hut by the Aorangi Pavilion as Head Stringer, in what will be his team's eleventh year at the championships. The number of racquets they have worked on has risen year on year - last year they tightened around 4500 racquets, nearly double that of 2009. In total, they use around 30 miles of string during the two weeks.

Preferred tensions vary from player to player - some like a tight racquet of 65lbs of tension, whereas Daniel Nestor - a retired doubles player - asked for a staggeringly loose tension of 14lbs.

Jeremy Holt explained: “The lower the tension, the more power the player has, whereas a higher tension allows more control.

“Few players have broken strings, it’s just they like freshly strung racquets for every match. It’s not like cricket where a worn bat can get good results, tennis racquets need to be perfect. So we’re always busy.

“It’s a fun job. You could be stringing away and look up, and there’s Roger Federer. It’s a bit of a pinch yourself moment every time, but we love it.

First on Centre Court

For 50 weeks a year it remains out of bounds for players, and experiences only the tender care of the ground-staff team. But with the grass perfected over the course of four seasons as we have seen, the first players to experience a match on it this year were not defending men’s champion Novak Djokovic and his opponent Philip Kohlschreiber - which was the first match - but a select group of AELTC members.

Every year, on the Saturday before the tournament, a group of female players (lighter than their male counterparts and less likely to inadvertently cause any damage to the court) step out to test that the grass is pinpoint perfect before the players take centre stage on the first Monday.

Traditions and regimented officiating

Speaking of the strawberries and cream and how it has been a staple since Victorian times, Wimbledon is haven to some of the longest standing traditions in not just tennis, but sport in general.

Since the first ever Wimbledon Championships in 1877, every player has been required to wear all white uniform - off-white, cream, or even a tint of another colour is forbidden. Wimbledon is also the only tennis event that is watched live by the British royal family; Centre Court has a Royal Box reserved exclusively for members of the royal family and their guests, seating 74 people in total.

Aside from the dress codes and a hint of royalty, Wimbledon follows strict traditions and while it may be well over a century old, the Championships follow a regimented process when it comes to officiating, be it in the form of umpires or ball boys/girls.

Ball boys or girls, or BBGs as they are known, go through a gruelling process to ensure they have the right attitude, fitness and mental stability for the job.

In a column for the Independent, Tom Peck, now a cartoonist for the same paper, wrote: “Stood in even rows, six wide, six deep, numbers fixed to our front, we look like those Filipino prisoners on Youtube about to do the Thriller dance. But the life of a South-east Asian inmate, I will soon find out, is easy by comparison.”

Talking now, Peck recalls his experience at training camp to be a ballboy. “I remember, I wasn’t Tom, I was simply ‘number 213’. You refer to everyone as Sir or Miss. We were put through our paces - star jumps, press ups, high knees, heel flicks, you know the drill, but to the point that you’d have no more energy to give.”

Roughly 1,000 children - between the age of 14 and 18 - apply to be a BBG, from schools around south-west London. 250 are selected to make the finals, and the best of those will advance to officiate in the bigger matches such as finals and semi-finals.

From February through to July, the chosen ones go through 2.5 hours of training per week, learning step by step how to become an efficient ball boy or girl.

Sarah Goldson, a PE teacher by nature, heads up the classes. She compares the process to the X Factor.

She said: “It is gruelling for sure, we have to put them through their paces a little. The ability to listen to instructions is what we’re looking for.

“The hardest thing we teach is for them to stand stock still, which means to literally not move a muscle - trust me it’s harder than it sounds. We can’t have a player going to serve to be put off by a fidgeting ball boy or girl.”

Four teams of six work the top two courts, with one hour on and one hour off. The BBGs also learn how to throw a ball efficiently, how to hand dropped racquets, drinks and towels to players.

While they are encouraged not to speak to players, some of the stars enjoy chatting away while playing - Nick Kyrgios for example is always one that loves to spark a conversation.

Nick Kyrgios needed a hug, so he found a Wimbledon ballboy http://t.co/GMchm1szlR pic.twitter.com/mdeWSddKJV

— For The Win (@ForTheWin) July 6, 2015

Dustin Brown is known to ask for the same ball back if he has won a point with it, which can add to the workload for the BBGs, while Rafael Nadal presents a variety of unique challenges - he is often known to hand rubbish (such as a wrapper from an energy bar) to a ball boy or girl to place in the bin rather than doing it himself.

An unnamed ball boy who took part in his second Championships this year, said: “It’s so fun, hard but good fun. We have a system where we’re on for an hour then off for an hour, so it keeps us fresh. I’m just applying for college and having this on my CV was the first thing they asked about in the interview.

“The training process is brutal. I remember jogging to a ball and getting loudly shouted at for not sprinting. It’s like that SAS programme on the tele!”

While the process is a tough one, officiating at the Championships is an honour for all involved and a good example of how Wimbledon link up with the local community by selecting children from nearby schools.

Locality is the case for the BBGs, but overall, Wimbledon is a global event. Many of the workers that pick the strawberries are from Eastern European nations; this year's winners - Novak Djokovic and Simona Halep - are from foreign nations; many of the materials used at the All England Club are from all around the country.

All these weird and wonderful facets combine to create a festival atmosphere at SW19 for two weeks in July, but as Neil Stubley said, Wimbledon is far more than just Championship fortnight.

Overall, Wimbledon is far more than a game of tennis. It is a cultural event that is symbolic to British society, with the camaraderie, strawberries and cream, and general feel good atmosphere at the All England Club. There is never a boring day at Wimbledon and it is clearly not just a 14-day-per-year job, it is a year round passion for many, including some of those we have heard from here. So whether it is the hut of stringers, the process of getting a court up to standard, or how Rufus the hawk is a key member of the groundstaff, hopefully you have learned some knowledge you can use next time you're in a conversation about Wimbledon.

Game. Set. Match.