“Hi, I’m Kami. I’m courageous, confident, bubbly, kind and friendly.

“Some of my interests are fashion, beauty, food, dance, art, music, fitness, gaming, social media and all things digital. I love being creative,” she says.

Kami is an Instagram influencer. But she isn’t human.

She is a computer-generated image (CGI).

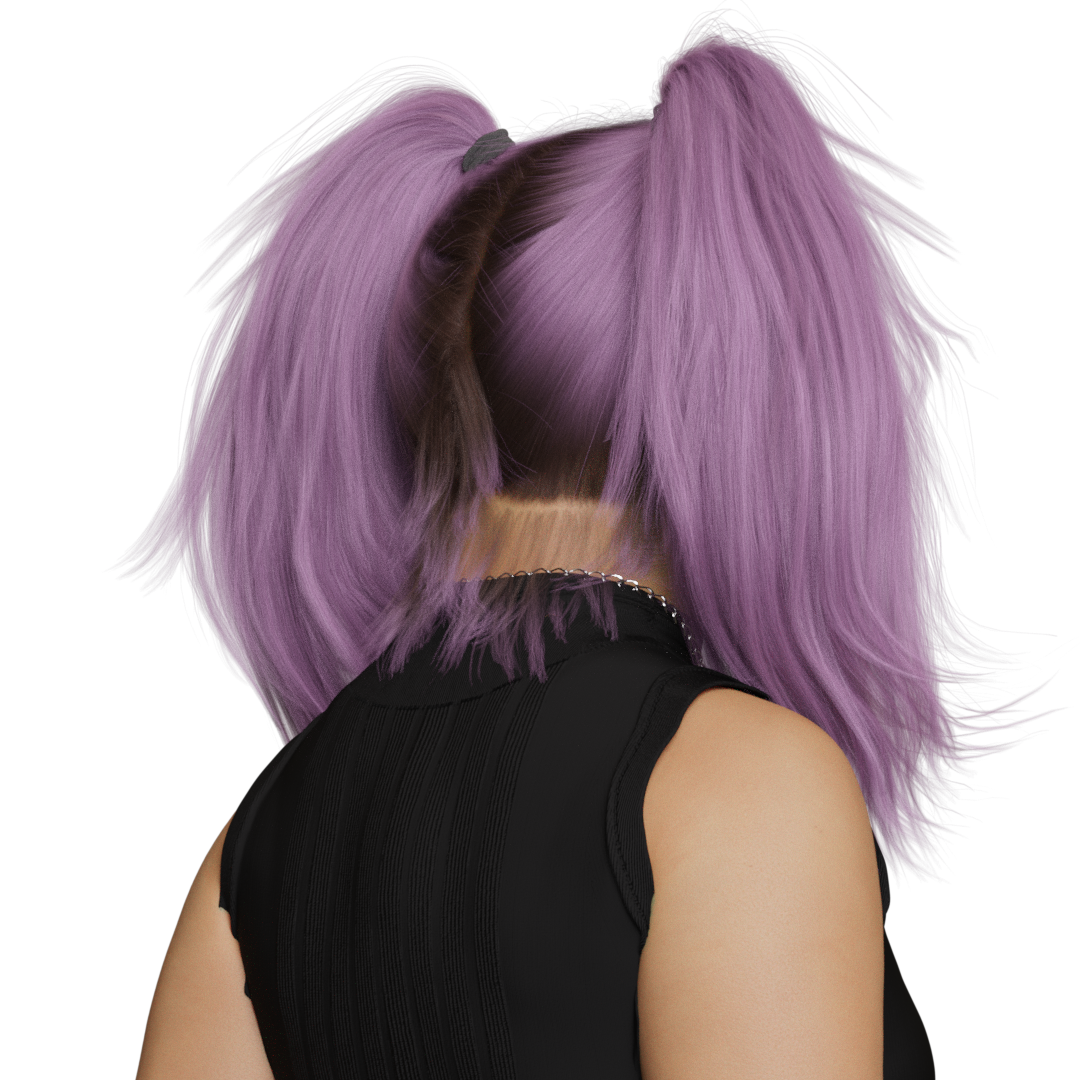

Hover over the image below to reveal Kami.

First image: One of the people with down-syndrome who inspired Kami's appearance. Second image: Kami

The purple-haired character is the first Down syndrome virtual influencer and represents the emerging new wave of diverse CGI influencers.

Unlike most CGI influencers, Kami is not AI.

So, what exactly is a CGI influencer, and how do they work?

Social media influencers - famous for their online content - are often accused of misrepresenting real people.

But, ‘people’ like Kami are blurring the line between what is real and fake.

At first glance, it might be hard to differentiate a CGI influencer and any other influencer - whether someone is 'bot or not' if you will.

CGI influencers post their picture-perfect lives, sport the latest fashion trends, and even hang out and collaborate with celebrities.

You may remember the controversy surrounding Bella Hadid and Lil Miquela kissing in collaboration with Calvin Klein.

Most of them regularly post on Instagram about their daily life, all while looking flawless. Artificial intelligence never looked so beautiful.

Their lives look too good to be true - because they are.

CGI influencers are usually designed and given a personality through artificial intelligence (AI).

This just means that their creators input her personality on a computer. And, with the more entries made, the better they get.

Their developers use this AI to create social media posts and sometimes interact with followers. For example, one virtual influencer, Serah Reikka, has an online chatbox.

Programmers even use software such as Google Trends to see what people are searching for at any given time and can tailor their posts to reflect these results. All of these are unattainable for the average human influencer.

This artificiality seems to have made them more famous. Some are even getting more followers than human celebrities and influencers.

Take UK influencer Saffron Barker, for example. Barker rose to fame through YouTube and has appeared on Strictly Come Dancing. But, she has fewer followers than Lil Miquela, the most followed CGI influencer.

These life-like avatars are new to social media, and many users seem fascinated by them. How are they created? How did they get all these brand deals? Who controls them?

Questions like these are some of the reasons why Gen-Z and millennials appear to be following them.

The creators of these realistic digital influencers understand these burning questions. Developers have learned that they can't just survive off of pretty photos and need to have compelling personalities and backstories.

Lil Miquela’s creators have done precisely this. For Black Mirror fans out there, she’s basically a real-life Ashley O. They use comedy in her posts and show her specific interests, such as going to bars and malls.

Some programmers have gone one step further to make them more unique. For example, Serah Reikka is half-cat, half-human, which may have also been a tactical move. After all, cat content is always going viral on the internet, and 'Cat' is searched 1,219,483 times per hour.

Digital influencers, who are as effective at influencer marketing as their human counterparts, are also more diverse.

1. Lil Miquela

Lil Miquela is 19 years old and is half-Spanish, half-Brazillian. She describes herself as a "Robot living in LA" in her Instagram bio.

2. Shudu

Shudu is a black digital supermodel. She has collaborated with Balmain and Vogue Australia. She was created by The Diigitals, the world's first CGI modelling agency.

3. Bermuda

Bermuda has the same creators as Miquela. She's a singer/songwriter, and it's unknown whether her voice is computer generated or if it's a real person.

4. Blawko

Blawko’s Instagram has recently grown by nearly 100k. He is also friends with Miquela. He's a black CGI model and describes himself as a “young robot sex symbol” whose mouth is constantly covered with designer pollution masks.

5. Imma

Imma is a Japanese digital influencer made by ModelingCafeINC. She has partnered with brands such as Porsche, SK-II Skincare, Burberry, and Valentino.

By contrast, the top human influencers are Addison Rae, Khaby Lame, Pewdiepie, James Charles and Luis Arturo Villar Sudek. Khaby is the only black person.

CGI influencers also tend to post more about diversity, as well as their political views.

“A change-seeking robot,” “Black Lives Matter,” and “Digital character, activist, vegan” are just some virtual influencers' bios. These opinionated, fashionable characters curate our news-feed powered by human likes and shares.

They seem to be profiting off of any political upheaval going on. But, hey, it could be a good thing to get young Instagram users interested in politics, even if it is through the voice of a computerised image.

Their captions are relatable to users and link to the real world through current trends. For instance, Lil Miquela uses famous TikTok songs’ lyrics as her captions, such as ‘Material Gworl.’ She also shows her down days such as captioning a post: "You ever need to lie on the floor to figure shit out? #worstmonthever."

Take your mind back to 2007. Britney Spears is playing on the radio, your Tumblr page is popping, and things like Instagram influencers didn’t really exist.

Did Hatsune Miku ever pop up on your late-night internet scrolls?

For those that missed this former internet craze, Hatsune Miku was one of the first digital characters. A bit like Gorrilaz, as Dr Chico mentions in the explainer video.

She’s a Japanese pop star who goes on a yearly world tour.

Initially, she was a software voicebank, known as a Vocaloid, developed by Crypton Future Media. The company exports sound generator software, sampling CDs and DVDs, and sound effects.

Users could type any lyrics into a chatbox and get Hatsune Miksu to sing them. But, they made a crucial difference in the industry. Instead of just a voice, they added an animated character to go along with it.

The character, made to look like a 16-year-old girl with long turquoise hair and anime-like features, became more popular over time. She now has over 2 million followers on Facebook.

In 2013, Louis Vuitton’s iconic fashion designer, Marc Jacobs, even designed her tour costumes.

Brands began to recognise the potential for digital characters in the fashion world. As influencers are ruling the online space, some think it was only natural that CGI characters followed suit to go with the trend.

Besides advancing technology and people wanting to be creative, they could be a cheap marketing tool.

One professor of computer science, Peter Bentley, says CGI influencers can be “completely controlled, and brands can use them to advertise anything without limits. They may also be cheaper."

From a marketing perspective, they can encourage more sales, according to one study:

So, they might not be real, but their influence seems to be.

They have the added advantage of posing with products anywhere their client wants. They can go anywhere in the world without actually having to travel there.

Not only this, they can be adjusted to fit any brand’s image. Programmers can add makeup, colour themes and outfits with a click of a button, all for little cost.

Generally, brands don’t have to worry about the CGI influencer’s politics. They can easily select those who are not political. Those who do not voice their views are unlikely to be ‘cancelled’. And if they do, they potentially have the excuse of AI malfunctions to blame. In contrast, human influencers don’t have this to fall back on.

This happened recently with an AI rapper, FN Meka. He’s given the appearance of a black male cyborg, and was recently been signed by Capitol Music Group (CMG).

He has over 500,000 monthly Spotify subscribers and more than one billion views on TikTok. His two non-black creators, Anthony Martini and Brandon Le, have received a lot of backlash in the last week. The robot rapper was signed with a record label, even though one of his songs includes the N-word.

His creators have not yet commented on the situation or provided an apology.

His words are created by using thousands of data points compiled from video games and social media.

CMG has now dropped him, but before this black activist group Industry Blackout sent them an open letter saying FN Meka was "offensive" and "a direct insult to the Black community and our culture".

They said it was "an amalgamation of gross stereotypes, appropriative mannerisms that derive from Black artists, complete with slurs infused in lyrics".

The song featuring the N-word was a collaboration with human rapper, Gunna. But, "is currently incarcerated for rapping the same type of lyrics this robot mimics. The difference is, your artificial rapper will not be subject to federal charges for such," they said.

The group added: "This digital effigy is a careless abomination and disrespectful to real people who face real consequences in real life."

For example, in 2018, rapper Kendrick Lamar invited a white man on stage to sing along to one of his songs but interrupted him when he sang the N-word lyric.

Also, country star Morgan Wallen, faced a lot of criticism after being caught on video using the racial slur. He describes in an interview that the extent of the backlash led to “very dark times.”

Language and political views seem to be important factors for human social media stars too. One study found that over half of marketers across the UK, US and Germany would be anxious about working with an influencer who was vocal about social and political causes.

One study found that 59 per cent of black influencers interviewed reported that posting about race negatively impacted them financially. Only 14 per cent of white influencers said they felt this impact.

In May this year, MPs even recommended that the government look into pay standards for influencers as part of a wider investigation. But, there have been no updates since.

Despite that survey’s results, one CGI character's political involvement is paying off.

Ivaany represents her creator’s political views and has received many positive comments.

Her very existence was political - to up the numbers of black influencers.

There aren’t any hard facts or studies quantifying the number of black or minority influencers. Currently, the conversation is just taking place via social media by influencers of colour.

Ivaany is France’s first black ‘digital model’ created by Maison Amany, a French digital agency.

She explains: ”I don’t want people to see me just as a virtual influencer but more as an artist and a 3D fashion model with a vision and a message.

“I am a visual project representing my creator, and I fight for her and her visions.

“We want to put more light on black characters, especially in the 3D and game industry ‘cause we feel like we are not very present there, but also on black women in the digital and technology industry.”

The model feels like she is responsible for discussing diversity issues in real and CGI modelling worlds, saying: “I am the first model created by Maison Amany, an agency created by two black women who are very engaged with our community.

“I feel like I have to discuss and share posts about our community, our culture and everything around.”

When asked whether diversity in the CGI modelling world is positive or negative, she says: “It’s a very good thing as long as it’s for the right reasons.

“I am a black virtual influencer created by a black woman to be a representation for young girls, young black girls, women in tech and digital industry.”

But, not all black CGI influencers have black creators.

One example is Shudu, who has 237k followers, making her one of the most followed CGI influencers.

The fictitious fashionista went viral after attracting interest from fashion brands, celebrities and people who initially mistook her for a real person.

In fact, 42 per cent of Gen-Z and millennials have followed an influencer and didn’t know it was a CGI.

Within two years of her creation, she featured in Vogue and graced the 2019 BAFTA film awards red carpet.

Shudu was created in 2017 by Cameron-James Wilson, the white CEO of The Diigitals, the world’s first CGI modelling agency.

The Princess of South Africa Barbie doll was supposedly his inspiration when creating her.

Wilson reckoned this type of beauty isn’t seen much in the fashion industry and wanted to change that. *

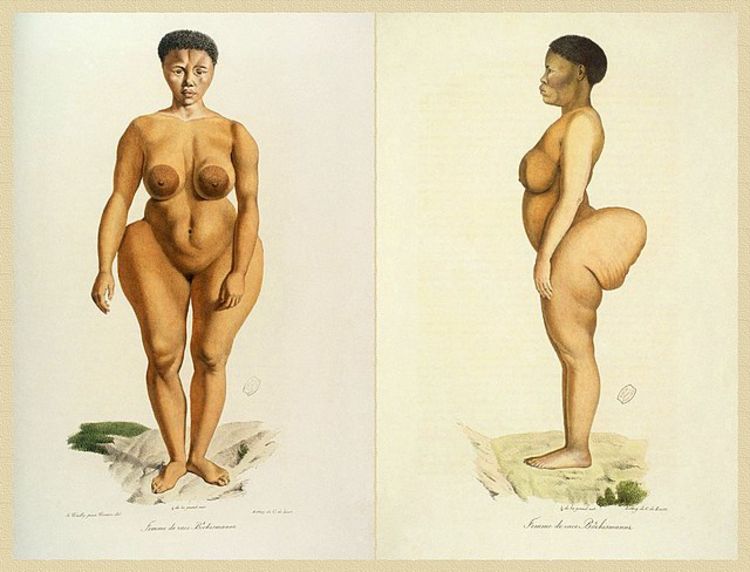

But, this idea of beauty has been seen through the lens of a white guy before. In the 19th century, Sarah Baartman, a Southern African woman, was marched around freak show attractions, all because she had a large bottom and breasts.

Shudu is getting a similar reaction online, such as users commenting: “She is gorgeous... black women are really it” with tonnes of love heart eyes emojis.

But, it seems unlikely that Shudu's management will change.

Like Ivaany, The Diigitals could employ a team of black women to control the CGI.

Dr Chico Camargo, lecturer in Computer Science at the University of Exeter, says: “There’s something that lived experience provides you even if your team all have PhD's for example. I think having more perspectives around you means trying to identify, beforehand, the problems that could crop up by you making what is accidentally a caricature.”

He adds: “You have to remember that there was probably a team thinking, what if we made that character black?

“I'm sure that there are situations where that's totally fine. But there are so many ways that can go wrong.

“Some creations can be noble, like black creators wanting black women to look at my black influencer and feel empowered at the same time.

“I think it all really boils down to money. Is it just some company or somebody profiting from people feeling represented? This is equivalent to Sainsbury's just saying June is pride month and making pride jaffa cakes. Still jaffa cakes. It's still Sainsbury's. Or whether the money is going to black people themselves?”

In an interview with The New Yorker, Cameron addressed the controversies: "I honestly think that those who have really taken the time to speak to me about my motivations understand that it wasn’t this big scheme to profit off of someone".

Even so, people are picking up on the fact she’s created by a white man.

Dr Chico Camargo says: “Audiences care about legitimacy. So when audiences learn that it's actually a bunch of white guys, they can feel betrayed because they're buying into an image.”

In Shudu’s five years of existence, The Diigitals have had many negative comments from news organisations and people on social media.

This is continuing - in Shudu’s most recent Instagram posts, there are comments such as “Honestly disgusting, It’s a white person who created her” and “Wait … A White man created a Black virtual model, and y’all are praising this shyt! Get me off this fckn planet!”

Cameron clarified his creation to Harper's Bazzar, saying: "As a photographer, I work with lots of different people all the time, real people that have inspired her. At the end of the day, it's a way for me to express my creativity—it’s not trying to replace anyone. It's only trying to add to the kind of movement that's out there."

He added: "It's meant to be beautiful art which empowers people. It’s not trying to take away an opportunity from anyone or replace anyone. She’s trying to complement those people."

*The Diigitals and Cameron were contacted, but did not respond.

Text over media

The term originated in a Twitter thread around two years ago when journalist Wanna Thompson noticed white celebrities and influencers imitating black women on social media. They can achieve this through tanning their skin and wearing clothing and beauty styles that originate in the black community.

Long nails, do-rags, hoop earrings and lettuce hems originated in the black community, all of which have crept into mainstream fashion.

This has made its way onto social media, especially on Instagram, by human influencers - i.e. digital blackfishing.

One example is white social media star Emma Hallberg wearing a Louis Vuitton do-rag and gold “Babe” nameplate necklace.

Influencers, such as Emma, are making a profit off of posts like these.

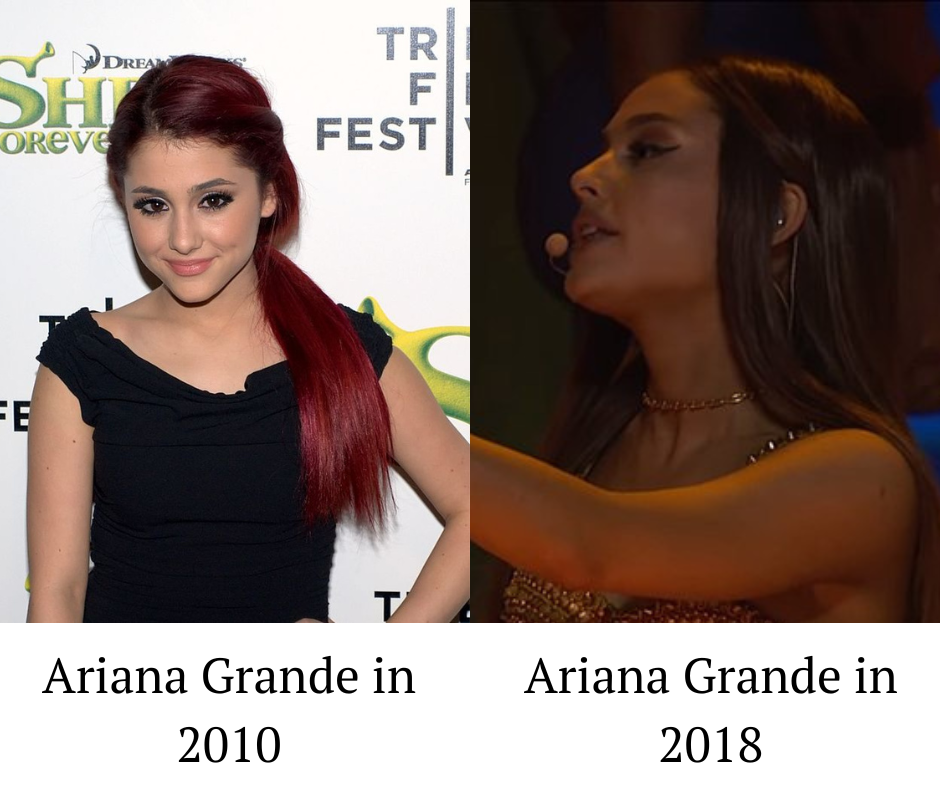

Similarly, some of the wealthiest white celebrities, like Ariana Grande and Kim Kardashian, have been under fire for blackfishing.

Ariana Grande’s skin has been getting darker and darker.

And many of her fans are shocked when they discover she’s white. A lot of people think she’s mixed race:

In reality, she is Italian-American.

Kim Kardashian also has a long history of blackfishing accusations. Most recently, people turned to Reddit to discuss her extreme tan. Also, a viral thread created three years ago called ‘Nigerian Kim’ identifies all the moments she has blackfished.

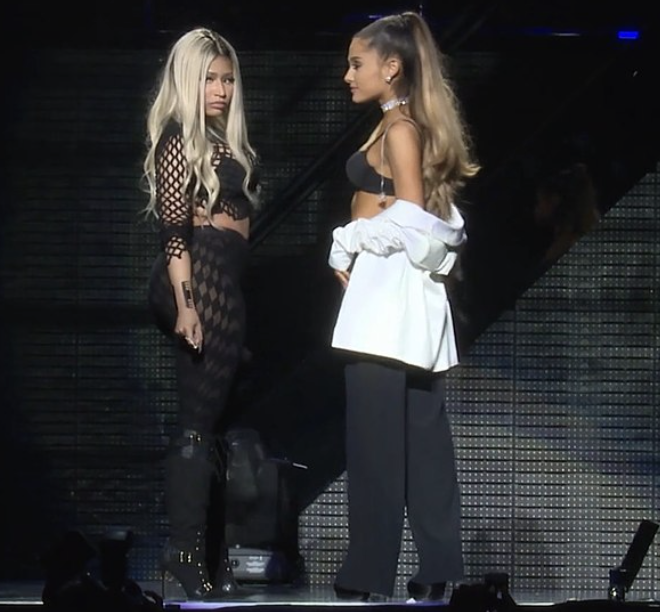

After many layers of fake tan, Ariana reaches the point where her fake tan is darker than Nicki Minaj’s skin - who is black.

At the MTV awards in 2016, the pair sang Side To Side. Ariana is a shade darker than Nicki Minaj.

She’s adopted a “blaccent” to go with her new skin colour too. In interviews, she has used elements of AAVE (African American Vernacular English).

Back in 2020, she featured in a Black Lives Matter and Black History Month playlist. Spotify also put her on the cover of the official Black History playlist. She didn't address any of the backlash.

But, on the cover of Vogue magazine, she had freckles, pale skin and blonde hair. Some say it's as if she is picking and choosing her features depending on the audience.

This blackfishing, by celebrities and influencers alike, is made worse when considering the pay gap between races.

According to one study, the pay gap is 35 per cent, and nearly half (49 per cent) of the black influencers they interviewed said their race led to brand offers below market value.

So, based on this, black women, who may wear clothes from their culture, could be making less than white people appropriating these qualities.

This is similar to how the CEO of The Digiitals is making money from appropriating black culture and digital blackfishing.

However, real-life versions of Shudu are appearing increasingly in the modelling industry.

There has been some progress in the wider fashion world, especially for race. For other aspects of diversity, there has also been an improvement, but they are still a minority.

Across Fashion Month in New York, London, Paris and Milan, 48.6 per cent of the models were of colour this year.

So, there has been a drastic improvement in the diversity of races in the modelling world.

A record 2.2% of models at all fashion weeks in Fall 2022 were plus size, which amounts to 103 people.

In Spring 2022, it was just 1.81% with 91 people.

Fall 2022 also saw a jump in gender representation.

There were 59 transgender and non-binary model appearances.

There weren't any disabled models. Fashion and beauty campaigns feature roughly 0.02 per cent of people with disabilities, although 21 per cent of the population in the UK is disabled.

As well as Shudu, another CGI model with a male creator is Serah Reikka.

Serah is white, slim, and has extremely large breasts.

The purple-haired AI loves video games, travel and cosplay.

She rose to fame by starring in a sci-fi short, Beyond Polaris, featuring a cameo from Elon Musk.

Since then, she has modelled for Russian Fashion Week with Mercedes-Benz and, in 2020, Forbes Magazine’s listed her as one of the top 12 virtual influencers.

Before 2020, Serah was not an AI, meaning a team was behind her to make the content.

Her creator, Jawad El Houssine, started to design Serah for the first time in 2005 when he was a teenager.

Since 2020, Serah is a semi-autonomous artificial intelligence. It means she can choose between a range of possibilities in her database.

He explains why she looks the way she does: “Sereh looks the way the internet wants her to look. She looks like what the internet perceives as beautiful and meets the internet’s beauty standards.”

He says regarding diversity, “Keep in mind that in 2005, the world was completely different. And no one asked us this kind of question with diversity. It was not something very important.”

Serah spoke about what it’s like to be a virtual influencer and aspects of diversity:

Jade McSorley, who came third on Britain’s Next Top Model, is now studying a PhD in fashion tech and sustainability at University for the Creative Arts.

She raised concerns about brands purposefully making their CGI models diverse.

The ex-model used the example of Brenn, who is a CGI influencer with stretch marks.

She says: “I think it’s quite a tokenism. I think it's a bit meta-washy.

“Models have been criticised for years for being too thin. So when something's suddenly created and thought about how they will make an imperfect avatar, what is imperfect to them?

“Everything is chosen for a reason, which then brings issues because everything is subjective to the person creating it.

“That's why I honestly believe that a digital version of yourself is ethically more sound than creating a virtual CGI influencer.”

She adds: “The most imperfect person is a human, not a CGI model. But, when I’ve spoken to models for my research, some models have not got jobs because they've [the brand] basically decided, oh, we can't find the model we want. So we're going to create a CGI model. So they've missed out on a job that could have paid for their livelihoods. And they've been replaced by CGI models because they couldn't find the person that fit all the points they wanted.”

“I think if you're going to create CGI influencer, then I would think what is true to your brand, rather than trying to check boxes.”

Another huge ethical implication is toxic beauty standards, something social media platforms seem reluctant to stop. As revealed in leaked documents, Facebook, for example, are aware how damaging Instagram is for teenage girls.

Jade thinks CGI influencers are a step in the wrong direction as these models are mainly created by men, with the male gaze in mind.

She says: “It's kind of going back in time, looking at the male gaze and their perception of beauty and the standard of beauty that they're putting forward.

“So, in an industry that is trying to be more diverse and inclusive, and tried to move away from size zero, for instance, then suddenly you have these really Amazonian thin, perfect models that are actually unattainable because they're not real is a massive worry.

“Then you've got risks of cultural appropriation and deception.”

Text over me

Remember Kami from the beginning?

She's the world's first virtual Down syndrome model and was created by The Diigitals and Down Syndrome International.

So far, she has 2k followers compared to Ellie Goldstein, the most-followed Down syndrome model, with 88.4k.

However, Kami has a higher engagement rate, of 11.59 per cent, compared to Ellie’s 3.87 per cent.

According to HypeAuditor, "Virtual Influencers have almost three times more engagement than real influencers. That means that followers are more engaged with virtual influencers' content."

This means that Kami’s followers are more loyal - they are more likely to revisit her page and interact with her posts, for example.

Using CGI, the avatar was created by combining photos of over 100 women with Down syndrome.

Real women living with Down syndrome also inspired the CGI's voice and personality.

A panel of women with Down syndrome runs her social media accounts, as she is not an AI.

But, users can message her on Instagram, generating results like this:

The panel explains why they decided to make her look the way she does.

They say: “Kami is an authentic representation of the DS community. She is created and managed by over 100 real young women with Down syndrome, from over 16 countries”.

The team also explained that her name derived from Kamilah, which means perfect.

But, they criticised the unattainable beauty standards of famous Instagrammers.

They say: “We decided to make her because there are so many perfect-looking virtual influencers on IG but zero representation from the Down syndrome community. We wanted to create her to bring more diversity to the virtual world as a champion of the community for girls with disabilities.”

Kami is trying to appeal to a Down syndrome audience, meaning very vulnerable people. So, this could be concerning from an ethical standpoint.

Essentially, people with Down syndrome are told to interact with this online character who, at first glance, appears to be real. This could be confusing and distressing for them.

This is exactly what one Down syndrome model, Beth Matthews, and her self-confessed mom-ager think.

Her mum*, Fiona Matthews says: “I was confused when I saw it, and I didn’t understand the need for it.

“Beth was signed by Zebedee in late summer last year, and because of that, we set up an Instagram account. Because of that, we’ve got to know a lot of the people in the Down’s syndrome community. And I’m just blown away by the diversity, and all the people involved in changing government policy, artists, and things.

“Then, all of a sudden, this computer-generated image pops up saying we don’t think these people are being represented. I just thought, well, hang on? That’s not my recent experience. It’s quite the opposite. I suppose for me, the big question is, why create a computer-generated image if you’ve got the real thing?”

*Fiona spoke on Beth's behalf.

However, some developments are being made in terms of deception.

Meta is looking at an ethical framework for virtual influencers to bring more transparency. The company argues Instagram shouldn't verify them with a blue tick because they're not real people.

In a statement, they said deepfakes might also be problematic in terms of deception.

Have you seen Donald Trump as a cameo in Breaking Bad? Or, Mark Zuckerberg bragging about having total control over people’s stolen data? Or Jon Snow’s apology for the disappointing ending of Game of Thrones?

Answer yes, and you’ve seen a deepfake.

Deepfakes are created when artificial intelligence (AI) is programmed to replace one person's likeness with another in a recorded video.

The TikTok account ‘DeepTomCruise’ is another example of how realistic these creations are. It's hard not to imagine people making videos of politicians saying something which could have considerable real-world consequences. Maybe something bigger than Trump joining Heisenberg on his next drug mission.

Creators don't legally have to state whether it's fake or not, either. Similarly, virtual influencers don't have to say if a post is an ad, unlike their human counterparts. The only country that has regulations over virtual influencers is India. They must “disclose to consumers that they are not interacting with a real human being” when posting sponsored content.

Text over media

Last year, Kristian Sturt, Head of Influencer Marketing for Colossal Influence, researched the long-term ‘pull’ of CGI Influencers.

He explained: “Essentially, I wanted to work out if they were a fad and if not, would it be worth working with one or maybe even developing one?

“I found that in almost any case, there are better creators to work with and that, unless there were a ground-breaking development in the field, CGI influencers would struggle to grow from their initial push.

“I think CGI influencers had a huge impact when they came about because of the shock factor, and while some have managed to stay at the top level when you compare that to real people, it’s just not a contest.

“Some basic research right now for me has confirmed that. Most of the literature on CGI influencers is from between 2018 and 2020. Lil Miquela still appears to be the biggest, and although I’ve noticed some niche ‘new’ CGI influencers, it looks like they’ve peaked.”

But, Jade has seen recent developments in the modelling industry which are pointing toward a CGI takeover.

She participated in a few projects with the Fashion Innovation Agency at the London College of Fashion, where she was scanned and created as a photo-realistic digital version of herself.

In the wider fashion world, models are being virtually scanned so brands can manipulate them.

The ex-model says: “I realised it has a lot of kind of value, especially within the modelling industry.

“And then I kind of realised that many models were scanned on shoots. And they weren't aware.”

“They didn't understand the technology; the agencies didn't understand the technology, and the contracts in place weren't suitable to protect the model. And the data that was created from the scans. And, you know, who owns that, that avatar or digital version of themselves? Where is that data stored? Is it protected? Is it getting transferred to a third party without the knowledge of the model?”

Jade is working with several agencies to tackle this but ultimately thinks CGI influencers could be the future with an amalgamation of these scanning technologies.

“I think it will happen. But that's why I strongly believe that we need to find a place within the metaverse for digital versions of models like human beings that have been digitised.

“There are human mannerisms and nuances that can't be replaced with a CGI model. And I think brands really need to hold on to that kind of human quality. I think they'll realise that.

"At the moment, it's a bit of a gimmick, and they'll probably definitely test the CGI version at one point. But I think they will realise that it's not connecting to their consumers as much as they would hope as a human being would.

So, whether or not there’ll be a CGI influencer takeover, it sure seems like it will be a diverse one. As Fiona says: "Diverse change in both worlds is needed. It can only happen once it embraces diverse people themselves."