Mukbangs: Food for thought

Can watching others eat help repair your relationship with food?

When you hear the word ‘mukbang’, what is the first thing that comes to mind?

Some may imagine a person sitting in front of a camera, eating an entire spread of artificially-coloured food and making loud and over-exaggerated noises.

In this case, creators like Nikocado Avocado may spring to mind. Known for crying, screaming, destroying his food and even fighting with his partner in videos, it is easy to see why he gets so many views.

But for others, mukbangs in their truest form are helpful, relaxing and seen as a safe space. Many people have found success in repairing their tarnished relationship with food, and even going as far as to say they have helped with their eating disorder recovery.

To understand why all of this might be, the question needs to be asked:

What actually is a mukbang?

The mukbang

In South Korea, single-person households make up 31.7% of the country’s population as of 2020, which has been steadily on the rise. In the UK, these figures are similar, at around 29.9%.

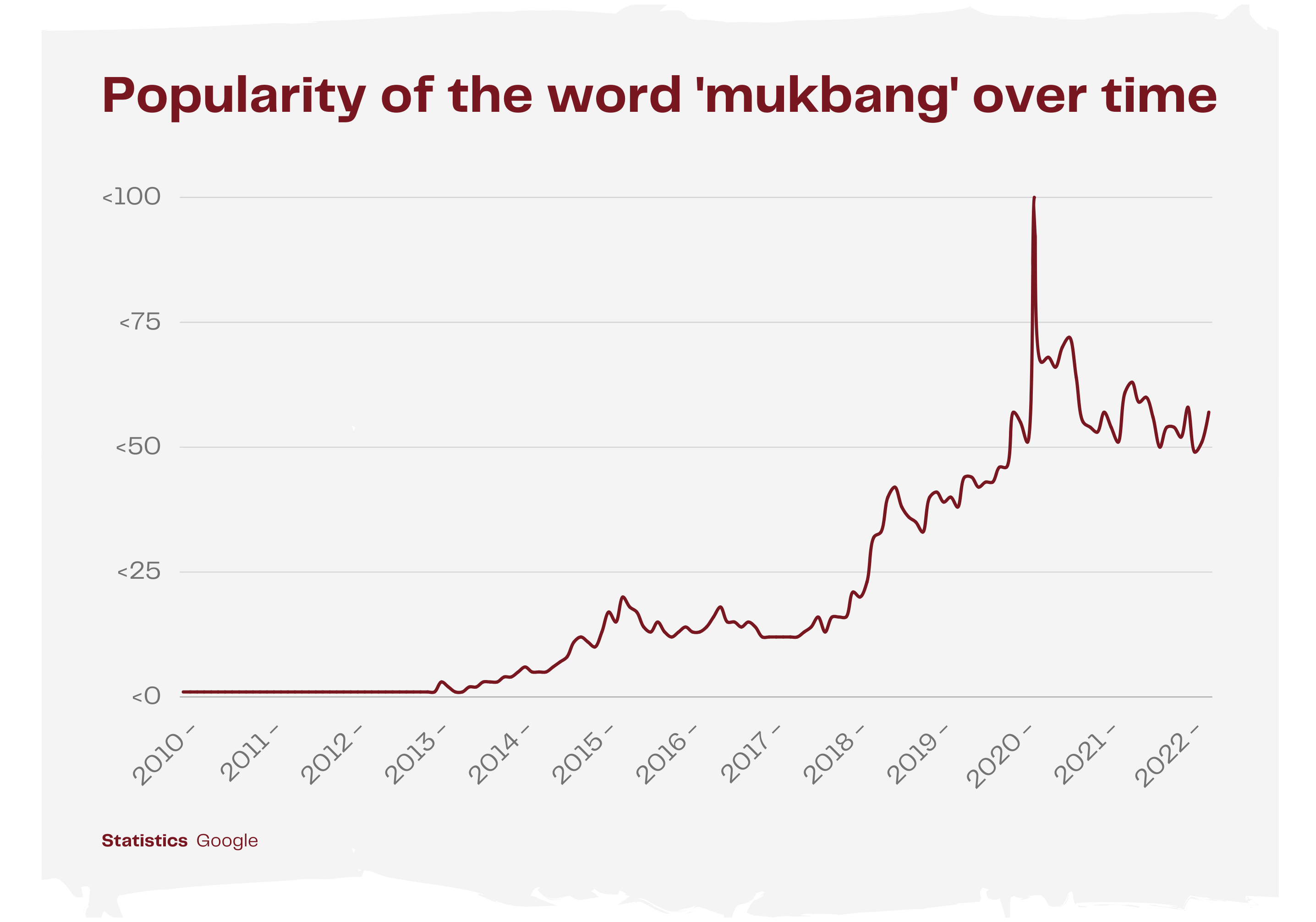

So in 2010 that this idea of broadcasting meals to others was created for a new sense of ‘togetherness’ was born. It first prevailed on popular streaming sites like Afreeca TV and Twitch, and soon the West would recognise its popularity and bring it over to YouTube just a few years later.

It was at this point when creators like the aforementioned Nikocado Avocado, the self-proclaimed “king of mukbangs” with over 3.1 million subscribers, recognised their virality and made it their own. He is a key example of how Western creators have taken mukbangs and exaggerated them to the point where they are no longer true to their original concept.

The term ‘mukbang’ is a combination of the Korean words “muk-ja” (let’s eat) and “bang-song” (broadcast). Essentially, a mukbang consists of a host eating food while interacting with their audience. It originated as a way for people to deal with loneliness while they ate, as the act of eating is seen as a very communal and social activity in many Asian countries. But newer generations are currently facing an alternate reality.

With over one million videos on YouTube and counting, new sub-genres are inevitable. The most prominent example is the integration of mukbangs into the realm of ASMR, where people prioritise the visual and audio aesthetics of the food in order to create a certain response from their viewers.

There are, however, both creators and consumers of mukbangs who have found great benefits in watching and creating them, but before understanding their impact, it is important to understand just what an eating disorder actually is.

The eating disorder

An eating disorder is a mental health condition where food is used to cope with feelings, emotions and other situations. Eating too much or too little as well as being in a constant state of worry over your weight are a few examples of unhealthy eating behaviours.

It is estimated that around 1.25 million people in the UK have an eating disorder, and it can affect anyone at any age.

Clinical advisor for Beat, Dr Richard Sly, said in an interview: "Eating disorders are complex mental illnesses, and while they manifest in disordered behaviour around eating, the way the sufferer treats food is less important than the thoughts and feelings that influence their behaviour."

While not everyone finds watching others eat interesting or helpful, and in some cases quite harmful, there is a lack of conversation surrounding its positive effects.

The creators

19-year-old Elle Morrison posted her first video to her YouTube channel in 2019.

She states in the video titled ‘Anorexia recovery - going “all in”’ that it was her third day in recovery from anorexia.

Elle was bounced between CAMHS departments in the early stages of her eating disorder. She was unsure if it was her depression that was causing it, or if it was the other way around. Eventually, she stuck with the team trained to deal with eating disorders, and they helped her as much as they could.

“I met this wonderful lady who helped me a lot. She has definitely helped me with recovery. I think mainly because I saw her not as my CAMHS worker, but as a friend I go to for help, and that made it feel less intense. You don't feel like you go there for help, you just go for a friendly chat, which I think really helped me.”

It also led to her discovering something new about herself and receiving a new diagnosis: PMDD.

Every month, the week or two before her period, she gets an “unnecessarily really bad chemical imbalance” in her brain, where suicidal thoughts are heightened and eating disorders are made to feel more severe, but after a week “you’re back up and you're fine again.”

Fast forward to now in 2022, she has amassed over 8,000 followers across her YouTube channel ‘Let’s Do This Elle’ and her Instagram. Even after recovery, she continues to create videos and content for others in the hopes of helping anyone who may be struggling too. This, of course, includes mukbangs, alternatively called ‘eat with me’ videos.

During her recovery, Elle found herself frequently watching other people eat. At first, she was hesitant. She didn’t understand the concept and found herself questioning it completely.

“I used to hate people who would chew and talk at the same time. I just didn’t get it. But now I see it in a completely different way.”

Elle watched mukbangs to escape from feeling isolated, as recovery from an eating disorder can often make you feel. There was a channel she watched where another girl simply ate her breakfast and chatted away to her camera. After watching this as someone who struggled with breakfast, she realised it had helped her, and thus was inspired to do the same on her channel.

She does, however, see the negatives. Everyone’s experiences are different and no one can say what will work for one person or the other. While it can aid people in recovery, there also needs to be the assumption that it isn’t one-size-fits-all.

“If it can at least help one person, that’s my job done. I just want to make people feel like recovery doesn’t have to be as hard as it seems… like you can eat breakfast! You can do this, you can do that. You can do it.”

“I was probably about 13 or 14 when I first found mukbangs,” says now-24-year-old Allyson Cummings.

In her youth, she was grounded a lot in high school and found herself surfing the web constantly, especially YouTube.

“The first video [of a mukbang] I saw, I instantly loved.”

Known as @biggirlbigworld on TikTok and with over 70,000 followers, Allyson creates short videos of her eating delicious meals that she either prepares herself or orders from restaurants. While some of her videos consist of no talking and just eating, others include simple conversations with her audience, asking questions about their days and telling them about her own.

Allyson’s relationship with food varies day by day. From around age 11, her body image started to deteriorate. She feels it was both internal and external influences that affected her so young.

“It’s plain to see that, here in America and every other country, being skinny is the trend and ‘overeating’ is ugly. Men and society only desire skinny women. It’s sadly ingrained in a lot of people from a very young age. My mother also struggles from an eating disorder and I think I picked up on that too.”

After struggling with a binge eating disorder for a large portion of her life, she found mukbang-ing as a way of rediscovering all the positives that come from a good meal.

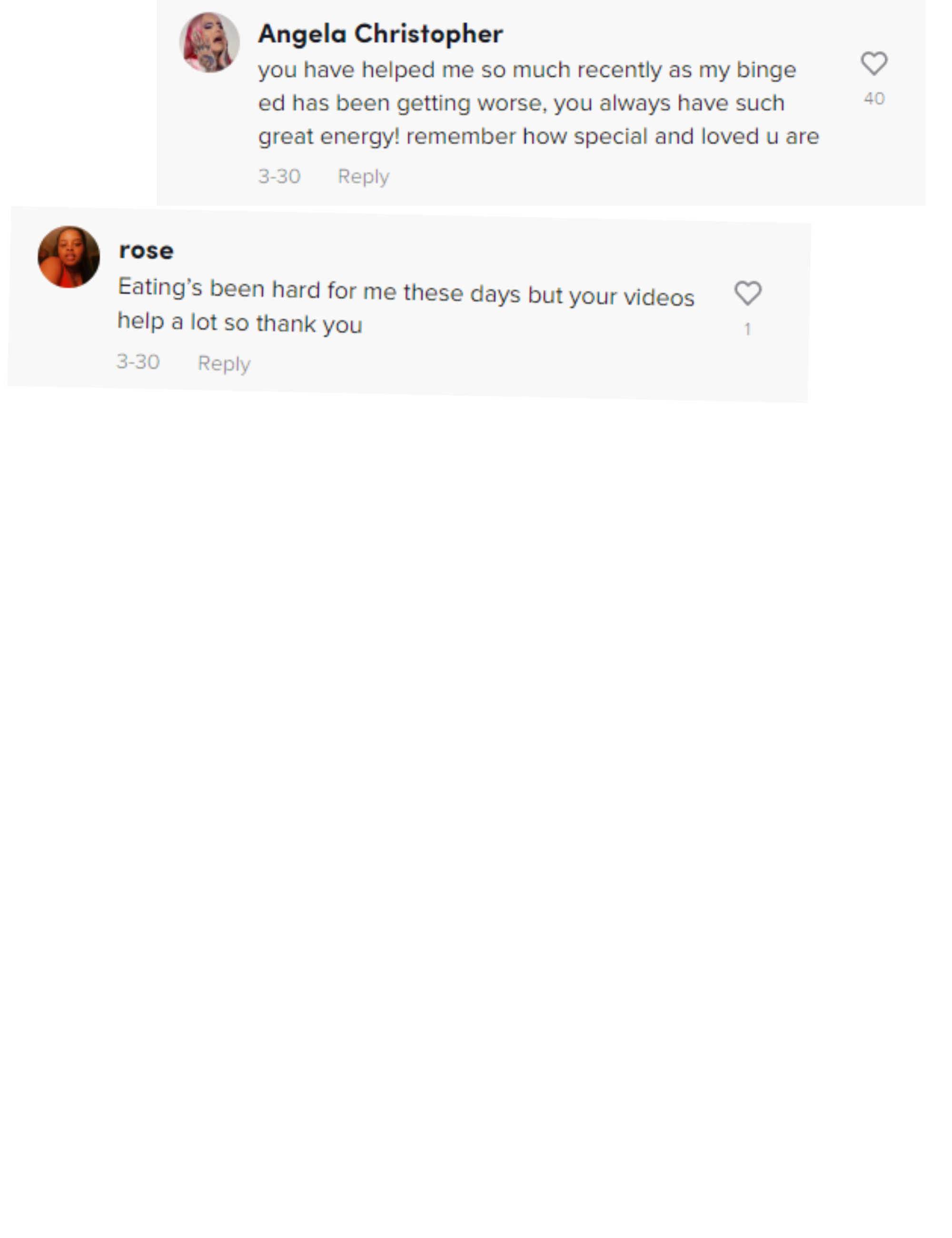

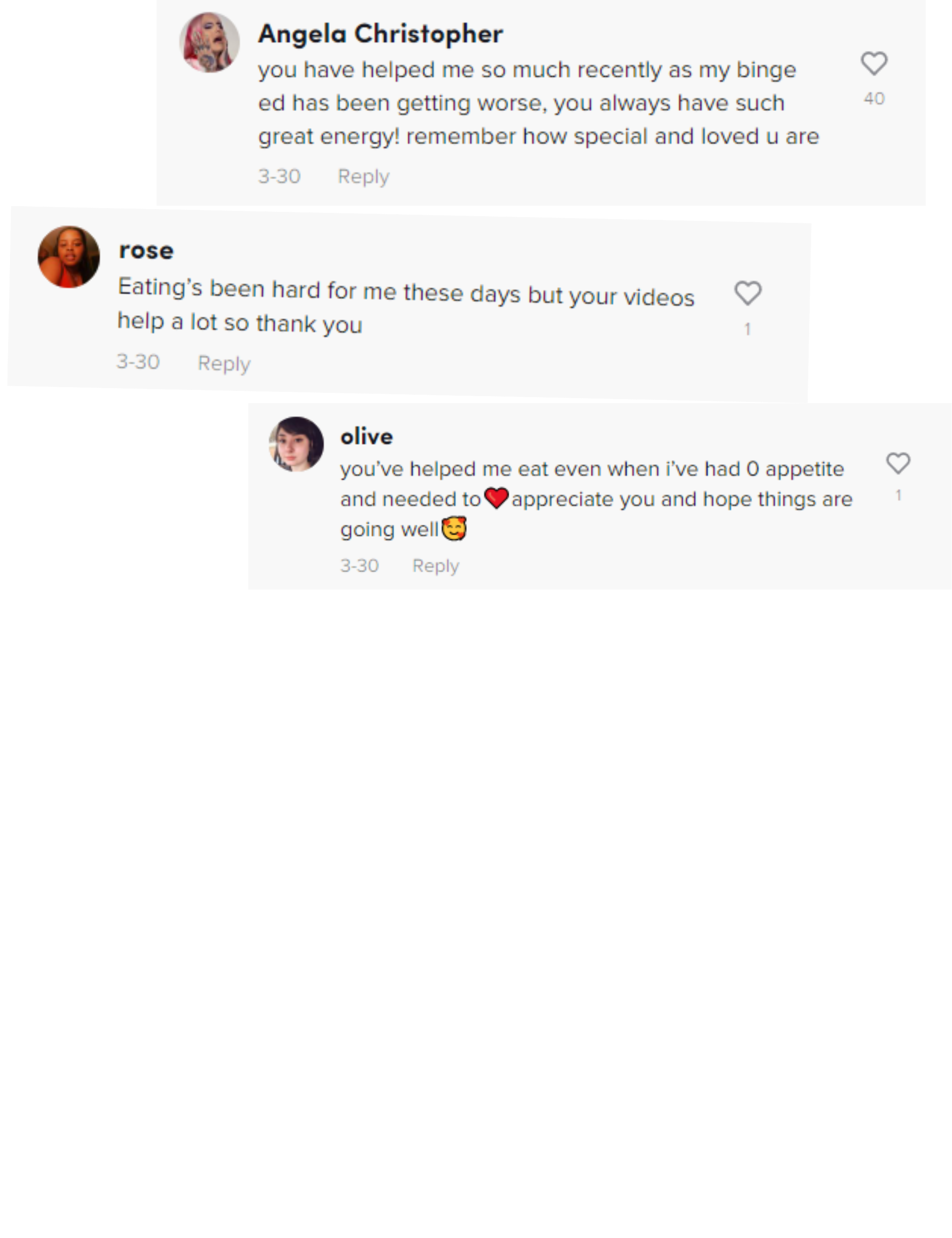

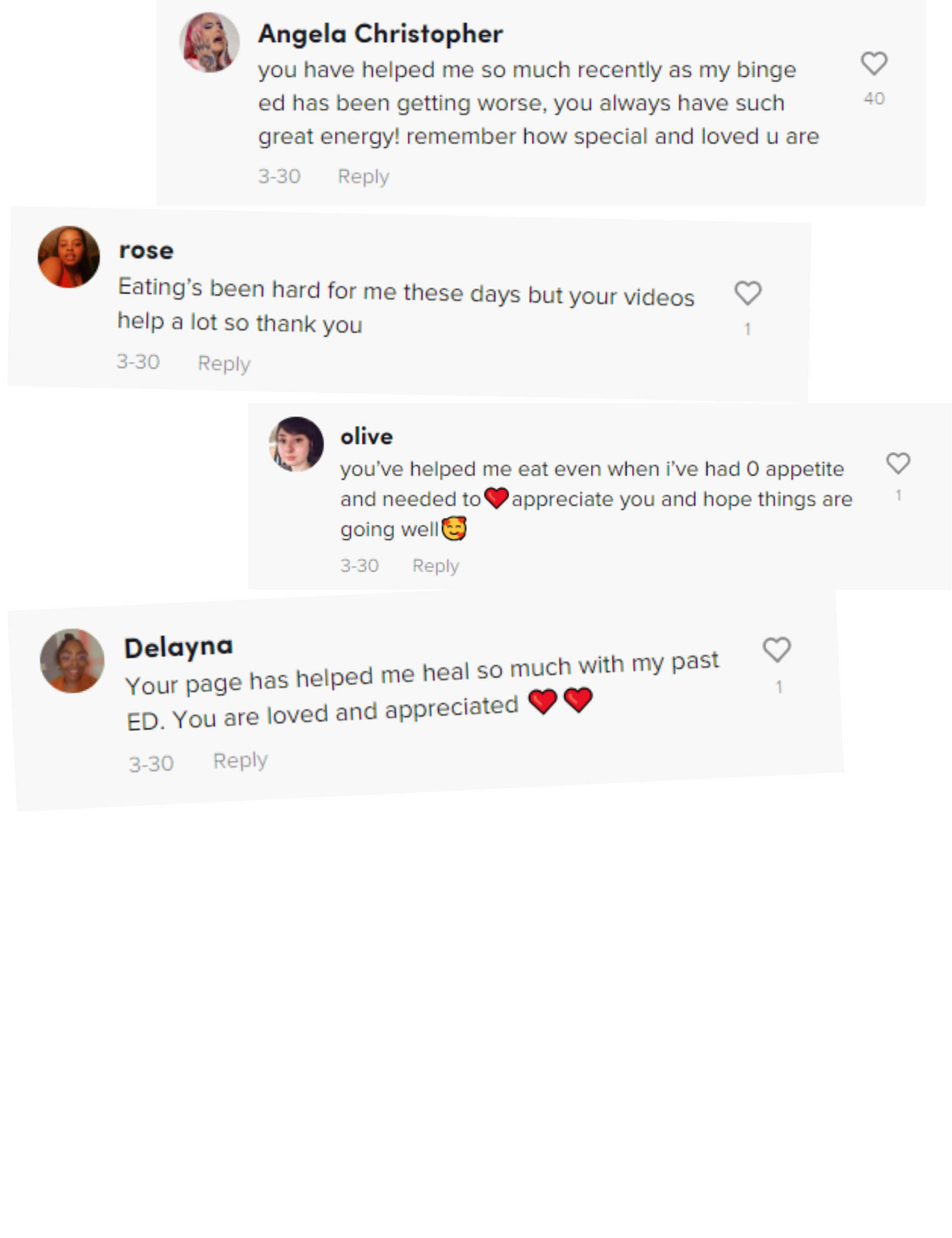

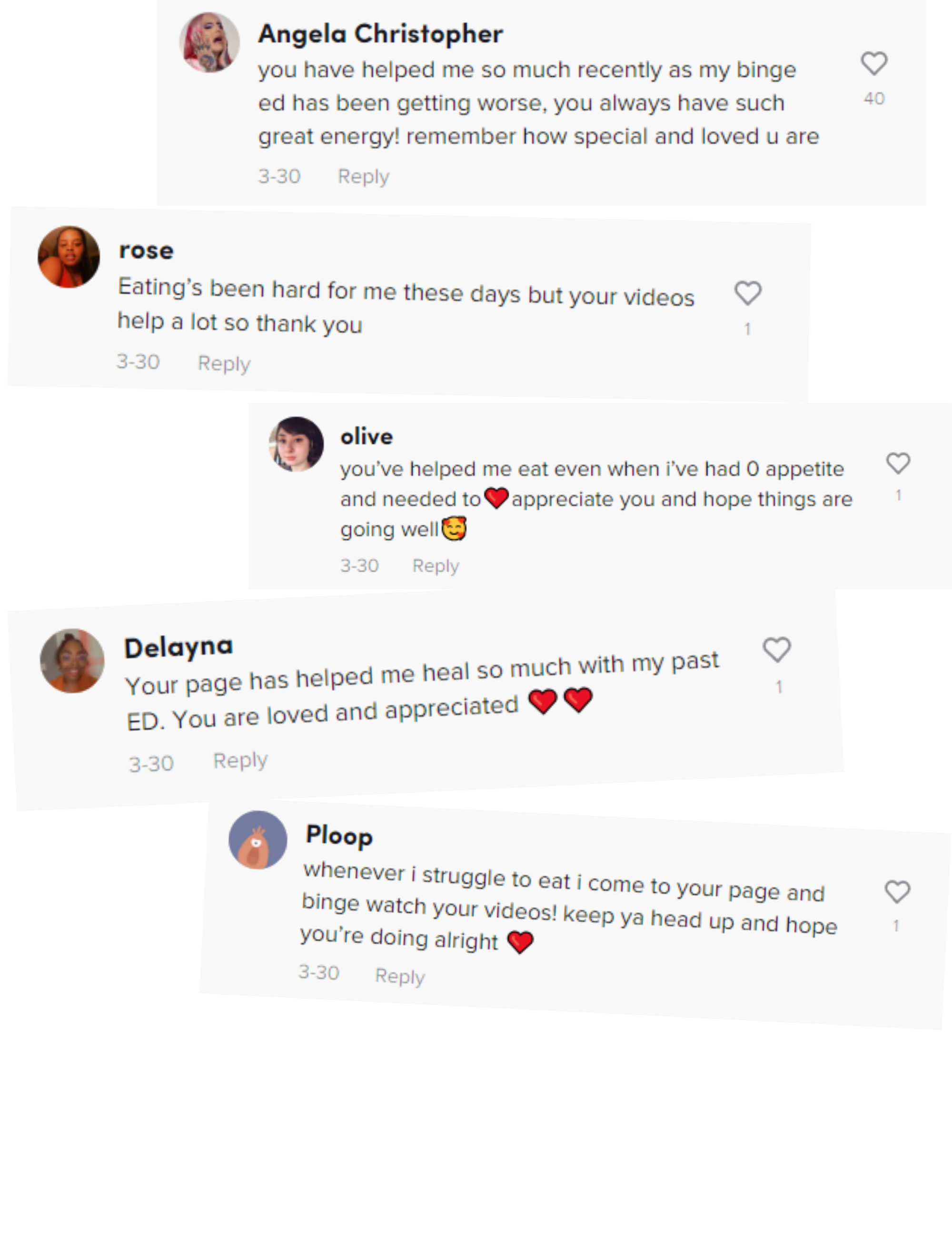

“While I am still struggling on a daily basis, [creating my videos] does get me out of bed. It gets me to go make a meal. I started making videos just because I loved watching them, but when I started receiving positive comments saying how I’d helped them, it made me want to post more. And honestly, it keeps me accountable for eating some days as well.”

Allyson believes that her videos can be helpful to many, but understands that they’re not for everyone. She emphasises that people have their own free will, and can scroll past her videos if they do not interest them.

“People on the internet get way too triggered about other people’s lives.”

But at the end of the day, she wants her audience to understand the importance of food. It’s not simply a necessity for survival, but something bigger.

“Food is fuel. Food is love. Food is community. Food is meant to be shared with friends, family and strangers. Listen to your body, it will tell you everything you need.”

The consumers

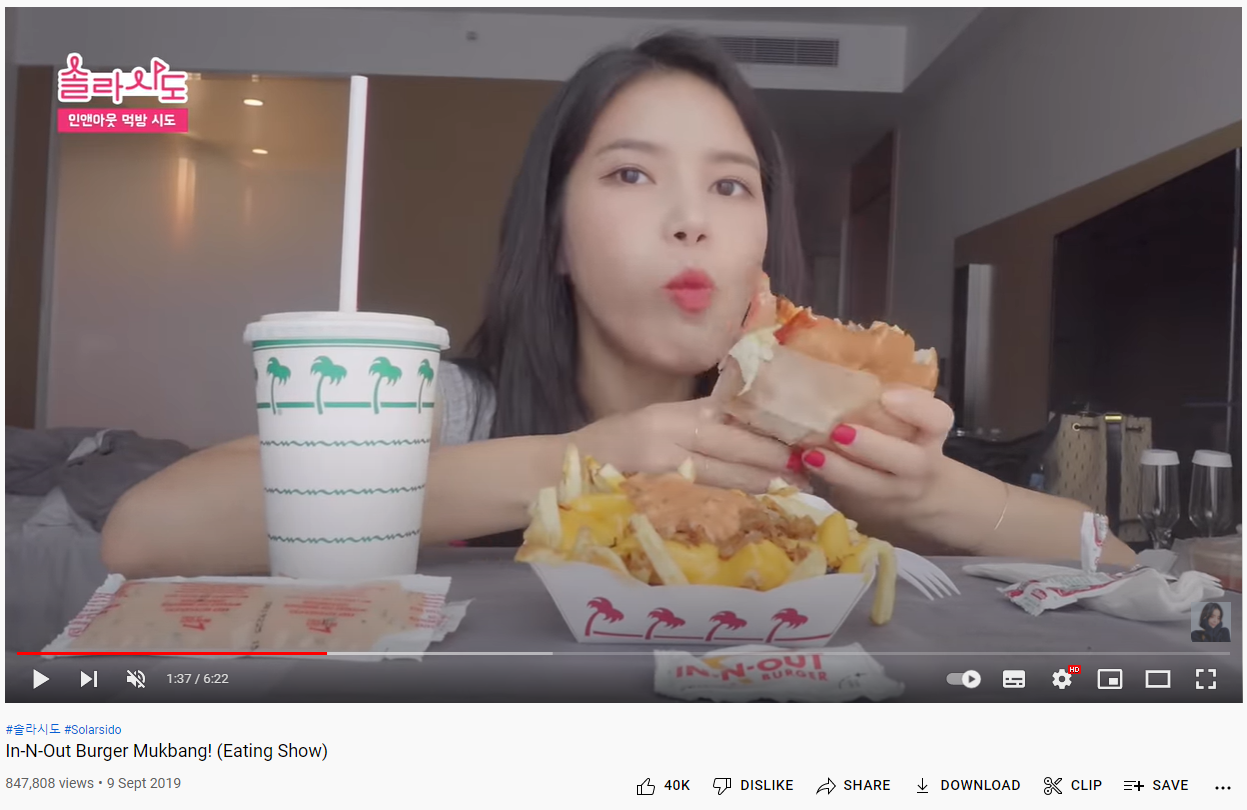

Nera Curman discovered the world of mukbang-ing by accident, and in a way that may seem unconventional to most: through K-pop.

“I’m a big fan of the K-pop group MAMAMOO,” she explains.

“I’ve been following them for years now, and my favourite member is Solar.”

The 25-year-old had never indulged in anything amongst the likes of mukbangs before, but when a member of her favourite group opened up a YouTube channel and eventually began uploading mukbangs, Nera was curious. She would support anything Solar uploaded including her eating videos, and with time she worked out that they were helping her appetite.

While Nera does not suffer from an eating disorder, she has issues with hyperthyroidism. It tainted her whole relationship with food dramatically. She knew she would have to eat but would find it incredibly difficult.

From left to right: Moonbyul, Solar, Wheein and Hwasa

From left to right: Moonbyul, Solar, Wheein and Hwasa

Screenshot of a mukbang video by Solar

Screenshot of a mukbang video by Solar

“I couldn’t chew, I couldn’t swallow. It was just something I started to do out of pure necessity.”

After switching jobs, her breaks would land around mid-morning, which was also the period for eating that she suffered with the most. But with time, she noticed herself “eating better, chewing better, and swallowing easier” while watching her.

Like many people of her generation, Nera has grown up consuming online content and feels she has become the person she is today because of the creators she watched and supported. When she first stumbled upon a mukbang, she thought they were absurd and did not understand the appeal nor why so many people chose to watch them.

But when she realised the videos by Solar were helping, she ventured into other creators’ content to see if they would have the same effect, but she was surprised to find the opposite.

With other mukbang-ers, she found they were missing the part where she simply forgot she was eating. She concluded that it was her pre-existing admiration of Solar that encouraged her to view mukbangs in a different light.

“I was emotionally involved with this person, so I feel it was easier to bypass my prejudice towards that type of content. It happened with K-pop for me as well; it was completely accidental.

I didn’t even realise I was listening to K-pop at first and I never would have touched it otherwise, even if people told me, like: ‘Go and watch it! It’s so cool! You’ll like it!’”

Catherine Arnold’s relationship with food is “complicated to describe.”

Since she was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis at 5 years old, she has always struggled with eating.

“My body won’t process most foods, and it reacts horribly to almost everything. Because of this, I’ve developed a trauma-reaction response to eating in which I restrict myself in order to not flare up.”

Catherine didn’t realise she had an eating disorder until around 2020 when she got a dietician. They never put an official name on her disorder, only informed her that it was a “restriction trauma reaction”. Because she is “scared of eating”, she believes this is why mukbangs are so comforting for her.

“I feel like, in a way, I’m eating through them.”

While having an understanding that people can react differently to these videos, she finds it comforting and a way to help reduce her anxiety, but agrees that some people do not take the mukbang genre seriously at all.

Many bigger mukbang creators tend to exaggerate mukbangs to the extreme. Eating live octopi, hitting all of the food off of the table and creating unnecessary drama within the community for clout are a few examples of how many creators are giving genuine mukbang-ers a bad reputation.

“Some people take advantage of it. Some creators just want to make people happy, but some have made it into a caricature.”

Everyone is different, and mukbangs are a double-edged sword.

There is research to suggest that mukbangs can be harmful rather than helpful to those with disordered eating, and are used as a negative coping mechanism rather than something to bring comfort and ease.

But the mukbang’s potential to be either beneficial or detrimental to someone’s health depends heavily on the ability of both creator and consumer to exercise moderation.

While no conclusion can be made as to whether it is definitively one or the other, it is clear to see that there are both positives and negatives.

Try watching a mukbang for yourself and find out!

It must be noted that watching mukbangs is not a replacement or alternative for getting help. If you think you may have an eating disorder, see a GP as soon as you can.