Dreaming of a

Great Sheffield Salmon Run

Every winter, millions of Atlantic salmon set off from the North Sea to the rivers of their birth.

Before the 1850s, salmon would swim thousands of kilometres while braving the forces of nature, to reach the shallow waters of the River Don where they can lay their eggs in the gravel.

But Industrial Revolution led to widespread pollution which decimated all forms of life. The river was declared as "ecologically dead".

A "Salmon of Steel" project which began more than 20 years ago, has worked to bring the fish back to the centre of the Sheffield.

Now, they are here to stay.

Chris Firth MBE, a trustee at the Don Catchment Rivers Trust, reflecting on what the return of salmon to Sheffield means to him.

Chris Firth MBE, a trustee at the Don Catchment Rivers Trust, reflecting on what the return of salmon to Sheffield means to him.

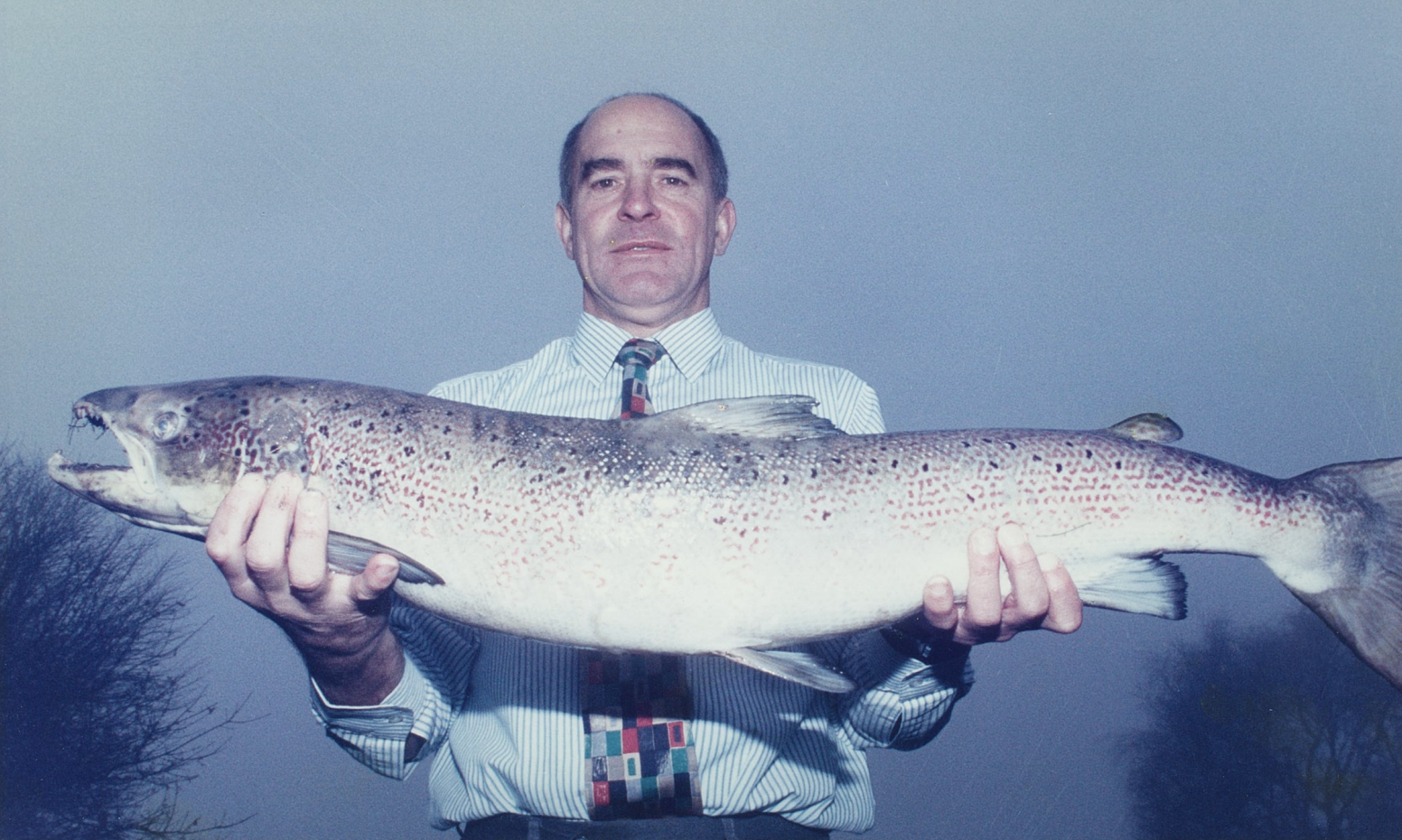

New Year’s Eve, 1995- Chris Firth remembers spending the last minutes of the year digging a hole through heaps of snow in his back garden.

The "treasure" he needed to bury was a three-feet long salmon he had found washed up on the banks of the River Don in Doncaster, following a tip-off from a local resident.

“It was late at night and the office was closed,” says Firth, 77, who was a fishery officer at that time.

“I mean, all I had at home was a ‘normal’ freezer and it was not enough to put a fish that big to preserve it.”

Chris Firth MBE in 1996 with an 11lb salmon he had found on the River Don at Doncaster. This discovery inspired the various environmental agencies to work towards building a sustainable salmon population in the river after an absence of nearly 200 years. COURTESY ©DCRT

Chris Firth MBE in 1996 with an 11lb salmon he had found on the River Don at Doncaster. This discovery inspired the various environmental agencies to work towards building a sustainable salmon population in the river after an absence of nearly 200 years. COURTESY ©DCRT

Two days later, he brought the salmon to a laboratory in York. An autopsy revealed the fish had lived in the River Don for at least five months before dying of natural causes.

The findings, according to Firth, suggested the water quality of the River Don, once dubbed as “Europe's dirtiest river”, had "improved massively". After all, salmon require the cleanest and most pristine conditions to survive.

"Since a salmon was found downstream of the River Don in Doncaster," he thought to himself, "does this mean it's possible they could return back to centre of Sheffield to lay their eggs for the first time since the 1850s?"

More than 20 years later, juvenile salmon were seen swimming in the River Don this past winter.

Chris Firth's "impossible dream" has come true.

Dr Deborah Dawson, a conservation geneticist at the University of Sheffield, credits agencies such as the Don Catchment Rivers Trust (DCRT), Yorkshire Water, the Environment Agency and local authorities on their efforts to guide the Atlantic salmon back “home” to their historic spawning grounds in the centre of Sheffield.

“Whether it’s campaigning, fundraising or designing and building (fish passes), it’s lovely to see different people coming together to share their expertise and knowledge,” she says, “decades of dedication trying to improve the river and they’re doing a fantastic job.”

From left:Professor Vanessa Toulmin (The University of Sheffield), Sally Hyslop (DCRT), Anthony Downing (Environment Agency), Chris Firth MBE (DCRT), Dr Deborah Dawson (The University of Sheffield) and 'Salmon of Steel' sculpture artist Jason Heppenstall ANDY KERSHAW VIA TWITTER

From left:Professor Vanessa Toulmin (The University of Sheffield), Sally Hyslop (DCRT), Anthony Downing (Environment Agency), Chris Firth MBE (DCRT), Dr Deborah Dawson (The University of Sheffield) and 'Salmon of Steel' sculpture artist Jason Heppenstall ANDY KERSHAW VIA TWITTER

Meanwhile, Firth believes the rejuvenation of the River Don is due to nature's ability to heal itself over a period of time.

“Just look at the the Chernobyl disaster as another example. Even when there’s incredible levels of devastation, nature has reclaimed that place and wildlife is coming back,” says the author of '900 years of the Don fishery: Doomsday to the Dawn of the New Millennium'. "But we must give it the opportunity to do so.

“Our work with the River Don gives me hope that one day we can start to reverse a lot of the damage done to the environment and eventually save the planet.”

The River Don was once declared "ecologically dead" after it was riddled with pollution from Sheffield's mining and steel industries.

Chris Firth was born 25 miles downstream at Doncaster in 1944. Growing up, the river was his playground.

"For the first 29 years of my life, I witnessed just how disgraceful and disgusting the River Don was"

When I was a kid, my mother used to say: “Whatever you do, do not go near the River Don."

“Well, I can swim,” was my reply.

And she would say: “It's nothing to do with being able to swim. If you fall into that river, I’ll have to take you to a hospital, and your stomach will be pumped to get all the chemicals out.”

Now believe me, the idea of somebody shoving a pipe down my throat was not something I was attracted to.

I used to walk with my friends down to the River Don. Boys being boys, we were always up for a bit of mischief.

I remember throwing stones in the river, and we would see "rings" forming up. We used to think they were fishes rising to the surface.

But in reality, they were gas bubbles from waste materials that the factories and mills had dumped into the water.

There were also grey and brown foam bubbles floating down the River Don (They were formed from detergents that were discharged into the river). When it was windy, they were like clouds drifting in the air. My friends and I used to stand on the bridge with our sticks and whack these bubbles. They smelt really bad.

Even though I had witnessed just how disgraceful and disgusting the River Don was, it was still a fascinating place to me.

I wanted to be a gatekeeper of the river.

COURTESY ©DCRT

COURTESY ©DCRT

In the early 80s, the River Don and its tributaries were still in an appalling condition. They were totally dead and devoid of any vegetation.

One of my responsibilities, as a fishery officer based in Doncaster, was to identify signs of life in the rivers, by carrying out electrofishing surveys

Discovering that one tiny stickleback in a river so dirty and polluted was my driving force.

It gave me the confidence to believe there was a chance of bringing life back to the River Don.

By the mid-80s, a series of environmental legislations had forced local authorities to act on cleaning the River Don.

After the discovery of an Atlantic salmon in 1995, the various environmental agencies began exploring what else they can do to help the fish species return back to the centre of Sheffield to spawn.

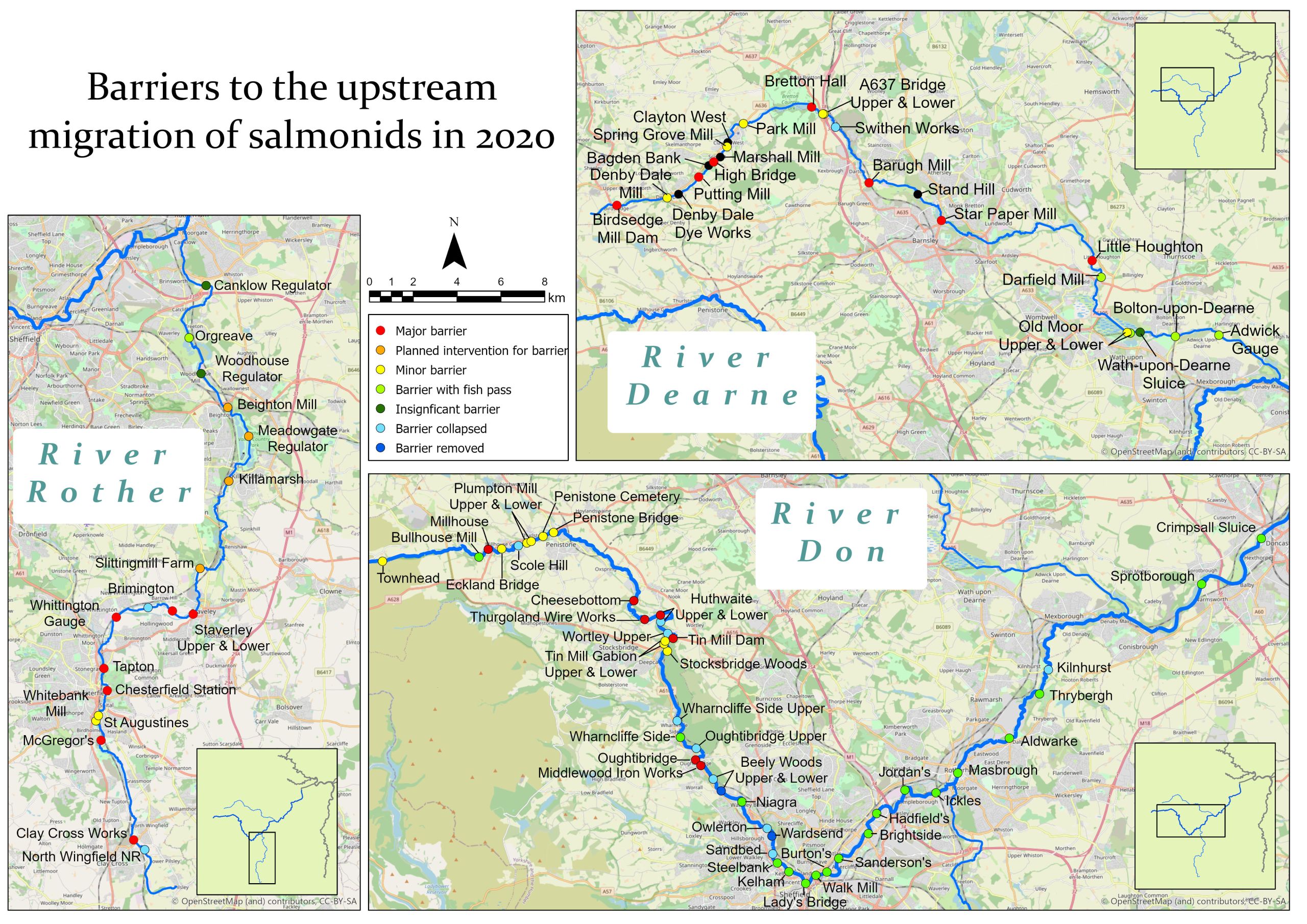

Next on the agenda: Dealing with weirs and other barriers such as dams and sluices.

Walk Mill Weir on Effingham Street, Sheffield

Walk Mill Weir on Effingham Street, Sheffield

The origins of weirs can be traced hundreds of years ago when the Normans built them to harness energy from rivers.

During the Industrial Revolution, dozens of weirs were used to divert water to the factories and mills, which in turn fuelled Sheffield's early steel industry.

Lady's Bridge Weir in Sheffield City Centre, 1978. SHEFFIELD NEWSPAPERS LTD VIA PICTURE SHEFFIELD

Lady's Bridge Weir in Sheffield City Centre, 1978. SHEFFIELD NEWSPAPERS LTD VIA PICTURE SHEFFIELD

However, a report published by the Environment Agency revealed their presence created an 'obstacle course' for the salmon, blocking the fishes' migratory route to their spawning grounds upstream of Sheffield and in the Pennines.

The best outcome, the report added, was to demolish these weirs. They were no longer in use since most of the factories and mills were gone.

But some of the weirs had listed status due to their historical attachment to Sheffield's industrial past, according to Anthony Downing, the Environment Agency's catchment co-ordinator for the Don and Rother.

The solution? By Installing fish passes on them.

"It's about getting the balance right," he says, "we want to improve the ecology of the River Don and its surroundings, but it's also important to acknowledge the historical significance and value of weirs in this city."

Masbrough Weir in Rotherham.

Final piece of the jigsaw: The Masbrough Weir fish pass was completed in June 2020. Salmon can now move freely through the River Don to lay their eggs at the spawning grounds in the centre of Sheffield, for the first time in nearly 200 years.

Ever since the first obstacle, Crimpsall sluice in Doncaster, was removed in 2000, agencies such as the Don Catchment Rivers Trust, the Environment Agency, Yorkshire Water, the Canal & River Trust and Sheffield City Council have installed fish passes on 17 more weirs.

The next objective is to remove more obstacles in the River Don and its tributaries so that salmon will be able to reach further to the spawning habitat in the Pennines, according to Dr Ben Gillespie, a technical specialist at Yorkshire Water.

The next phase of the 'Salmon of Steel Project': Installing fish passes on weirs further upstream of the River Don and the rest of its tributaries (River Rother and River Dearne). This will allow the salmon unobstructed access to lay their eggs in the shallow waters at the Pennines COURTESY ©DCRT

The next phase of the 'Salmon of Steel Project': Installing fish passes on weirs further upstream of the River Don and the rest of its tributaries (River Rother and River Dearne). This will allow the salmon unobstructed access to lay their eggs in the shallow waters at the Pennines COURTESY ©DCRT

While the last winter had seen the presence of juvenile salmon in the River Don which indicates fishes are reproducing in its waters, Gillespie, who has been part of the "Salmon of Steel" project for more than six years, feels this should not be the only measurement of success.

"It's great that people are excited to find salmon (in the River Don), he says, "but it's about all fish species and everything else that's living in there."

Removing obstacles and installing fish passes on the River Don will not only benefit the Atlantic salmon, but also other migratory fishes, such as grayling (seen above) and trout. COURTESY ©DCRT

Removing obstacles and installing fish passes on the River Don will not only benefit the Atlantic salmon, but also other migratory fishes, such as grayling (seen above) and trout. COURTESY ©DCRT

A change in public perception towards the River Don is another measurement of success that Sally Hyslop of the Don Catchment Rivers Trust (DCRT) can attest to.

People are beginning to fall in love with river, says the community engagement officer.

"When we first asked the community to describe the River Don in three words, all we got were: 'Horrible', 'dirty' and 'disgusting'," says Hyslop. "We asked them again 3 years later. They have changed to 'beautiful', 'clean', and 'safe'.

Sally Hyslop (far left) and her colleagues at the DCRT. She says activities such as litter picking helps foster a community spirit to care for the river. COURTESY ©DCRT

Sally Hyslop (far left) and her colleagues at the DCRT. She says activities such as litter picking helps foster a community spirit to care for the river. COURTESY ©DCRT

"A lot of people felt the River Don was not safe to go. So we're running activities like litter picking to make it more welcoming, and this encourages people to care about about the place."

Hyslop's colleague, Chris Firth, shares her sentiments. After all, he had lived through a time when the River Don was at its worst.

The DCRT trustee takes pride in knowing the "Salmon of Steel" project has helped undo some of the damage caused by previous generations to the river.

"People are beginning to appreciate and recognise the value of the river. Now, it's a fundamental part of their lives," says Firth. "There's nothing more relaxing than walking along the River Don and listening to the sound of water."

Even though the River Don's revival is heralded as an "environmental miracle", Firth remains concerned.

"The River Don is essentially an urban river. There's always going to be risks associated with its future," he says, "I fear there'll be temptation to allow developments in the city to insidiously damage the environment once again, just like how our ancestors had done so.

"It'll erode what we've achieved so far."

Developments near the River Don, such as a planned Forge Island leisure quarter in Rotherham (above), will be beneficial for tourism and the local economy, says Chris. But he adds they cannot be at the expense of polluting the river. COURTESY ROTHERHAM BUSINESS

Developments near the River Don, such as a planned Forge Island leisure quarter in Rotherham (above), will be beneficial for tourism and the local economy, says Chris. But he adds they cannot be at the expense of polluting the river. COURTESY ROTHERHAM BUSINESS

But if discovering of a salmon on New Year's Eve 26 years ago has taught Firth anything, is that he always believes in the resilience of nature.

And an Atlantic salmon's ability to swim thousands of kilometres without food, leap through waterfalls and avoiding hungry otters lurking on the river bank, just so it can return to the place of its birth- The City of Steel.

Like Firth, Dr Deborah Dawson is also dreaming of a Great Sheffield Salmon Run.

"I wish all these agencies continue with their success in removing more weirs and building fish passes on the River Don. So we'll get to see salmon every winter, between November and February," says the conservation geneticist.

"It would be nice if kids can call me and say, 'Look, I can see them jumping on the river. It's so beautiful.'

"That's my hope for the future."