Sheffield's African War

Hundreds of Sheffield citizens worked, fought and died across South Africa in the Boer Wars. What are their stories - and why do they matter?

The South African Wars

The first week of April 2025 will see a little-marked anniversary pass by - the beginning of the end of the second, and final, Boer War.

In the late Victorian era, British imperial armies fought against Dutch-descended republican settlers - the ‘Boers’ - for supremacy in southern Africa. The wars, the last of which was fought from 1899 to 1902, were messy and brutal, and civilians on all sides, not least the indigenous Africans, paid the price. On the home front, meanwhile, warfare in South Africa shaped everything from street names and civic architecture to emerging plans for state healthcare.

But what remains of this legacy, and what does it have to do with modern Sheffield? To find out, I spoke with civic historians, did research of my own - and uncovered some little-known tales of the Steel City at the heart of empire.

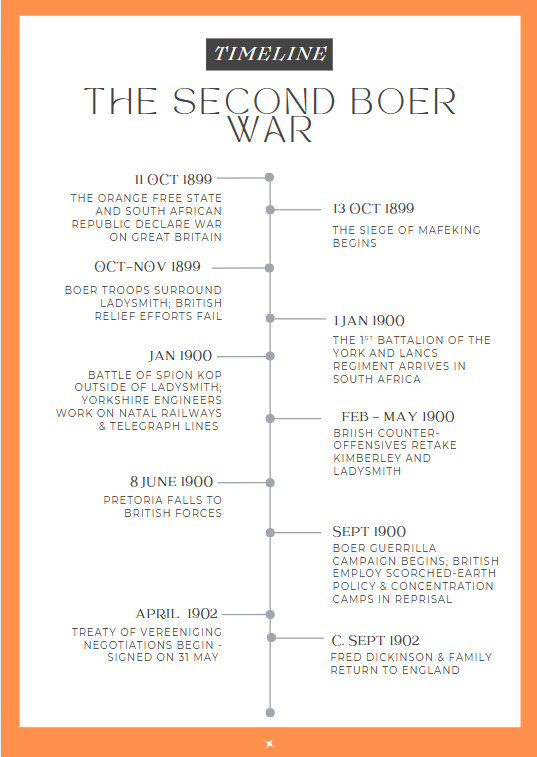

A timeline of the Boer War, and Sheffield's involvement with it.

A timeline of the Boer War, and Sheffield's involvement with it.

Family Stories

The war transformed the lives of thousands of Sheffield military men - but not just them alone.

Joanne Spina has been carrying out family history research for years - and uncovered plenty of secrets and surprises, all the way back to the fall of the Roman Republic. More recently, however, the South African War would leave a lifelong impact on her maternal great-grandfather, Frederick Dickinson.

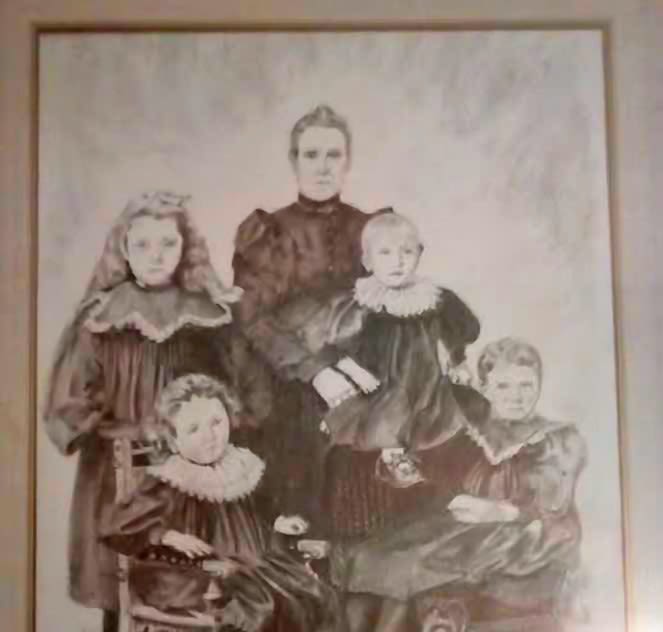

A farrier, Fred served in the Royal Engineers. And shortly after leaving, his pregnant wife, Luci Ellin, decided to follow him to South Africa with their two children.

Joanne said, “She just took the two kids, and she went down to London and boarded a ship at Tilbury Dock for Africa - which, if you consider the year, that’s not really the done thing for ladies to do.”

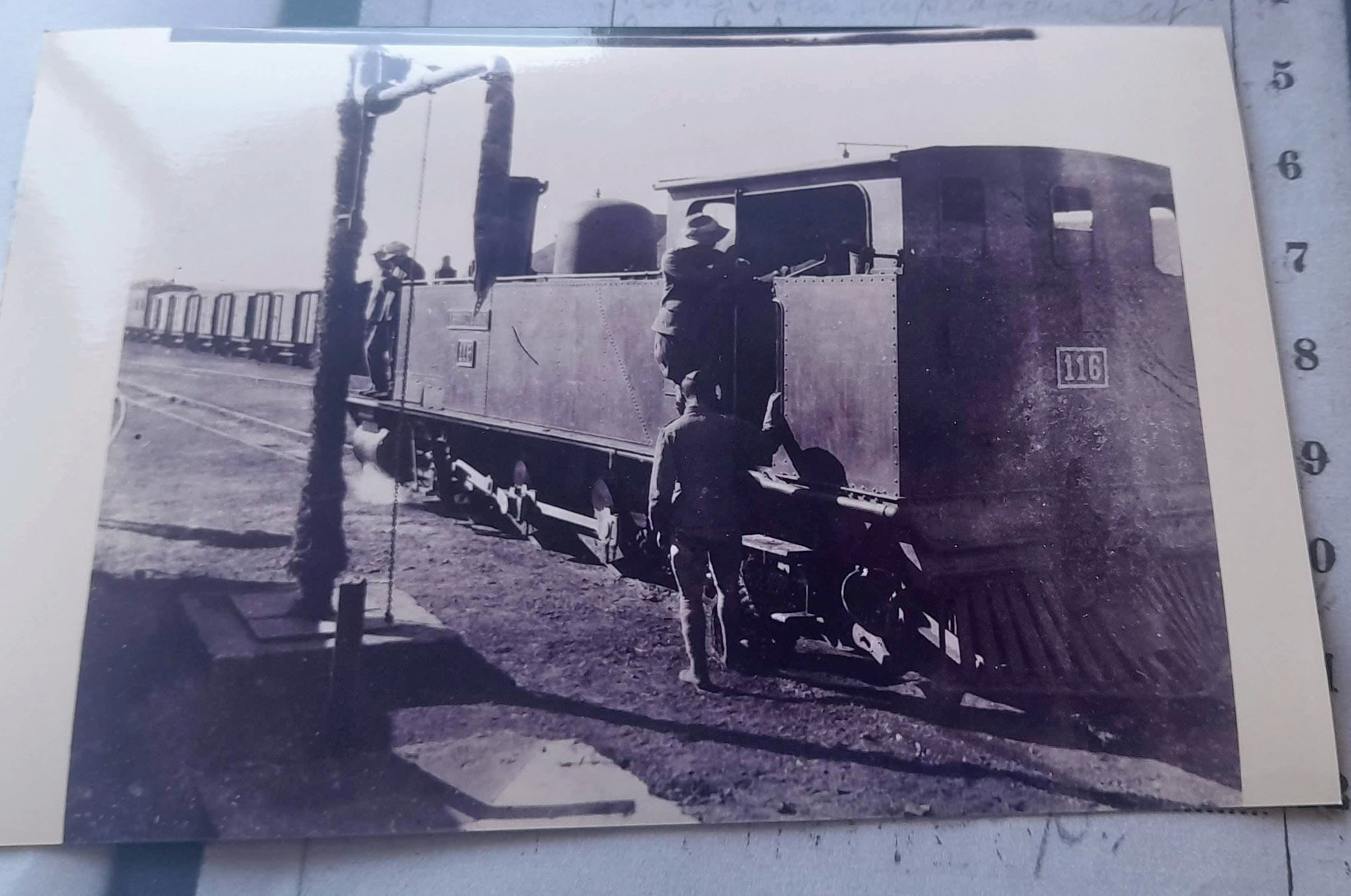

Luci Ellin and the children stayed in Durban for the duration of the war, while Fred worked on railway lines around the battlefields of Ladysmith.

The family returned to England several months after the peace treaty in 1902. Joanne remembers a pair of pottery watering cans, kept by her grandmother on the mantelpieces, brought back by the family from South Africa - a material legacy of the war and its upheavals.

“She just took the two kids, and she went down to London and boarded a ship at Tilbury Dock for Africa."

- Joanne Spina

Fred’s military career didn't end there. Joanne tells me - and Ministry of Defence files, declassified in 2018, confirm - that he later served in one of the British Army’s first experimental tank regiments, during the First World War.

She said: “He was told at first he was going to be joining the water tank regiment - and all the troops were told you weren’t to tell anybody, not your wife, not your kids, not your family, about this.”

Many of these military pioneers suffered from cordite poisoning, a common hazard in the poorly-ventilated prototypes. Joanne told me: “A lot of them would get out of the tank, they’d collapse on the floor like raving lunatics, and they’d actually start firing at the tank.”

She suspects this poisoning likely contributed to Fred's tragic death from throat cancer, at a relatively young age.

The Plaques

Hidden in the shadow of the York and Lancaster Memorial in Weston Park, a little to its left, is a bronze plaque.

It marks the memory of the 105 regular soldiers of the regiment - the majority from Sheffield or the surrounding cities and towns - who died in the course of the South African War.

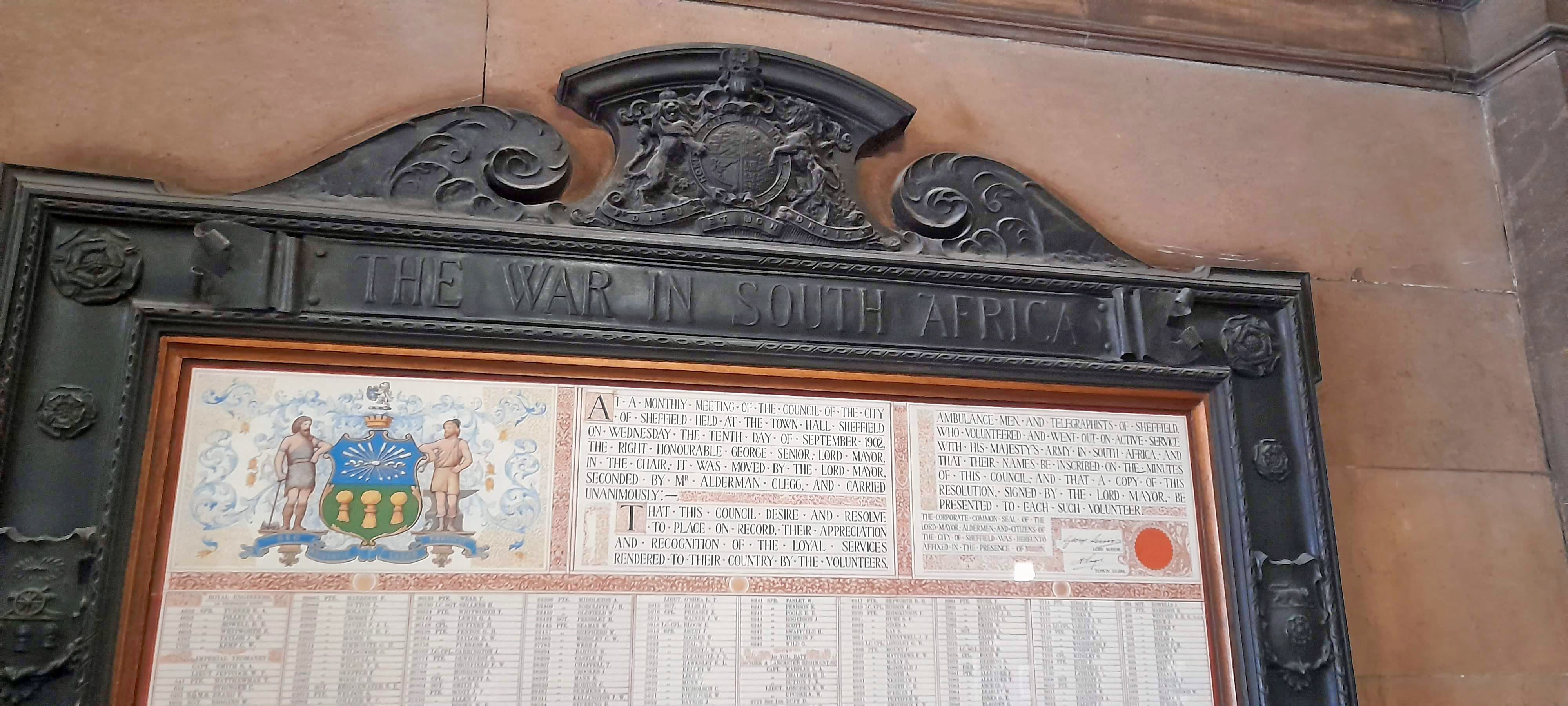

A second plaque stands in the foyer of the Town Hall, and tells an equally interesting story. This is dedicated to the 401 volunteers from Sheffield, who abandoned their civilian lives to fight for the Empire, almost 6,000 miles from home.

Who were these men? A breakdown of the regiments these Sheffield volunteers served in can shed a little further light. The majority volunteered as military engineers, across a wide range of units, including the Royal Engineers and all-volunteer battalions attached to the York & Lancs. Regiment. South Yorkshiremen also served in the Imperial Yeomanry, a volunteer cavalry force raised in 1900 to counter Boer commandos, while many also volunteered for the St. John Ambulance Brigade.

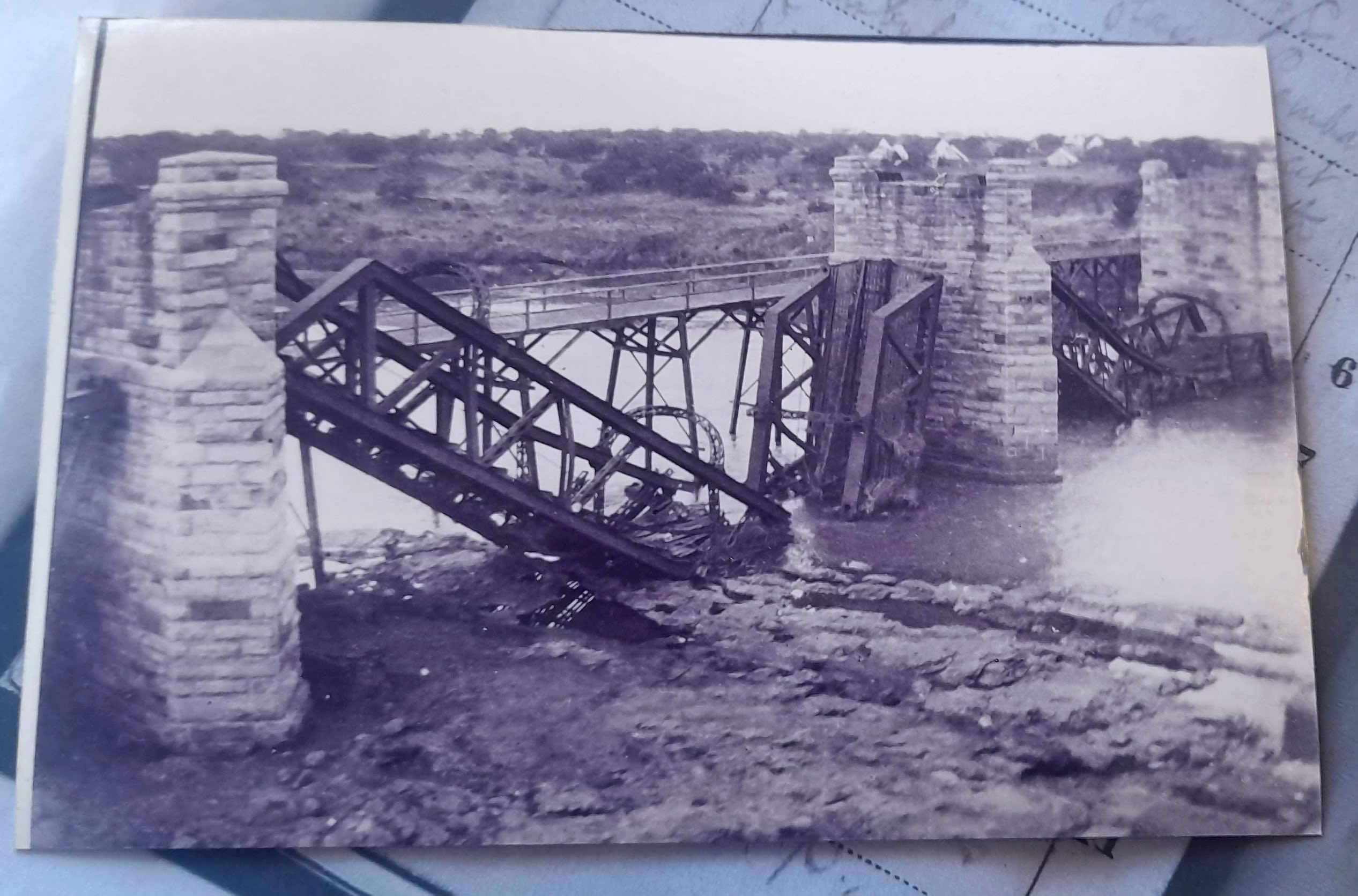

In an industrial city with a tradition of independent artisans, many Sheffielders had metalworking and engineering skills that were in high demand - to build and maintain the railways, telegraph lines, and defensive fortifications on which British counter-offensives relied. Most were deployed to Natal Colony, where the fighting was fiercest, and where supplies had to be taken from the port city of Durban over arduous distances inland.

War and Industry

An interview with Sheffield citizen Colin Barnsley on the experiences of his great-grandfather, Major George Barnsley.

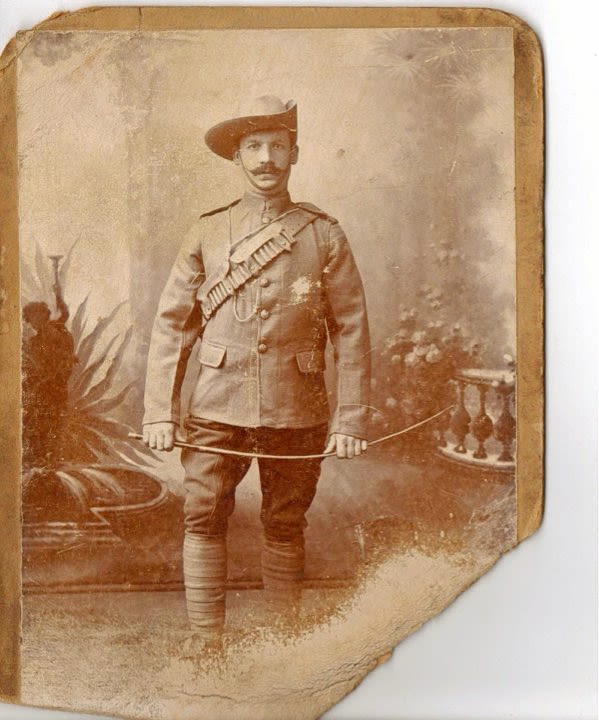

The careers of other Sheffielders also reflect this relationship between the engineering industry and military voluntarism - and future service in the Great War.

Colin Barnsley, former city councillor and amateur historian, told me his great-grandfather’s military experience stemmed from his management career in the venerable family tool-manufacturing firm George Barnsley & Sons.

Major George Barnsley commanded the 1st volunteer battalion of the West Yorks. Royal Engineers, throughout back-breaking engineering work during the final relief of Ladysmith.

Colin - who co-wrote a book on George, Forging History, with local historian Pauline Bell - suggested that officers and enlisted men alike would have picked up technical skills and adaptability from their industrial careers. He compared it to his own time at George Barnsley & Sons, saying: “My daily life with the family company was that a problem would come up and we’d have to find our way around it.”

He noted that the legacy of these same industries remains strong, telling me: “There’s still an immense amount of technical knowledge in Sheffield today.”

Politics and Memory

Beyond these individual stories, fallout from the war impacted Sheffield in a multitude of ways. The deplorable physical condition of many British recruits sparked healthcare reform by the Liberal governments of the 1900s, including school medical inspections, first rolled out at Hillsborough School in 1907.

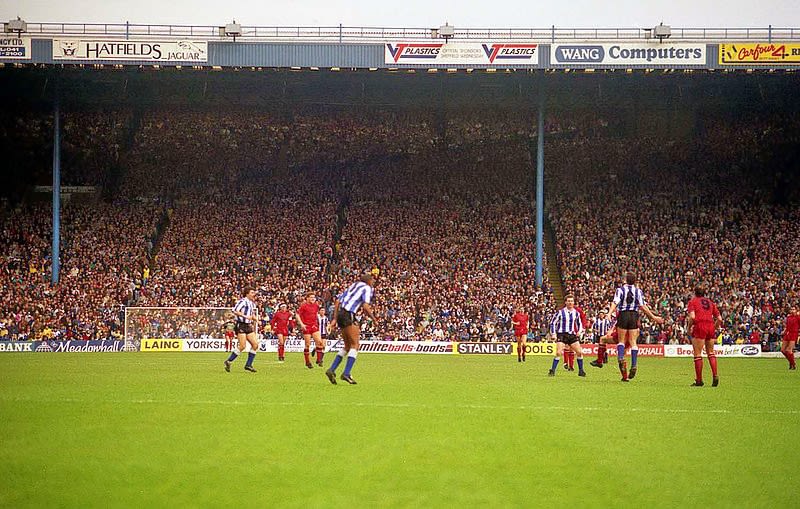

Place names like Ladysmith Avenue, in Nether Edge, and the Spion Kop stand at Hillsborough Stadium - named for a hilltop where the British suffered a stiff defeat - further testify to the widespread influence of a war that few remember today.

The war also had a stark impact on domestic politics in Sheffield. The conflict provoked strong feelings; anti-war meetings at the Attercliffe Vestry Hall were disrupted by patriotic vigilantes.

Fred Maddison, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield Brightside, lost his seat in the 1900 ‘khaki’ election, on account of his alleged ‘pro-Boer’ views.

______________________

Content by Shorthand. All graphics credited to author.

Photo credits to Daniel Thomas, Colin Barnsley, Fiona Jackson & Joanne Spina.