“We are robbing girls of the joy of sports”

Why shame, judgement and little resources make more than half of our 'sporty' girls quit.

When her teacher asked "what do you want to be when you grow up?" Emily Head knew. At just ten years old, she wanted to be a professional footballer. After waiting patiently while numerous boys announced Premiere League plans, Emily was shocked by her teacher's response.

"She told me being a professional footballer wasn’t a proper job for girls. After that, I lacked self-belief and felt judged."

Now a student, she hasn't stepped foot on the pitch since.

These are the everyday microaggressions that have led 55% of 'sporty' girls to drop out of sports, according to Women in Sport's 'Tackling Teen Disengagement in Sport' March 2022 report.

For the first time, the report revealed that girls are dropping out at a much higher rate than boys, with only 31% leaving sport behind. So why are girls disengaging and what can we do about it?

“It’s not that girls don’t like sports," says, Dr Jennifer Roberts, a gender and education researcher at the University of Edinburgh, "we’re making sports so they can’t like them."

Dr Jennifer Roberts, University of Edinburgh (Image from Jennifer)

Dr Jennifer Roberts, University of Edinburgh (Image from Jennifer)

“We’re robbing girls of the joy of sports. The majority would love to sweat and have fun but they don’t get to.”

Dr Roberts shares her journey with roller derby (clips from Canva)

Dr Roberts shares her journey with roller derby (clips from Canva)

According to the report, this is down to many issues such as judgement, confidence and puberty.

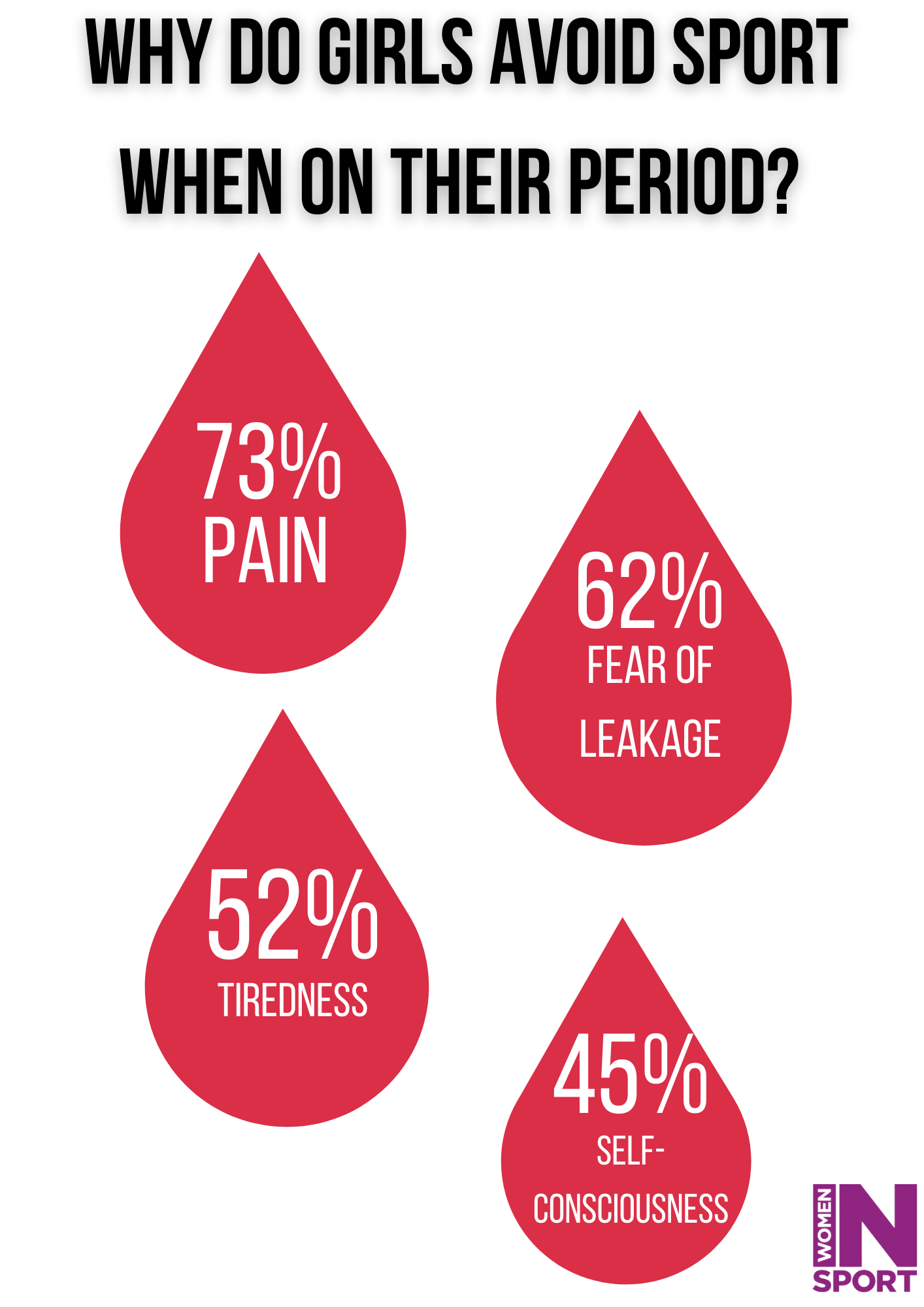

But by far one of the biggest obstacles girls face is menstruation, with 78% stating they avoid sports when on their periods. This often robs girls of a week of activity and leaves them at a disadvantage compared to their male teammates.

Although period pain influences this, fear of leakage and self-consciousness also lead women to avoid sport, says Dr Roberts: “we keep women out by making them afraid of their own blood.”

Even in contact sports like martial arts where blood is normalised, women are still ashamed of their periods. Rebecca Simpson, a 23-year-old Aikido enthusiast said:

“When I was younger, I didn’t train when I was on my period. I was mortified. Once, someone leaked on their trousers and they had to leave. Whereas a guy had a huge nosebleed which went on all over his clothes and he continued training. Both were blood but period blood was stigmatised.”

Rebecca has loved martial arts since she was 10.

Rebecca has loved martial arts since she was 10.

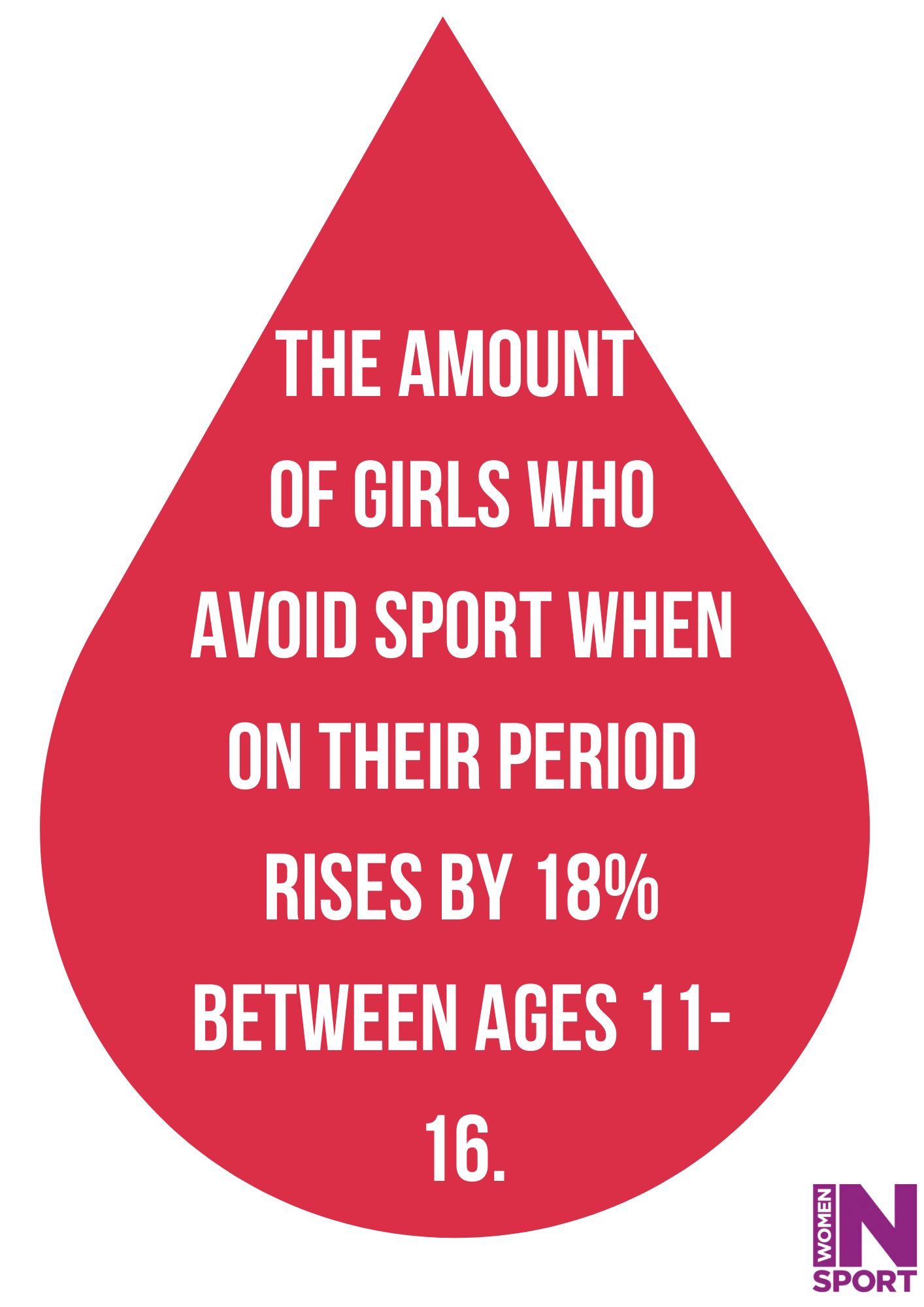

As girls grow up, the effect of this stigmatisation increases and 18% of 11-16 year old's avoid sport when on their period. (Women in Sport's Girls Active Survey)

Reframing Sport for Teenage Girls (2021)

Reframing Sport for Teenage Girls (2021)

Girls Active Survey (2017)

Girls Active Survey (2017)

But the barriers to participation begin well before puberty hits. In 2015, 'Tipping Point', a report by Women in Sport, found that by age seven, boys already think they are better at sports than girls. According to Dr Roberts, this isn’t entirely untrue:

“Boys have more opportunity to become sporty: more resources, time and training. In high school, the difference in their experience levels is too wide. Girls walk into P.E. disempowered so they step back. They think ‘I can’t win this game, so why am I going to play?’”

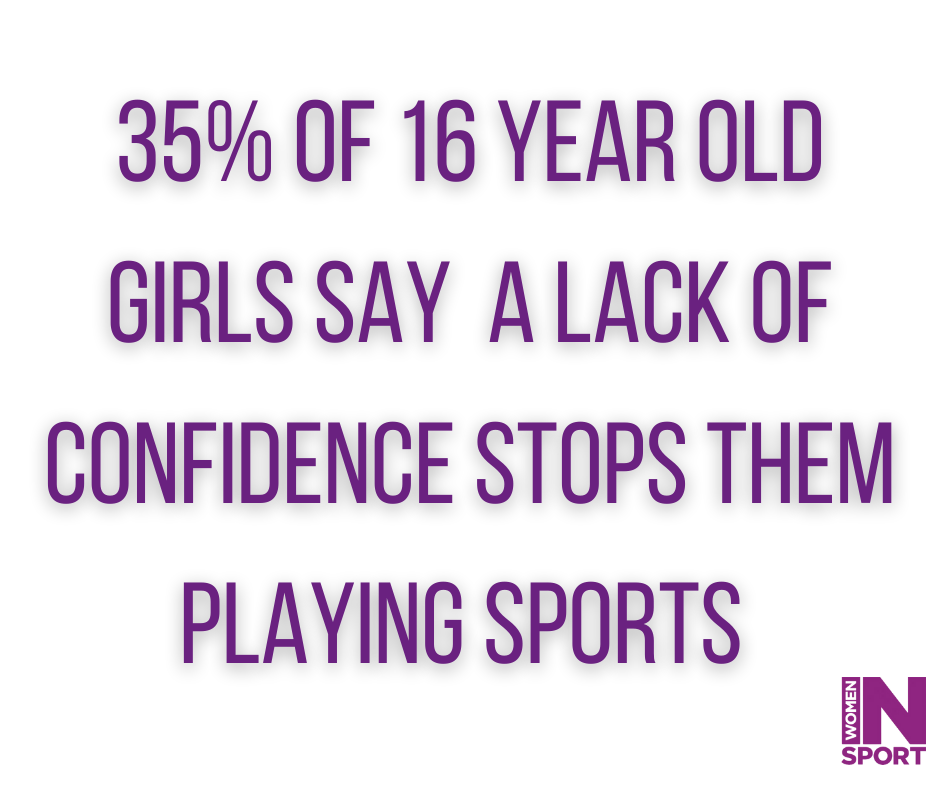

Therefore, while boys experience practical barriers like injuries, girls stop due to a lack of confidence and self-belief.

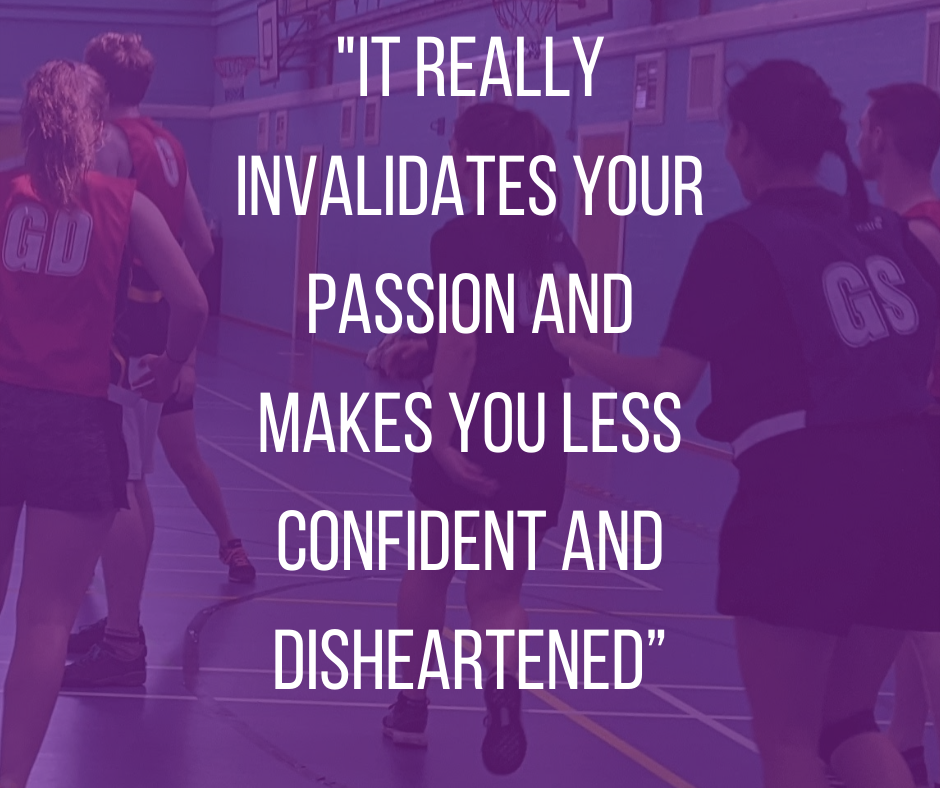

Even girls at the top of the game are invalidated and judged due to a disdain for women's sports, claims Dr Roberts:

“People think women’s sports aren’t real sports”

As Georgia, a 13-year-old netball player confessed: “I feel judged when boys say netball isn’t a real sport. It really invalidates your passion and makes you less confident and disheartened.”

Girls Active Survey (2017)

Girls Active Survey (2017)

Georgia, 13, plays netball at school.

Georgia, 13, plays netball at school.

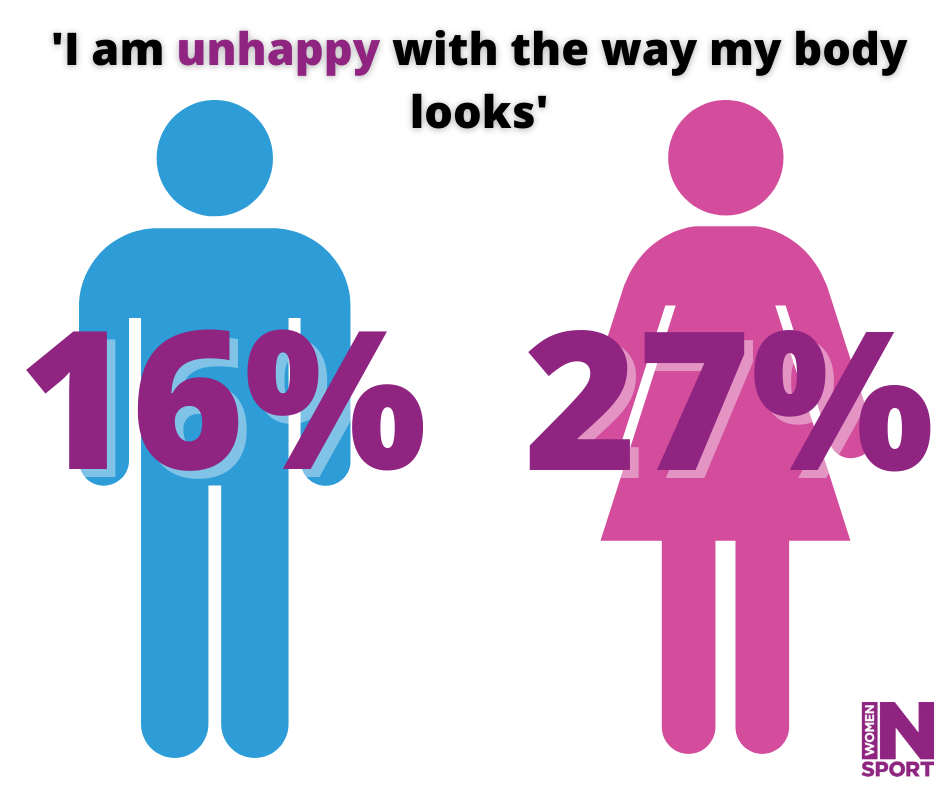

As well as their sport, girls also feel judged on their bodies. At a stage when girls already have low self-esteem, says Dr Roberts, P.E. is a ‘horrible’ experience where "girls are shamed, their bodies and abilities questioned.”

According to her, sportiness and attractiveness are at odds, meaning P.E. may exacerbate existing self-esteem issues: "If you become sporty, you can't be one of the cool, sexy, beautiful girls."

As Georgia,13, told us: “Young girls are over-sexualised and try hard to fit the standard to be pretty and popular. That sometimes means dropping out of sports”.

Even when girls participate, they feel pressured to look good. Grace Fidler, 21, describes her experience of climbing since the age of five:

“Women are more sexualised in sport and work out not for fun, but to make themselves look better.”

Many also fear potential changes in their appearance. Grace continued: “People often avoid sports because they might get big arms or legs.”

To even step onto the pitch is a battle for girls. They must tackle confidence issues, sexism and judgement, so encouraging girls to participate is no small feat.

In an attempt to do this, Sport England has invested £1.5 million in Studio You, an online library of activities available to all schools.

But Dr Roberts, ‘‘no solution would be as bad as that solution. Instead of making sports more equitable and accessible, we're saying ‘take this video and go home. Out of sight, out of mind.’”

The Department for Education has also awarded £980k to a sports leaders programme where girls teach will each other competitive sports.

A spokesperson said: “The programme will give thousands of girls access to sport opportunities.”

Again, Dr Roberts disagrees: “athletes with training are often used to support teachers rather than allowing them to compete and improve.”

Instead, experts have advocated for more variety alongside better investment, support and visibility of women's sports.

P.E. Teacher and personal trainer Gemma Spackman said: "It's media and money. Girls need to see themselves represented and to have more support at a grassroots level."

Thankfully, support for professional women's sports has increased by 21% according to recent data from Sky Sports. But whilst women's sports are growing at a professional level, more money and support is needed from the Government, teachers, coaches and parents to encourage children to keep engaging in sports throughout childhood.

Data from Women in Sport. (Tackling Teen Disengagement, Girls Active, Tipping Point)

Infographics created in Canva. Photos sourced from the author and interviewees.

Women in Sport, Girls Active Survey (2017)

Women in Sport, Girls Active Survey (2017)

Grace has been a climber since the age of five. (Image from Grace)

Grace has been a climber since the age of five. (Image from Grace)