We Are Igbo

We are Children of the Diaspora. We are living in the UK.

We are reconnecting with our Igbo Nigerian culture. Yes, we are Igbo

By Paula Ugochukwu

My Story

I am British Nigerian. Which for me means, I am born and raised in England but I am of Nigerian heritage because that is where my parents are from. Finding my own cultural identity has been a long journey because I have never felt British enough to be fully British or Nigerian enough to be fully Nigerian.

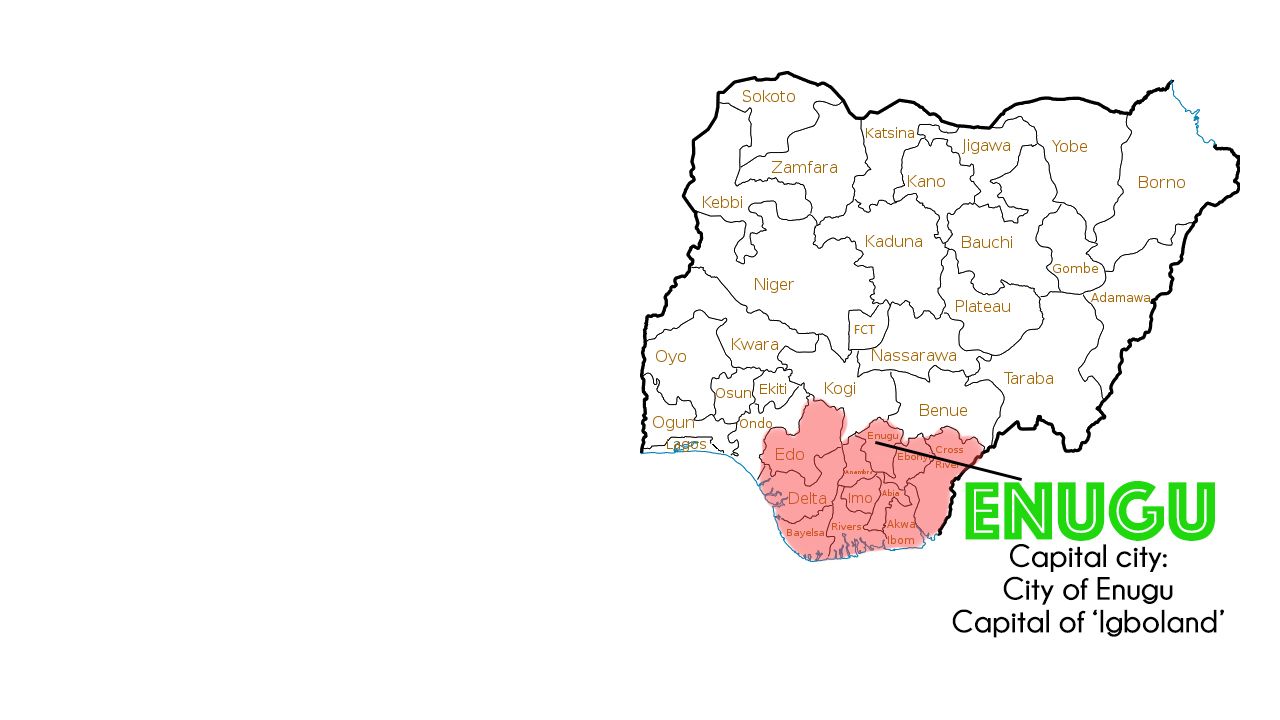

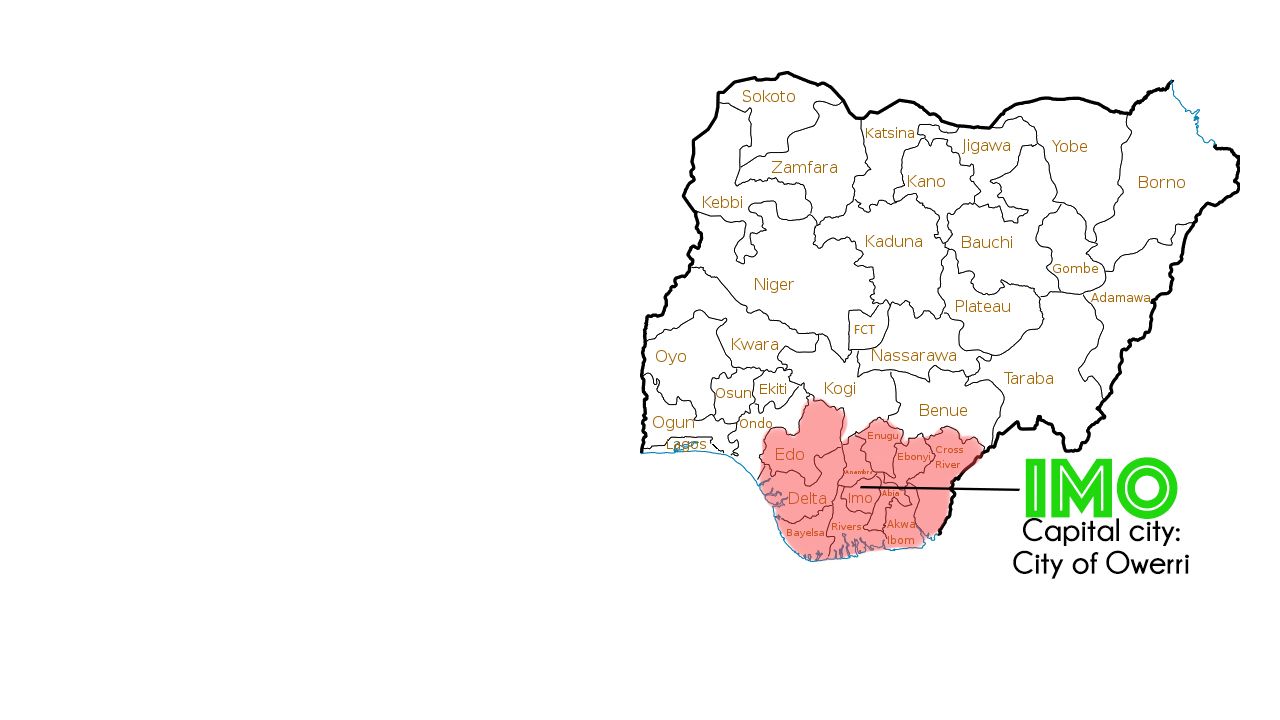

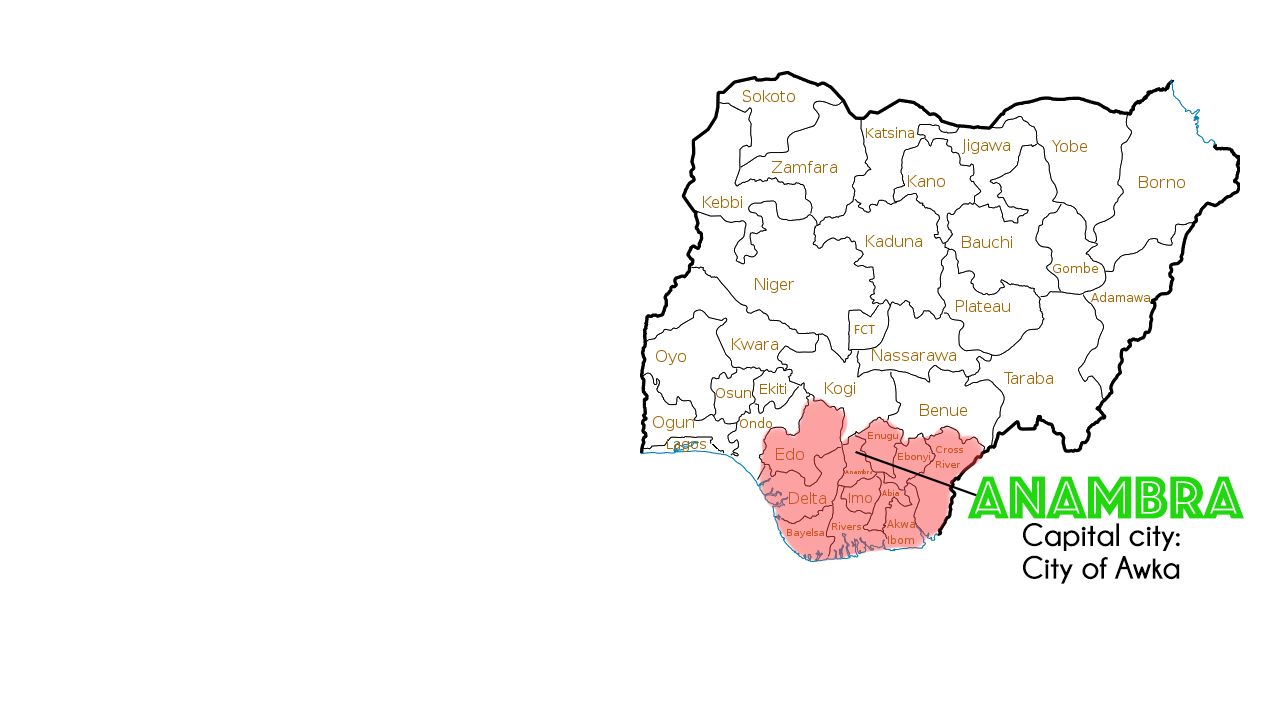

My parents were born and raised in Imo State in the south of Nigeria. After finishing university and getting married, my parents relocated to London where I was born one cold December morning in 1996. My first (and only) voyage to the Motherland was for a few months when I was three years old. My parents spoke only in English to my siblings and I, feeling it would be best if we had British accents and were fully assimilated in British culture.

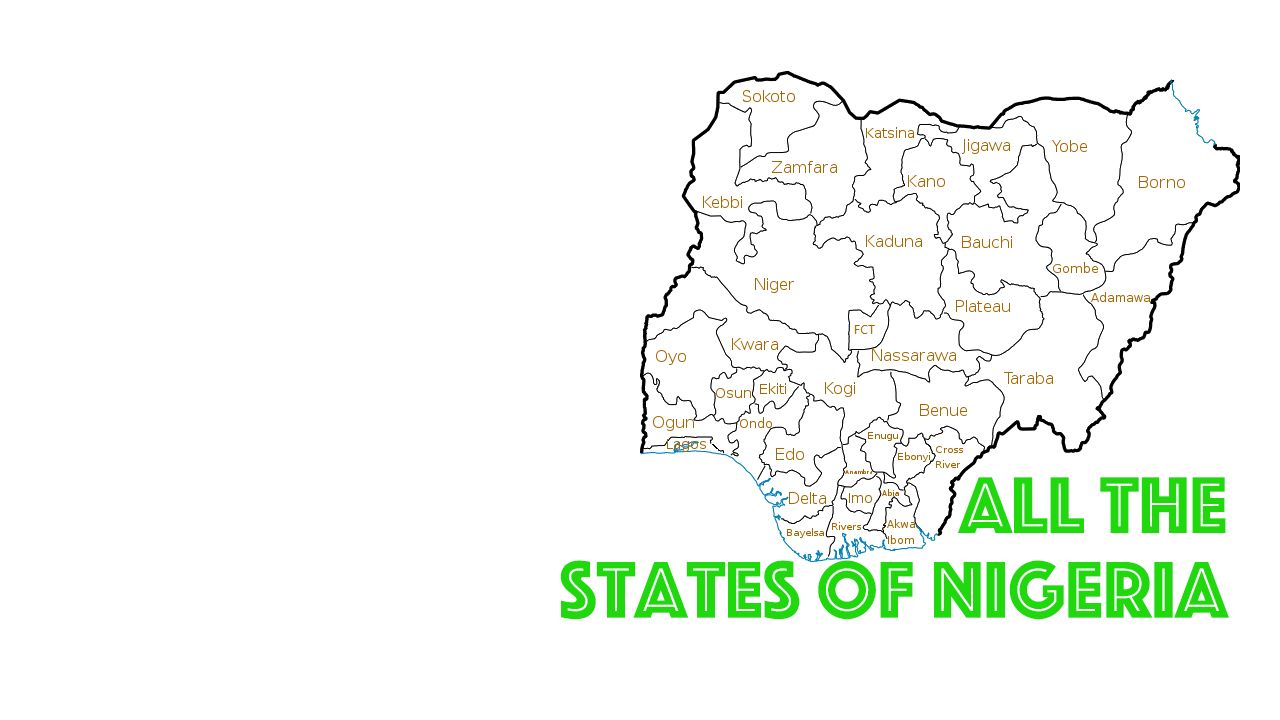

Nigeria has the largest population in Africa and is an economic giant, trading in oil and natural gas. But Nigeria - the West African powerhouse of a country that we know it as now - was initially a kingdom, home to hundreds of different indigenous tribes, all with different languages, cultures and religions. One of the largest three of these tribes was the Igbo (then known as the Ibo) people.

At the beginning of the 19th Century, during the rise of the British Empire, Nigeria was assembled together by the British. They implemented legal structures, Christianity and English as the national language, all of which undermined the traditional established ways of the tribes.

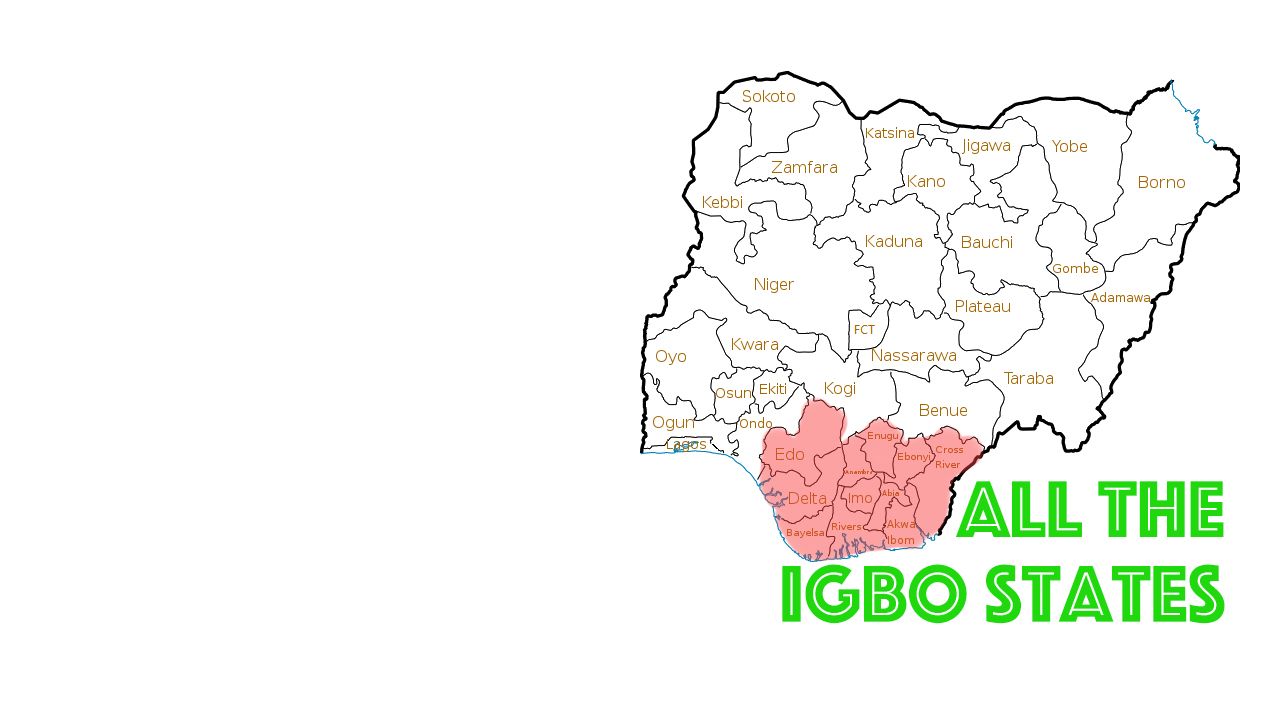

Nigeria got her independence from the British in 1960 but by then the way people thought, spoke and lived their lives were very different from before. Eventually the tireless struggle of people whose only similarity with each other was that they had been told they had to be a country, gave way. Between 1967 and 1970, there was a civil war that heavily involved the Igbo people. Those three years were a horrible time, for the whole country and especially for Igbos who saw an estimated 1-3 million of their people killed by warfare, starvation and disease. Many people were separated from family members and friends during this time.

There are two main points in history to account for Igbo migration to places outside of the Igbo states in Nigeria, nicknamed Igboland. One being the Transatlantic slave trade in the 18th and 19th century mainly to the United States of America and the other the migration of thousands after the Civil War and economic instability in Nigeria.

Now as an adult, when I have discussions with my parents about the Nigerian Civil War, they cry. It was a part of their history that they would prefer not to think about.

Even after the war, when peace had returned to Nigeria, the Igbo people seemed to have adopted a lot of the British ways of living. They are known for valuing religion highly, being dedicated to democracy and meritocracy.

I see these values in my parents, aunties and uncles. They love God and believe working hard means you will prosper in everything you do. Part of that means believing in sacrificing things that are hindering you from being successful - and for a lot of Igbo people, especially those living outside of Nigeria, that means detaching themselves from their old traditions, religions and sometimes even language.

Growing up, the Igbo language was barely uttered in my house. We were rarely told stories of my parents childhood growing up in Nigeria. I did not know how to answer “So, where are you from?” properly because all I ever knew was London. When I entered my early twenties, I decided I had had enough of my internal conflict and restless cultural identity.

I decided I am British Nigerian and for me that means I should and will learn and value both my cultures as much as I can.

Igbo names have really powerful deep meanings behind them. My full name is Paula Chibuzo Chiamaka Ugochukwu.

It is really strange for Igbo parents to give their children names that do not seem to have a meaning or cannot be translated. This is because it is part of tradition to give children a name or middle names that are either a wish of prosperity, are specific to the locality of the family or refer to what the family are going through at the time of the child’s birth.

For example, the name Onyebuchi means ‘Who is greater than God?’ and may be given to a male child after a woman, who has struggled to have children, finally gets pregnant and gives birth.

Many Igbo names are whole phrases or sentences made into a name and because of this, they can be very long. Due to the modernisation and westernisation of the Igbo culture over time, many people are shortening their Igbo names by removing letters. This can make it difficult to translate the meaning behind the name later on.

Before Christianity became the main religion in Nigeria and specifically among Igbo people, Igbos were polytheistic and worshiped several gods. They would name their children after a powerful god they wanted to watch over their child, such as Amadioha, the god of thunder.

Igbo tradition and culture differentiates between the supreme deity, Chukwu and smaller personal gods inside each person, Chi. Many Igbo names include Chukwu or Chi depending on if the wish is calling up the supreme God or the child’s personal, guardian god.

My surname, Ugochukwu literally translates as God’s Eagle but refers to being the crown or glory of the supreme God.

Background images by Tundeosunmedia

Here are some words and phrases used to start a basic conversation with someone in Igbo.

Hi/hello - Ndewo

Welcome - Nno

How are you? - Kedu ka ị mere?

I am fine, thank you. - O dị mma, daalụ.

And you? - Gi kwenu?

What is your name? - Kedu aha/afa gi? / Gini aha/afa gi?

My name is … - Aha/Afa m bụ ...

How old are you? - Afọ ole ka ịdị?

I am … years old. - Adị m afọ ...

Where are you from? - Ebee ka i si?

I am from … - M esi ...

What do you do? - Kee ihe ị na-aru?

I work in a (place) … - M na-aru ...

British Nigerian Actress and Producer, Bunmi Adaeze Mojekwu, known for playing Mercy Olubunmi in BBC's Eastenders and Aunty Sunbo in Nigerian series Jenifa's Diary, is of both Igbo and another Nigerian tribe, Yoruba heritage.

British Nigerian actress Bunmi Mojekwu - Bunmi goes by her Igbo middle name, Adaeze, in this video.

There are a lot of people that are of mixed Igbo heritage - whether that be a parent from another Nigerian tribe, another African nation or another country. It has been noted that these people often subconsciously adopt their other culture above their Igbo culture.

The Igbo language is spoken by 44 million people worldwide. Most speakers live in the south eastern states in Nigeria, but many live all over Nigeria, West Africa and across the globe.

Outside of English, which is the national language of Nigeria, Igbo, Yoruba and Hausa are the three main languages spoken, written and taught in Nigerian schools.

Igbo is known to be difficult to learn because there are over 20 dialects (regional variations in spelling and pronunciations) within the language. A centralised form of Igbo was formed in 1972.

Another important fact about the Igbo language is that it is very tonal. The pronunciation of a word, how nasally the sound is or the emphasis on a particular letter in a word, all can affect the meaning of the word.

For example, the word atọ means three but the word ato means basket. Did you notice the little dot underneath the O in the first ato? That changes how it is pronounced and also what it means.

*Note: green-white-green is the flag of Nigeria

Please - Biko

Thank you - Daalụ

Sorry - Ndo

Good morning - Ibọlachi/Ụtụtụ ọma

Goodbye/good night - Ka ọ di/Ka chi foo

Do you speak Igbo? - Ị na-asụ Igbo?

A little bit - Obele/Obere

Say it again please - Kwuo ya ọzọ, biko

Speak slowly - Kwuo ya nwoyo

No problem! - Nsogbu adighi

Yes - Ee/Oo

No - Mba