Welsh culture will suffer if farms are lost to mass tree planting initiatives

Wales has a wetter climate than the rest of the UK. This, coupled with its hilly terrain, means most of its agriculture is livestock based – sheep outnumber the people by three to one. As a result, 80% of the land is used for farming. This inevitably means that farming is a vastly integrated part of the Welsh culture, and any threats to this are taken personally by those living in the devolved country.

Worries over food security are rampant following increasing reports of farmland bought up by companies, charities and even the government for tree planting. However, food production isn't the sole role of farms in Wales. They're also a stronghold of the rapidly declining Welsh language, a pillar of local communities, and some have passed from parent to child for generations.

If the number of farms in Wales goes down, this threatens the future of Wales's heritage and culture.

The Language

Welsh is the oldest language in Britain and has spent 4,000 years evolving. In its earliest form, it was initially spoken throughout Britain before the arrival of English-speaking invaders in the sixth century.

Although the Tudors had Welsh roots, during their reign, Wales was somewhat absorbed into the English way of things and began to lose its traditions, and from that point, the language suffered a steady decline.

The current Welsh Government is trying to combat this with the introduction of 'Cymraeg 2050: Welsh language strategy' in 2017 to rebuild the number of Welsh speakers.

Nearly half of all working farmers in Wales speak Welsh on a regular basis, with this figure rising in the North and West.

The connection between the Welsh language and the agricultural sector is recognised, with the 'Iaith y Pridd' ('Language of the Land') report, published by Farming Connect, highlighting this.

"The findings of the 'Language of the Land' study suggest that the relationship between the various factors – both positive and threatening – which face the agricultural industry, rural Wales and the Welsh language overlap to such an extent that there is no point, nor is it possible, to separate one from the other – in protecting and expanding an individual factor, the other will also benefit, but by threatening an individual factor, they will all lose out."

Farming and language are interlinked, so if farms decline, it is likely the language will too.

Mark Morgan, a farmer on the Black Mountains, agrees: "This is a really big risk in Wales as a result of losing smaller family farms. Half a dozen family farms are the rural community in many parts of Mid-Wales."

"It's not just that they're a part of the community. They are the community in many cases. They're what is keeping the traditions and the language alive in many of these very rural places. Even in the less rural places, they still form a huge part of the communities."

Fraser McAuley, from the Country Land and Business Association, says that this connection might be one of the reasons farmers are so concerned about reports of land grabbing: "North Wales, in particular, is a real stronghold of Welsh language, like with West Pembrokeshire. Even places that aren't strong Welsh speaking are still quite proud of their farming heritage.

"If you read reports about farmers being offered lots of money, then it would be concerning, especially with all the issues they're facing at the moment."

(MS) Cefin Campbell says he's seen first-hand the impact on language that can come from losing farmland: "The four farms that are on sale in my area are up for sale because, sadly, there's no succession. They've retired, or one suddenly passed away three weeks ago with a brain aneurysm. There are no children to succeed them, so they sell the farm. It happens."

"All of them were Welsh speakers, and all of them contributed tremendously to our local community."

"When they were younger, they kept the young farmers club going. They always attended any events we have on in the community. Sadly, when farmers move away or die, then my fear is that we won't have Welsh speakers buying up those farms, not for that price. So, we lose four Welsh-speaking families in the community."

"It does make a huge difference to the language of where I live, and I would argue that it's the same everywhere in Wales."

Jon Parker, a farmer from Aberystwyth that is the Wales Director for the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission, wants any changes in Wales to be monitored so that the impact of farmland being used for tree projects can be recorded.

Credit: Jon Parker

Credit: Jon Parker

He says: "It's effectively private actors or charities that are coming into the mix in terms of land purchasing."

"There is a policy of a million Welsh speakers by 2050. If you have this policy, you need to monitor closely the impacts of change in rural Wales."

Credit: Mark Morgan

Credit: Mark Morgan

The Pembrokeshire Coastal Path, near Fishguard

The Pembrokeshire Coastal Path, near Fishguard

West Pembrokeshire is a stronghold of the Welsh language and has a large farming community.

Credit: Plaid Cymru

Credit: Plaid Cymru

MS Cefin Campbell says Welsh speakers are big contributors to his community.

The Preseli Hills

The Preseli Hills

In rural areas, farms form a huge part of the community.

This policy, announced by the Senedd in 2017, looks to double the number of Welsh speakers in the country.

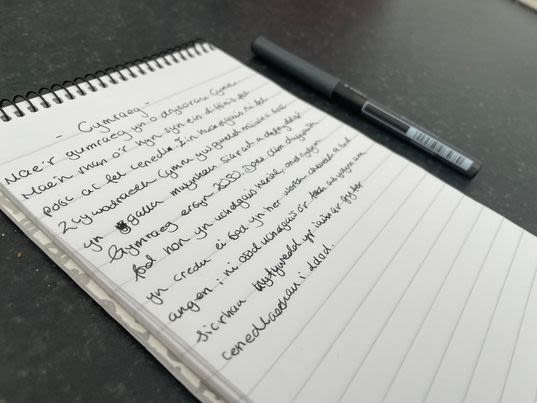

‘Cymraeg 2050: Welsh language strategy’

Credit: Senedd Cymru

Credit: Senedd Cymru

Jeremy Miles is the Minister for Education and the Welsh Language

The 2021 Annual Population Survey showed only 14.8% (448,400) of people speak Welsh on a daily basis, and 70% of people can't speak Welsh at all.

On 12 July, it was announced by the Minister for Education and Welsh Language, Jeremy Miles, that 23 new Welsh medium schools would be created across Wales.

Plans were also revealed to increase the capacity of 25 existing Welsh medium primary schools.

However, nearly half of all Welsh-speaking workers are farmers. If the number of farms in Wales declines, this will likely have a knock-on effect on the language, slowing down the goal of a million Welsh speakers even if more Welsh medium schools are created.

Jon says: "We've got to ensure that we properly monitor this, that we don't research it looking back. We need a real-time approach to monitoring the impact of how change is taking place. We need a closer eye on the impact across Wales in terms of land use and the changes to heritage, culture and language."

If the number of farms in Wales declines, this will likely have a knock-on effect to the language, slowing down the goal of a million Welsh speakers even if more Welsh medium schools are created.

Generational Pride

Farming in Wales is dominated by over 60s, and when they retire, there are concerns over the language eroding. This is likely to be accelerated as more farms are bought up for tree planting. But many of these farms have been in the same family for generations.

Fraser describes this struggle for farmers: "When a farmer reaches retirement age, selling up probably suits them, especially if there's no successor. But at the same time, there are quite a lot of farmers that have owned it, or their families have run it for many generations. "

"There's quite a lot of pride, and rightly so. There is a lot of heritage contained within our farms. "

"So many farmers don't really want to be the one that sells the farm that's been in the family for generations - that people have worked on their entire lives."

Jon says that the struggle to buy affordable land in Wales is affecting family farmers that already have their own land: "Many purchases of land for farming are attached to generational enterprises. So it might be that farms want to expand so they can have mum and dad and a son or daughter all being able to farm and maintain a living from a holding.

"They do this by increasing the size or diversifying the type of farming that they're doing by increasing in size, and the competition in the marketplaces from the government and companies is potentially stopping that."

Credit: CLA

Credit: CLA

Fraser leads the CLA's policy development in Wales.

Credit: Jon Parker

Credit: Jon Parker

Jon is a farmer and the Welsh director for the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission.

The Future for Young Farmers

As a young couple, trying to buy a small farm is acctually impossible. 12 months of looking, our house is officially sold and going to be homeless by Christmas at this rate 😫 Anybody know of a nice farmer that wants to help us out? Outbidded again today 😭 #nextgeneration

— Dr Bethan Eluned Till (@bet_till) October 29, 2020

The land struggle also presents problems for young people who want their start in agriculture.

Cefin says that buying land is too unaffordable for young people at present: "The cheapest farm of the four by me is for sale for £1.7 billion. Young people wanting to get into farming just can't contemplate paying that money.

"What I'm afraid of is that it'll be sold off in small blocks, destroying the farm unit. Or it'll get bought up by a company or for plantation.

"Do young people want to get into farming? Yes, a lot do. But a lot have seen at home the pressures that farmers face. It's not an easy life. It's long hours. It's a commitment 24/7. There's a lot of uncertainty at the moment around food prices, the cost of fertiliser and diesel, and the cost of animal food. It's all gone up about 40%, farmers tell me.

"They've seen all of this turmoil around, and they're thinking, 'come on, there must be an easier way of making a living than this.'"

Bob Davies is a farmer who worries his children won't be able to have the start in farming that he did.

"Buying land has never been easy. It's always been expensive, especially for youngsters. The traditional way used to be to rent the farms. Well, there's no one renting farms anymore. People are just cutting out and selling them straight for planting now.

"We know it is going to affect the future and the number of youngers that get into farming. The just isn't going to be the opportunities to farm because the land isn't going to be there to farm."

Bob and his wife bought their farm ten years ago but says he doesn't think the same opportunities are there now: "We couldn't buy it now, we wouldn't have a chance. We would just be outbid by the Foresight group, or somebody would buy it for trees now.

"Like I say to my wife, our children probably won't have their start in farming, as we're hoping they will."

"I'm all for increasing trees on farms, but what we see around here is not increasing trees on farms. It's increasing farms under trees."

"How can you compete with people that will pay 50% more for the land and farm? We just can't compete with them."

Farmers already face challenges to their industry, between reliance on food imports, low income and now the cost of living crisis. Adding to that now is the prospect of tree planting schemes overrunning their land and threatening their community. Most farmers aren't against tree planting, and contrary to the widespread media narrative many are willing to incorporate trees into their land. But they're scared that the problems they face are being ignored and Wales will suffer as a result.

The threat to the future of Welsh family farms is not going completely unnoticed, with an inquiry into the impact of climate change policy on the farms being launched by the Welsh affairs committee. However, more data is needed so that the full scale of the issue can be seen and the impacts on Wales can be monitored. Until then, the threat remains.