'Why We Fight'

An inside look at how thousands of Hongkongers are refusing to give up on their beloved city, even though they are living on the other side of the world.

It is lunchtime in London. Andy Teo craves for dim sum- like how he used to enjoy at one of the busy eateries in Sham Shui Po District.

The thought of feasting on piping hot steamed pork buns and shrimp dumplings while sweating away in the humid Hong Kong summer makes him salivate.

“Of course, there’s Chinatown here. But the feeling is just different,” says Andy, “the dim sum is so overpriced and not legit."

For someone who has been away for the last five years, it is perfectly reasonable to assume that Andy misses Hong Kong. But as the current political unrest unfolds, the 23-year-old university student insists that not even his love for Hong Kong food can convince him to return home.

“Look at what happened to Simon Cheng. He was arrested and tortured by the police when he went back,” he says, “I don’t want to go back to a place where I will get into trouble for speaking my mind.”

“Hong Kong is a dying city.”

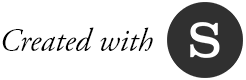

Photo taken by K.rol2007 from Flickr.

Photo taken by K.rol2007 from Flickr.

Andy is at Parliament Square.

He is joined by two thousand like-minded individuals ready to make their voices heard 9000km away from home. Surrounded by statues of some of the world’s greatest political revolutionaries, the likes of Nelson Mandela and Abraham Lincoln, it is the perfect starting point for an anti-government rally and march.

Most of the protesters are in black with a choice of face accessory - A gas mask represents the police firing over 11,000 rounds of tear gas at demonstrators, or a face shield that symbolises the protesters’ claim that the government is suppressing their freedom of speech.

For the occasion, Andy is in a black sweater with a Guy Fawkes mask. It is a way for him to show solidarity with the Hongkongers who have been protesting for the past six months.

“I’m living and working here in the UK. But most of my friends back home are not that lucky,” he says, “there’s no way for them to escape the tyranny and suppression.”

“We must liberate Hong Kong. This is a political revolution of our time.”

The protest march in London is organised by groups “Stand with Hong Kong” and “Democracy for Hong Kong”.

Similar protests are taking place all over the world in countries such as the United States, South Korea and Australia.

The movement has gone global.

Andy Teo and other protesters at a #StandwithHongKong rally held on 23 November 2019 in London.

Protesters at a #StandwithHongKong rally held on 23 November 2019 in London.

Photos taken by Ching Shi Jie.

Photos taken by Ching Shi Jie.

"We must liberate Hong Kong. This is a political revolution of our time."

Over the last six months, the streets of Hong Kong have been engulfed by waves of violent clashes between anti-government protesters, the police and those with opposing political views.

The crisis, which cripples the economy and paralyses the transport system, was triggered in April by the Hong Kong government’s plans to allow extradition to mainland China.

They insist that the bill prevents the city from being a safe haven for criminals.

However, protesters fear that China will use the proposed change to target activists and journalists who are critical of the country’s legal system.

They are also wary that the bill emboldens the Chinese government to interfere with the city’s affairs.

Hong Kong, a former British colony, returned to China in 1997 under an agreement that the city would follow a “one country, two systems” principle.

This means that although Hong Kong is part of China, it has its own judiciary and separate legal system from the mainland, such as freedom of assembly and freedom of speech.

Known as the Basic Law, it expires in 2047.

On September 4, Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam announced she would withdraw the extradition bill. But protesters say they will not rest until the government meet their "five key demands".

Five demands, not one less: A motto that the protesters have adopted over the last six months.

Five demands, not one less: A motto that the protesters have adopted over the last six months.

There is a more underlying cause to the protests than simply just down to the extradition bill.

A majority of the people in Hong Kong are ethnic Chinese. But they do not see themselves as Chinese citizens.

“The younger the respondents, the less likely they feel proud of becoming a Chinese citizen, and also the more negative they are towards the Central Government’s policies on Hong Kong,” says the University of Hong Kong’s public opinion programme.

A protester with a Hong Kong colonial flag, a symbol of an identity crisis within society.

A protester with a Hong Kong colonial flag, a symbol of an identity crisis within society.

The identity crisis damages Hong Kong society.

As the once peaceful extradition bill protest reaches the point of no return, families and friends fall out over their support for either the pro-Beijing camp or the protest movement.

“My parents are really supportive that I’m participating in the protests here, but they are the minority,” says Andy, “I’ve friends who’re no longer on speaking terms with their parents.”

His friend, who wishes to be named as Brian, agrees.

“If my parents know that I’m here, they will disown me,” he says, “but even if they find out, I’ll continue to protest against the Chinese and the police for using brute force to kill off our basic values.”

“I’m fighting for my future.”

With no end in sight, there are fears that Beijing will send in the People's Liberation Army to quell the unrest, mirroring the crackdown at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

But military intervention is unlikely, according to Dr Jamie Coates, a lecturer at the University of Sheffield’s School of East Asian Studies.

“The Chinese Communist Party is trying to woo international stakeholders. A full-on military intervention in Hong Kong is unthinkable,” he says.

The official death toll is disputed. But it is reported that hundreds of people were killed after soldiers opened fire on student-led protests at Beijing's Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989.

The official death toll is disputed. But it is reported that hundreds of people were killed after soldiers opened fire on student-led protests at Beijing's Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989.

Dr Coates, who teaches postgraduates Politics and Governance in China, adds that while UK and US support to the pro-democracy protesters are largely symbolic, they remain crucial in pressuring the Hong Kong government. Change is essential in returning the city to normality.

Three hours into the march, Andy and the protesters have reached the finale.

Illuminating the night with their mobile phones, they begin singing “Glory to Hong Kong”, the movement’s protest anthem.

Fitting end to the march. Thanks to all who joined. And thank to @Stand_with_HK and @DemocracyforHK for organizing#StandWithHongKong #FightForFreedom pic.twitter.com/J9M9ctGurp

— HK Demonstrations In UK 😷 (@HK_Connect_UK) November 23, 2019

“If the situation gets better, maybe I’ll go back and have dim sum,” says Andy.

“London is where I live. Hong Kong is my home.”